Slovakia commemorates the events of November ’89 each year largely on a symbolic level. Yet their real impact on living standards becomes clearest when comparing everyday life then and now.

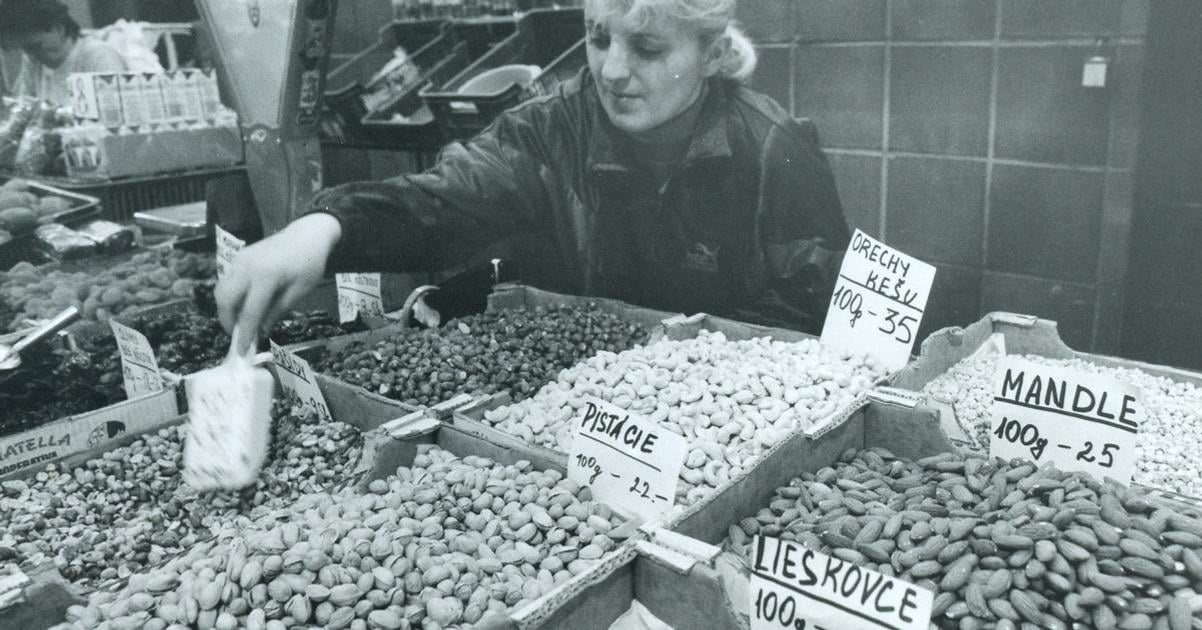

Before 1989, higher-quality goods could mostly be found in the so-called Tuzex shops, which operated using vouchers known as Bony. For ordinary people, these were accessible practically only through the illegal black market. Shortages were no accident; they were a direct result of political interventions in the economy. Quality of life gradually declined and public dissatisfaction deepened, compounded by restrictions on travel and freedom of expression, ČSOB analyst Marek Gábriš notes.

“Most citizens were equal mainly in their poverty,” Gábriš says as cited by the SITA newswire, adding that strict central planning, investment stagnation and the neglect of innovation pushed the economy by the late 1980s into a state where its lag behind Western economies was visible not only in statistics, but also on shop shelves.

A comparison of what a citizen could buy with one month’s wage in 1989 and today reveals striking differences. When it comes to basic foodstuffs, today’s options are far broader. The average wage now buys 190 litres more milk, thousands more eggs, hundreds of kilograms of rice and hundreds of packs of butter than before the revolution. Even beer, once a symbol of stable pricing, is more affordable at today’s wage levels. A single month’s pay now buys almost 275 more half-litre bottles than in ’89, noted Gábriš.

The biggest differences, however, are found in consumer goods. These were often out of reach for ordinary people and, if they appeared in shops at all, it was usually in very limited quantities. Today, one wage buys four times as many refrigerators as in 1989, three times as many children’s bicycles, and nearly 14 times as many televisions. Mobility has also improved significantly: one month’s pay now buys roughly three times as much petrol.

A striking symbol of improved affordability is the private car. Before the Velvet Revolution, buying one meant working for nearly 27 months – and even then, prospective owners had to add their name to a long waiting list. Today, an average worker can afford a car for less than 10 monthly wages, with virtually no wait at all.

The comparison highlights not only a rise in living standards, but also the profound impact of market liberalisation, the freer movement of capital and technology, and households’ ability to make independent spending decisions.

“The social changes after 1989 thus shaped not only political freedoms, but also everyday life – the quality of which is today, in many respects, incomparably higher,” Gábriš concludes.