Cynthia, left, and sister Christine, right, survived the bombs of the infamous Coventry Blitz (Image: Supplied)

November is always a month for remembrance but this time of year has particular poignancy for Cynthia Smith of Coventry. It’s her birthday month but Cynthia won’t be celebrating, because Cynthia, 87, was born on November 14, now marked as the anniversary of the infamous Coventry Blitz.

Between September 1940 and the summer of 1941, the German Luftwaffe unleashed a bombing campaign on Britain like nothing ever seen before. Over those months, more than 43,000 civilians lost their lives and an estimated three million homes were destroyed as Hitler attempted to cripple Britain’s industries and break British morale. Though London bore the brunt, cities up and down the nation, from Plymouth to Glasgow, suffered devastation too.

For the children who lived through the Blitz as it came to be known, these were days that would shape the rest of their lives. Now in their eighties and nineties, these members of the Silent Generation, still remember the sights, sounds and even the smells that defined their wartime childhoods.

Devastation in the centre of Coventry after the Luftwaffe’s aerial bombing campaign (Image: Getty Images)

In Coventry, on November 14th 1940, Cynthia had just blown out the candles on her second birthday cake when the sirens began to wail. Ordinarily, her mum Minnie would have taken Cynthia and Christine to wait out the air-raid in the cupboard beneath the stairs but guided by some divine providence, that night the little family bedded down in the communal shelter across the road. The air-raid, which the Germans called Moonlight Sonata, continued all night long. More than 500 bombers crossed the city, first from north to south, then east to west, targeting not only – as the British had expected – Coventry’s valuable factories, but her residential streets and historic centre too.

When Minnie carried her daughters out of the shelter the following morning, it was also a scene of utter devastation. The dust in the air made it dark, even at lunchtime. The house next door had taken a direct hit. “And all my birthday cards had been blown off the mantelpiece,” Cynthia says.

As the day progressed, the official death toll rose above 500, though it’s possible many more were unaccounted for. More than half the city’s homes were damaged. Of her medieval cathedral, only the tower remained. The Luftwaffe were so pleased with their terrible work that they coined a new verb – Coventrieren (to Coventrate) – to describe the act of razing a city to the ground.

From that day forward, Cynthia Smith’s childhood was utterly changed. She remembers walking with her mother through the devastated streets. “It was the smell that was the worst,” she says. “The smell will never leave me. Brick dust and burning. Like a candle that’s just been blown out. As soon as I think of the bombing, that smell is in my nose again.”

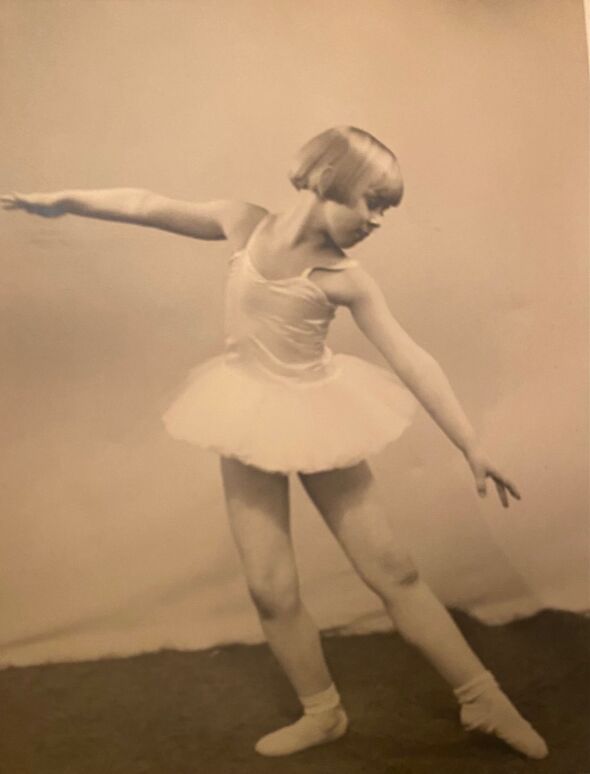

Jeanette had to navigate air raids and blackouts while attending the Royal Academy of Dancing in London (Image: Supplied)

In London, young Dot Clowry also faced the fury of the Luftwaffe. With her father away in the army, Dot, now 91, was living in Earlsfield with her mum and two little brothers, the smallest just a toddler. With three such small children to care for alone, Dot’s mum had come up with a routine. As soon as the children had had their tea, whether the sirens had gone off or not, they would be put to bed in an Anderson shelter in the garden behind their house.

Though it was cramped, it was cosy, lit only by candlelight. It wasn’t too frightening until the night a German bomber took out half the street. Dot’s family home was only half-destroyed but the rubble created as it tumbled down fell right over the garden shelter, trapping Dot, her little brothers and their mum inside. After the candles burned down, they found themselves in the pitch dark, not knowing when help would come.

