Guest post by Katrine Antonsen, Kjersti Lohne, Andreea Ioana Alecu. Katrine Antonsen is a doctoral researcher on the JustExports-project at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, University of Oslo. Kjersti Lohne is Professor and Head of Teaching and Learning at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, University of Oslo, and project leader of the research project JustExports—Promoting Justice in a Time of Friction: Scandinavian Penal Exports—funded by the Research Council of Norway. Lohne is also Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Andreea Ioana Alecu is Senior Researcher at Oslo Metropolitan University and Associate Professor at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, University of Oslo. This is Part 2 of a three-part mini series on Scandinavian Penal Aid.

Sweden is often viewed as a humanitarian superpower and a global ‘do-gooder’, recognised for its strong commitment to democracy and human rights in development aid. This commitment to humanitarian principles extends into the domain of criminal justice, where Sweden, along with its Scandinavian counterparts, has long been regarded as a global role model. For decades, it has made contributions to human rights initiatives within criminal justice systems worldwide, implying that Scandinavian penal exceptionalism extends beyond the nation state.

However, as Sweden navigates its role in the international arena, it faces critical questions related to its domestic criminal justice policies. With rising concerns over crime, immigration and the politicisation of criminal justice, Swedish criminal justice policy reflects a shift towards a more punitive stance—a marked departure from the country’s historical emphasis on rehabilitation and welfare. In combination with a changing geopolitical landscape, with heightened focused on security, migration, and transnational crime, Sweden’s position as a global role model in criminal justice and development aid may be under threat. Our dataset provides a baseline for exploring some of these dynamics, with unique data on some of the ways in which Sweden’s humanitarian role internationally intersects with crime and criminal justice through their foreign aid engagements.

The Swedish penal aid dataset is based on the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) database on Swedish development aid statistics. It includes development aid budget registrations from 1990 to 2022 that includes elements of penal exports. Penal exports are exports of models, money, personnel, institutions, laws, technologies, and epistemologies related to the complex of crime and justice. The dataset covers 12,509 agreements. While early data is less precise due to incomplete records, reliable information is available from around 1998 onwards. From the mid-1990s, there has been a steady and significant increase in disbursements to agreements including penal aid, with total disbursements nearing $600 million USD by 2021.

Which countries receive Swedish penal aid?

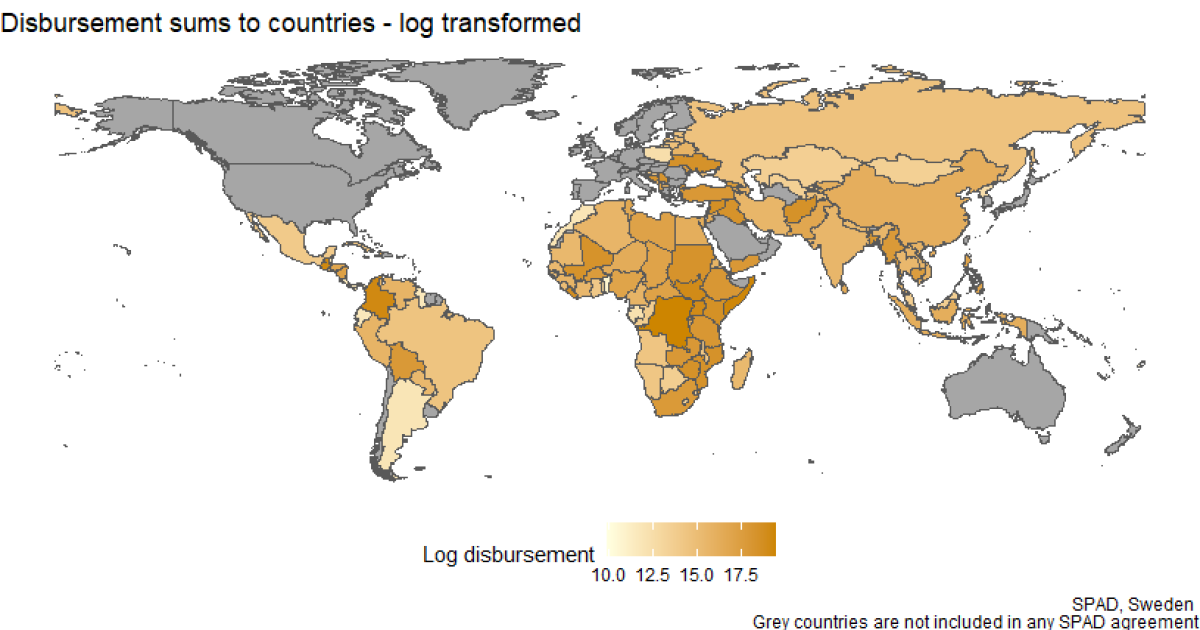

The data includes both bilateral agreements and those involving multiple partners or regions. In the 1990s, Sweden maintained agreements with approximately 30 countries, but by 2021, this number had expanded to 101. Over the 30-year period, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Guatemala, Colombia, and Uganda have received the most funds to aid projects that include elements of penal exports.

