I’ve been to some out-of-the-way places, including Haiti and Niger, neither of which receive much American tourist traffic. When I tell people about these travels, they generally express mild curiosity, along the lines of “Why would you go there?” Until this year, when I decided to go to Pakistan, to trek the Nangma Valley. When I mentioned that trip, the response was almost universal: “You should seriously reconsider going to such a dangerous place,” often followed by quips about beheadings and kidnappings.

This concern is shared by the U.S. State Department, which cautions that Pakistan suffers from terrorismandarmed conflict. The Department flatly advises against traveling to far southern and northern provinces, as well as areas immediately adjacent the India-Pakistan border. As a result of risks, perceived or real – and even though Pakistan has more than 108 peaks exceeding 23,000 feet, including K2, the second-highest mountain globally – each year less than 10,000 Americans journey to Pakistan. With more than 250 million inhabitants, it’s the world’s fifth most populated country. Roughly 700,000 visit Brazil, which has the seventh largest population.

As a Peace Corps trainee in Senegal and Fulbright Scholar in India, I view State Department advisories as recommendations as opposed to the final word on in-country conditions. Afterall, if the Department was assessing the United States, it might caution against visiting schools or political rallies as places with elevated shooting risks. Several years ago, my family hiked the Simien Mountains in Ethiopia even though the State Department encouraged Americans to avoid the region. Before getting on a plane, we talked to friends at the Department and at non-governmental organizations who frequently traveled to the country, all of whom said it was safe.

Following global patterns, glaciers in Pakistan, along the Nangma Valley, are steadily shrinking. Photo: Steven Moss

Following global patterns, glaciers in Pakistan, along the Nangma Valley, are steadily shrinking. Photo: Steven MossParts of Pakistan aren’t benign, including the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa region, which borders Afghanistan, where Taliban insurgents are active. The Nangma Valley is in the Gilgit-Baltistan province, about an hour flight from Islamabad, the country’s capital, an area tightly controlled by the national government. The trek, and the outfitter I chose, had been recommended by The New York Times. The chorus of cautions made me uneasy – and caused my wife, Debbie, low-level anxiety – but I ultimately decided to go, perhaps perversely drawn by the path less traveled. Also, I’m stubborn, a necessary trait to want to hike to high altitude in a remote location to celebrate my 65th birthday.

As soon as I disembarked in Islamabad, I felt comfortable. I was greeted by rose petals strewn on the airport’s exit corridors, remnants of welcome celebrations for Pakistanis returning home from Saudi Arabia. People were dressed in shalwar kameez – loose trousers and long tunics – the women wore simple head scarfs. It felt like a subdued version of India.

At museums, parks, and shops men often stopped and shook my hand, asked me where I was from; only occasionally narrowing their eyes in mild hostility when I said the United States. More frequently they invited me to their home, for a meal. It’s friendlier than most places I’ve been, more amiable than Europe. In villages children stopped, stared, and giggled, half hiding behind their mother’s legs.

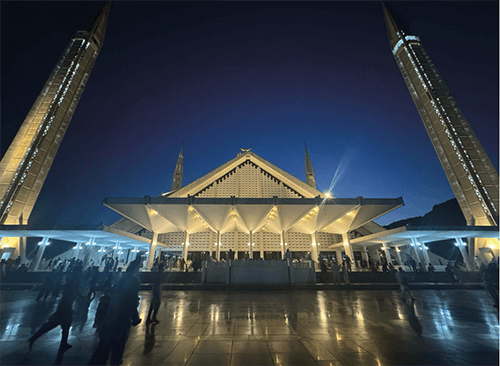

Faisal Mosque. Photo: Steven Moss

Faisal Mosque. Photo: Steven MossTouring Islamabad, I arrived at the mostly empty Faisal Mosque, the sixth largest in the world. I made my way to the minbar, a raised platform where services are delivered, to examine the qibla wall. Suddenly, a crowd of men appeared next to and behind me, standing in neat parallel rows, toeing lines woven into the carpet, hands folded in front of them. The man to my right, who was accompanied by an adolescent boy, smiled and shook my hand.

It was time for the after-sunset Maghrib prayer. Unable to leave without breaking through multiple lines, I looked to my left and copied the movements of my next-door neighbor, an older man. What seemed like recorded prayers streamed over loudspeakers, followed by the ticking of a clock, signaling different positions: standing while raising hands, bowing, prostrating, sitting. It was a kind of spiritual calisthenics. I was delighted to be a part of it.

I went on to successfully complete my trek. There were some scary moments – rickety wooden bridge crossings over raging rivers; thin, slippery trails adjacent to deep chasms; barefoot traverses on sharp rocks across cascading waterways – but none of them were related to people. Perhaps even more than negotiating steep slopes over rocky boulders at high altitude, the greatest accomplishment of my trip was being an American Jew praying peacefully, shoulder to shoulder with Pakistani Muslims. After which we all went home to our families.

Post navigation