In 1978, just a year after the Environmental Protection Agency began to ban PCBs, 30,000 gallons of oil containing the widely used chemical additives were secretly dumped in North Carolina. Or sprayed, rather: for three months, a pair of brothers drove during the night across 14 counties, spraying the side of the road with the oil.

It was a last-ditch solution to a failed scheme to corner the market for PCBs after their domestic production was banned. The illegal disposal of the chemicals was soon discovered, and North Carolina authorities had to figure out how to clean it all up. Their solution? Remove the dirt that was illegally contaminated with the carcinogenic chemicals and legally dump all 10,000 truckloads in a new landfill in Warren County, where the population was 60% percent Black.

RELATED: Trump’s EPA to Black People: No ‘Environmental Justice’ for You

The plan did not go over well with local Black residents, to say the very least.

There was a groundswell of organizing against the landfill, and in 1982, a host of civil rights leaders came to Warren County to bolster their efforts. One of them was Dr. Ben Chavis, a member of the Wilmington 10 who in 1971 had been wrongfully accused and convicted of fire bombing a white-owned grocery store. Eight years later, Chavis was freed from his 29-year sentence after the group’s prosecution was revealed to be a racist sham.

In Warren County, Chavis was arrested again, for allegedly driving too slowly on a county road. As he was put into a cell, he said something that crystallized what was at the root of the state’s PCB dumping plan, and the opposition that had risen up against it. “This is racism,” Dr. Chavis said. “This is environmental racism.”

RELATED: Fossil Fuels Are Poisoning Black America

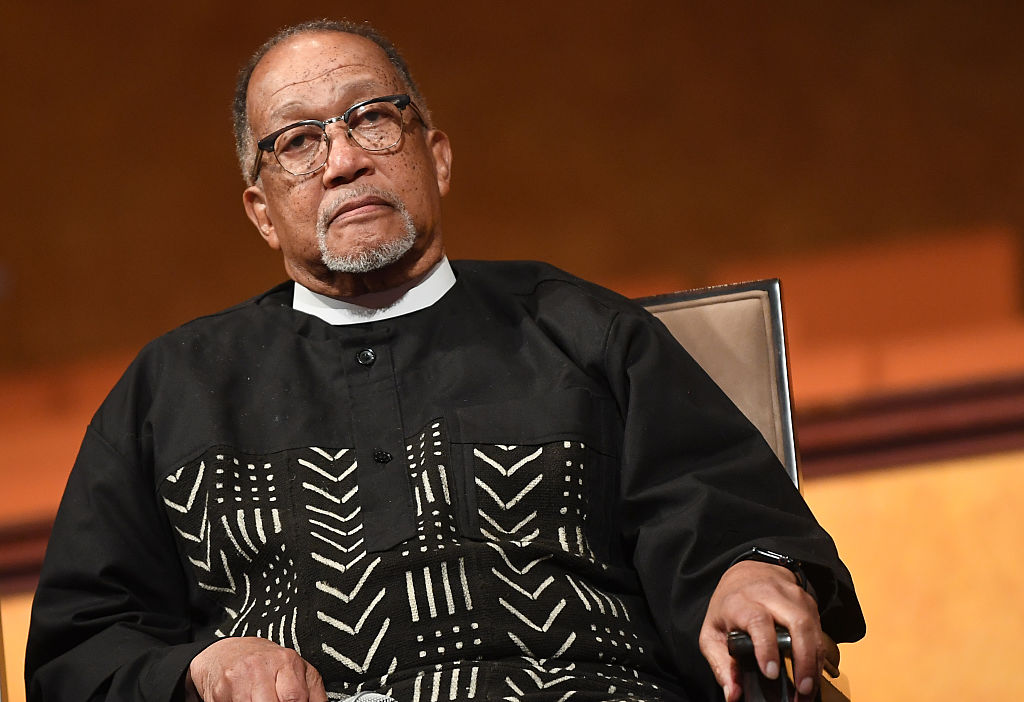

Late last month, Dr. Chavis, who is currently the president and CEO of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, was honored for his role in the environmental justice movement — which, in many ways, coalesced around both the Warren County protests and his words — at the Mississippi Statewide Environmental Climate Justice Summit.

While the Warren County protests ultimately failed to stop the landfill, they sparked a larger movement, inspiring both organizing around and research on this new idea of environmental racism.

“During the 1980s, you couldn’t make just an allegation of discrimination; you had to prove it. You had to statistically show that it existed,” Dr. Chavis said at the summit. “Nobody ever asked, was there a correlation between the proximity of toxic waste facilities, toxic emissions, and climate emissions to public health?”

In the wake of the Warren County protests, researchers did just that: “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States” was a groundbreaking report published in 1987. It found that “communities with greater minority percentages of the population are more likely to be the sites of commercial hazardous waste facilities.”

The author of the report, Charles Lee, was directly inspired by the protests in Warren County, which he had travelled from his home in New Jersey to take part in. After reading a study that showed 75% percent of landfills in the South were alongside Black communities, “I said, ‘We need to replicate this on a national scale,’” Lee told the Washington Post in 2020. The report was published by the United Church of Christ for Racial Justice, for which Dr. Chavis was the executive director at the time.

Environmental racism eventually gave way to environmental justice, and the movement has changed over the years to now account for climate justice, too. And the connection is not lost on Dr. Chavis, who has the international climate conference on his mind at the Mississippi event.

“To COP30: don’t cop out, cop in,” he said. “Cop in to lay the groundwork and the reaffirmation of a global struggle to prevent climate crisis, climate injustice, and to respond to the environmental injustices that are growing all over the world.”