Shabana Mahmood announced nearly 40 measures to reform the asylum system but many have raised more questions than answers.

A Home Office source said they had not worked out “any of the detail” and the measures announced were designed to show voters the direction of travel.

However, a source close to the home secretary said they offered “serious reform” and would “restore order at the border”.

Aides are refusing to put a timeframe on their introduction and also refused to set targets for reducing the number of asylum claims, small boat arrivals or deportations.

Mahmood wants to “begin the removal of families” to tackle the “perverse incentives” for parents to send their children on small boats to “exploit” UK laws by putting down roots to thwart removal.

But efforts to deport families will be one of the most legally contentious measures because of myriad laws designed to protect children, which will probably be used by refugee charities, immigration lawyers and political opponents to fight attempts to forcibly remove minors.

• Small boat migrants with children to be exempt from punishment

The Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 places a legal duty on the Home Office to act in a way that safeguards and promotes the welfare of children. A “best interests” assessment which considers a child’s health, education, stability and ties to the UK must be made before removal. Decisions must be “child-centred” and the Home Office has frequently been found to have acted unlawfully because it could not show it had discharged this duty.

Migrants board a small boat in Gravelines, France

GARETH FULLER/PA

The Children Act 1989 places a duty on authorities to provide accommodation for children in need and says the state’s role is to support and safeguard children, not leave them to face significant harm alone.

Steve Reed, the housing and communities secretary, said children would not be separated from their parents, a key tenet of the right to family life enshrined in Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The government would risk breaching the ECHR were children forced to live in countries to which they had few or no ties or where their schooling, healthcare and social development was disrupted.

Children who are British citizens cannot be deported unless the parents voluntarily take them out of the country or the child leaves because the parent is deported and they have no one else to stay with.

Children who have resided in the UK for seven consecutive years cannot be removed. The UN Refugee Convention prevents children being removed to a country where they risk persecution or degrading treatment or there are no suitable safeguarding arrangements on arrival.

How much will failed asylum seekers be paid to leave?

Labour has made greater use of financial incentives to encourage failed asylum seekers to return voluntarily to their home country and are offered up to £3,000 to do so.

• Keir Starmer promises to end asylum seekers’ ‘golden ticket’ to UK

Mahmood believes that voluntary returns encouraged through financial incentives offer the most cost-effective approach for UK taxpayers. They replace the need to detain individuals in immigration removal centres, which cost an average of £133 per person per night, and the greater cost of forcibly removing them on commercial and charter flights, which requires an average of five escorts per person.

Mahmood has vowed to carry out trials to see if larger payments would incentivise more people to leave, but the Home Office has not indicated how much extra they would be willing to pay.

It is unclear whether the new measures will reduce asylum claims

STEVE PARSONS/PA

It is also uncertain how public opinion will respond to paying illegal migrants thousands of pounds to go home. Last year voluntary returns cost the taxpayer £22.4 million, although that is a fraction of the £2 billion cost of accommodating asylum seekers.

How will judges be replaced in the oversight of asylum appeals?

The document sets out plans to replace the appeals process, which is overseen by judges sitting in immigration and asylum tribunals, with a new independent appeals body.

This will be staffed by “professionally trained adjudicators” appointed by the Home Office to identify individuals who have little prospect of a successful appeal, enabling their cases to be fast-tracked to deportation.

The Home Office has not set out details on how the body will identify these cases.

Officials have not said whether the new appeals body will replace the first tier tribunal and the upper tribunal, which oversees appeals from individual asylum seekers and challenges by the Home Office to their decisions.

Home Office sources signalled that the body would replace both tribunal tiers, so judges would no longer have a role in deciding whether to overturn appeals against rejected asylum claims.

The Home Office said the law did not require judges to make the final decision on asylum appeals and individuals would only be able to challenge a rejected asylum claim if it was based on an error in law.

How many refugees will be allowed to come on safe and legal routes?

Ministers want more refugees who arrive legally to get jobs and integrate into communities and will offer a shorter, ten-year pathway for those who arrive in the UK legally under new work and study routes. These will be capped. Those who are granted asylum can enter the pathway if they pay a visa fee.

Mahmood told MPs the scheme would “start modestly” in the “low hundreds” but numbers would grow over time.

Such low numbers are unlikely to deter small boat Channel crossings: too many want to reach the UK, and how quickly, or when, numbers will increase is unclear.

How long will it take and how much will it cost?

The Home Office said it will launch a consultation on the process for enforcing the removal of families, including children. It has not said whether primary legislation will be required to override laws governing the protection of children in the UK.