“I don’t know how long it took them to find us but it felt like forever,” recalls Dot. “Sometimes we could hear voices nearby but they never seemed to get to us. We must have shouted when they got close but I suppose there were injured people outside on the street to be dealt with first. Perhaps they didn’t hear us and thought we were already dead.”

When Dot and her family were rescued, she raced outside to see their house open to the elements on one side. Despite this shock, her parents refused to see their children evacuated to the country. Though she maintains that, surrounded by the love of her family, “the war was quite a happy time for me”, Dot still suffers from claustrophobia and can’t sleep with the lights out at night.

In nearby Mitcham, Jeannette Tomlinson’s family slept in the communal shelter on Figge’s Marsh, which was often flooded. Later in the war, when Jeannette’s father was called up, leaving her mother to cope with two daughters and a newborn alone, Jeannette got an early taste of independence.

She had to learn something beyond being streetwise, as she navigated the dangers of the blackout and air raids, on her way to and from the prestigious Royal Academy of Dancing in Holland Park, where she had a scholarship. “There was always a chance you might not be coming home,” Jeannette says. “But though I was only 12, I wasn’t scared. Going on my own to those dance classes, I got to see a bit more of the world.” Jeannette’s dedication paid off and she became one of Clarkson Roses Rose Buds in the popular revue Twinkle, performing alongside Terry Scott (of Terry and June fame).

It was a time of fear but a time of strange excitement too. In Essex, Derek Hull, 91, recalls the thrill of watching Brentwood’s Ursuline Convent go up in flames. “We couldn’t take our eyes off it. We were all just saying to each other, ‘Cor, look at that!’” To Derek, then only seven years old, to see the huge fire was a novelty. It was only when the ARP warden hammered on the door and berated his mother for letting her children watch the conflagration from their bedroom window, that the danger of the situation sank in. The heat could cause the glass to shatter at any moment.

Jean, Robert and Derek Hull in 1940 (Image: Supplied)

Up in Yorkshire, Ann Hay, 88, knew of the dangers of broken glass. When a lone German Junkers Ju 88 dropped a bomb on the Majestic Hotel in Harrogate – the only bomb to fall on the town during the war – the windows in the dining room of Ann’s house, right opposite, were blown out. Sneaking up from the basement to see if the stewed apple she’d had to leave behind when the siren sounded was still on the dining table, Ann very nearly ended up with a mouthful of glass. The pudding she’d been longing for was full of dagger-sharp splinters. Her mother snatched it away from her just in time. “Eighty-five years later, I still can’t eat stewed apple,” she says.

In Wandsworth, Sylvia Lee, 86, was sitting at the top of the stairs with one of her brothers when the skylight above them was shattered by a bomb blast, covering her and her brother with glittering shards. Glancing up towards that self-same skylight, in the house where she still lives, Sylvia says, “I don’t know how we weren’t cut to pieces.”

Afterwards, her parents decided it was time for the children to be evacuated, though they didn’t stay long in the countryside, preferring to face the bombs together.

Though their childhoods were marked by war, the children of the Silent Generation are remarkably sanguine about their experiences.

And there were small moments of levity in the terrible time. Sylvia Lee’s husband, Tony, 88, grew up in nearby Battersea. He still chuckles as he recalls a night when his soldier father was home on leave. “The air-raid siren went off and we all trooped down to the shelter. Dad came with us. I went into the shelter straight away with Mum but Dad stayed in the entrance, watching the planes flying overhead. He just stood there, looking up, with his arms folded across his chest like the big ‘I am’. The air-raid warden was going spare, trying to get him to come inside. Then a bomb fell further down the street and the blast lifted Dad off his feet, planting him in the middle of the shelter on his backside. We all fell about laughing. The air-raid warden said, ‘I told you to come inside, Mr Lee’.”

Smiling at the memory of her father-in-law, Sylvia chimes in, “I hoped that people would learn from our experiences. But when you look at the news, with all the bloodshed going on all round the world, it really doesn’t feel like they have. Why can’t we all stop fighting?”

It’s a sentiment shared by Cynthia Smith, who finds her memories just as vivid today as they were when she was a child. Eighty-five years after the Coventry Blitz, Cynthia still can’t stand the smell of candles, saying, “My family was lucky. Others had it much, much worse. But Adolf Hitler ruined my birthday.”

War Babies by Chris Manby and Simon Robinson (Mirror Books, £9.99) is on sale now from all good bookshops and Amazon

War Babies by Chris Manby and Simon Robinson (Mirror Books, £9.99) is on sale now from all good bookshops and Amazon (Image: Supplied)