Figure 2: illustrates the logarithmic transformation of total disbursements allocated to individual countries by Sweden

Figure 2 illustrates the disbursements allocated to individual countries from Sweden. In addition to country-specific agreements, there has been a notable increase in the share of penal aid disbursements allocated to projects with a regional or global focus. In the 1990s, approximately 80% of disbursements to penal aid were directed toward agreements with a specific recipient country, but by 2022, this share had declined to 60%. This trend highlights a growing emphasis on projects with a multinational or broader scope over the period.

Through which discourses do Swedish penal aid travel?

Sida publishes its development aid statistics and data according to the IATI standard: key to these registrations is the use of OECD-DAC purpose codes (‘sector codes’), being a ‘list of codes, names and descriptions used to identify the sector of destination of a contribution’. Sida applies these codes to categorise the specific areas of the recipient country’s economic and social structure that the funding is intended to support.

The coding of the intended purpose allows for a categorisation of the discourses that legitimate penal aid. The purpose codes highlight how the focus of penal aid fluctuates over time, revealing shifting priorities that are influenced by geopolitical conditions and events. At times, penal aid has been justified primarily on human rights grounds, while at others, it has been framed as a means of conflict prevention, implying diverse intended purposes for supporting criminal justice systems in other countries.

Figure 3: Bar chart showing which sectors which make up 10% or more of yearly disbursements from Sweden

The trends presented in figure 3 suggest that Swedish penal aid has diversified over time, moving away from a heavy focus on specific sectors like “legal and judicial development” and “human rights”. By the end of the study period only 50% or less of the projects can be classified by looking at which sectors receive 10% or more of the yearly disbursements. Peacekeeping operations have maintained a moderate but steady presence, with no clear long-term growth or decline trend. The “human rights” sector experienced early prominence but later stabilised at lower levels (fluctuating around 10–15%). Lastly, the data on “material relief assistance and services” reveal a significant increase in disbursement shares during the early 2010s, peaking at 30.7% in 2011 and maintaining high levels through 2015. This period likely reflects Sweden’s response to global humanitarian crises, possibly linked to conflicts, natural disasters, or refugee movements. However, after 2016, there is a clear downward trend, with disbursements dropping to 12% by 2022.

Who are the actors involved?

In the Swedish case, multilateral organisations receive the largest share of disbursements to penal aid projects (51.1%), followed by NGOs (38.5%), with international NGOs accounting for the majority (22.4%) and national NGOs at 10.7%. Governments and regional NGOs each manage around 5.3%, while academic institutions account for 2.2%. Smaller shares are allocated to public-private partnerships (1%) and other entities (0.6%), with a small portion of data missing (1.4%).

Figure 4: Bar chart showing the percentage of yearly disbursement allocated to the different agreement partners.implementing organization type

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, governments received a significant share of disbursements to penal aid, peaking at 24.7% in 2002, while multilateral organisations were responsible for a consistent but slightly lower share. From 2009 onward, however, the balance shifted dramatically in favour of multilateral organisations, whose share progressively increased, dominating allocations with 63.2% in 2020 and 54.8% in 2022. In contrast, government-managed disbursements steadily declined, dropping to 1.7% in 2020 and remaining below 2% in subsequent years.

International NGOs are consistently responsible for implementing the largest share of penal aid amongst NGOs, with notable peaks such as 35.9% in 2011 and 31.6% in 2013. Their share, however, fluctuates, dropping to 13.3% in 2018 before rebounding to 28.1% in 2021. National NGOs maintain a smaller but stable presence, with shares generally between 5% and 15%, and become more prominent implementers in recent years. Regional NGOs, while receiving the smallest share, demonstrate consistent involvement, typically ranging between 3% and 7%. These trends indicate a reliance on international actors for large-scale initiatives, while national and regional NGOs play complementary roles.

Conclusion

These descriptives highlight some of the analytic insights that can be gained from further exploration of the Scandinavian Penal Aid Dataset (SPAD), which we aim to make openly accessible soon. In the case of Sweden, the historical data covering the period from 1990 to 2022 may provide researchers with insights into how its longstanding humanitarian reputation has historically intersected with its approach to criminal justice, while also serving as a baseline for analysing changing dynamics in response to emerging global and domestic challenges. SPAD also allows for an analysis of Sweden’s practices in relation to the other Scandinavian states, facilitating a comparative approach to the study of criminal justice exports and what it may tell us about the power to punish—beyond borders.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or find us on LinkedIn and BlueSky.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

K. Antonsen, K. Lohne and A. I. Alecu. (2025) Descriptive statistics from penality on the move. Part 2: Swedish Penal Aid . Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2025/11/descriptive-statistics-penality-move-part-2-swedish. Accessed on: 19/11/2025