Deporting children is certain to be challenged in the British courts and possibly, if that fails, in the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

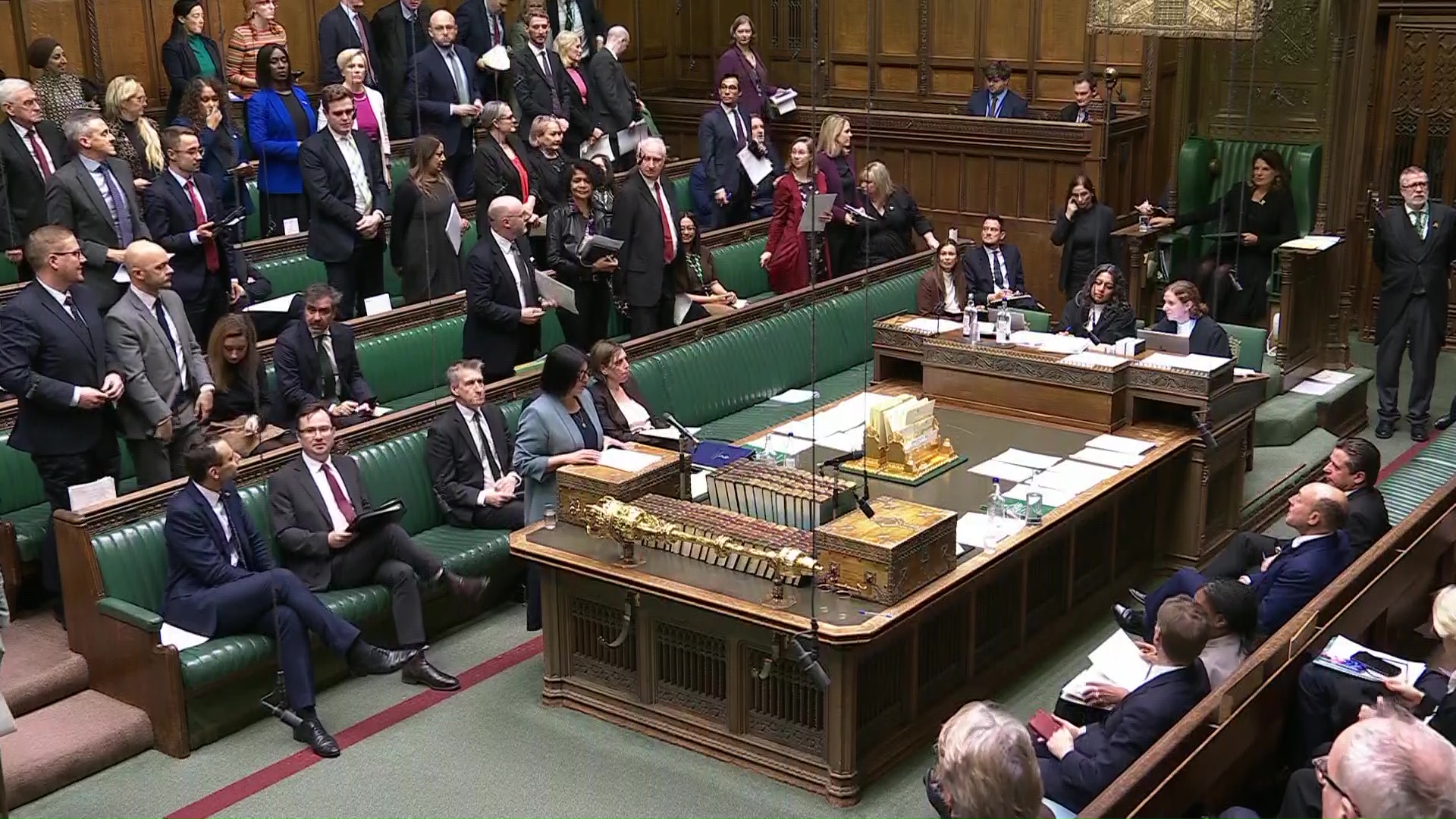

Mahmood laid out her plans in the House of Commons on Monday

HOUSE OF COMMONS/PA

This would delay the implementation of other measures, unless judges denied injunctions attempting to suspend action pending a full legal hearing.

Will these measures become a confidence vote in the government?

They will not be put to MPs in one chunk because some will require tweaks to existing legislation and immigration rules.

The most contentious measures — including the plans to make refugee status temporary and the 20-year wait for refugees to qualify for permanent settlement — are likely to require primary legislation that will have to be passed by both Houses of Parliament.

So far, the number of MPs expressing concern about the reforms are nowhere near the 80 or so that would be needed to threaten a government defeat.

The vast majority of Labour MPs have welcomed the measures or stomached them as the price of fighting back against Reform UK.

The figures who could cause the greatest strife for Sir Keir Starmer — Andy Burnham, Lucy Powell and Angela Rayner — have remained silent.

Mahmood’s allies also point to Denmark, where the Social Democrats held on to power by adopting hardline asylum and immigration policies.

The measures are unlikely to garner the degree of opposition seen over welfare reform and winter fuel payments.

Do the proposals have public support?

Polling has yet to be carried out on Mahmood’s measures. But More in Common conducted a poll last week asking British voters what they thought of Denmark’s policies, under which asylum claims dropped to a 40-year low.

It found strong support for each of the measures tested. Seven in ten voters supported the return of refugees when their countries become safe and 58 per cent backed temporary status for refugees over granting them permanent settlement. Among those who voted Labour last year, the measures attracted more support than opposition.