Hours before President Donald Trump announced a return to U.S. nuclear testing “on an equal basis,” he made another surprise announcement: He had given South Korea “approval to build a Nuclear Powered Submarine.” Acquiring a conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarine, or SSN, has been on South Korea’s defense wish list for years—but even Seoul was caught off guard. This proposed capability raises critical questions that lack clear answers.

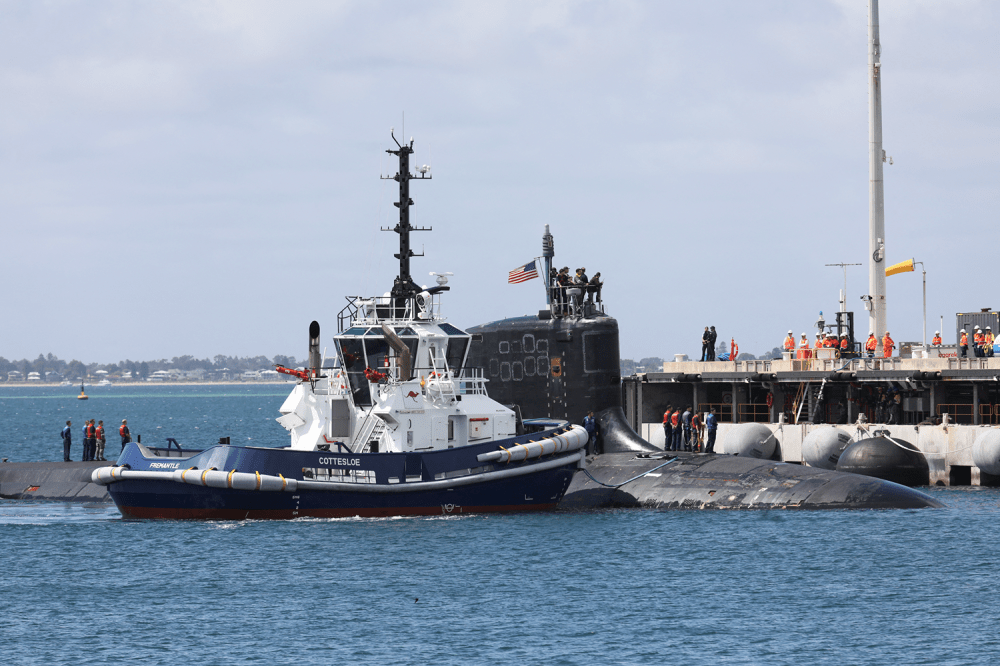

To date, only nuclear-armed states have developed and deployed nuclear-powered submarines. But South Korea would not be the first nonnuclear state to pursue this technologically difficult and politically sensitive capability. Australia and Brazil are in the midst of the long process of acquiring SSNs.

Hours before President Donald Trump announced a return to U.S. nuclear testing “on an equal basis,” he made another surprise announcement: He had given South Korea “approval to build a Nuclear Powered Submarine.” Acquiring a conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarine, or SSN, has been on South Korea’s defense wish list for years—but even Seoul was caught off guard. This proposed capability raises critical questions that lack clear answers.

To date, only nuclear-armed states have developed and deployed nuclear-powered submarines. But South Korea would not be the first nonnuclear state to pursue this technologically difficult and politically sensitive capability. Australia and Brazil are in the midst of the long process of acquiring SSNs.

The Australian and Brazilian SSN models are distinct in design, nuclear fuel type and sources of supply, and the depth of foreign partnerships involved. Australia has partnered with the United Kingdom and United States through the AUKUS arrangement. Early indications, including a joint fact sheet released after Trump’s visit to South Korea, suggest that Seoul might follow the Australian model, by which it could partner with the United States and perhaps another country to design and produce the boat and fuel.

Most importantly, the United States would provide the nuclear fuel—enriched uranium—for the submarines, so South Korea would not need its own enrichment capability for fuel production. This model would, though, require a significant set of amendments to existing agreements and new arrangements for Washington to share sensitive military technology with Seoul. This would be a significant departure from the previous U.S. position that the transfer of SSNs and associated technology to Australia was a “one-off.”

If the two sides cannot reach an acceptable arrangement on the transfer of U.S. fuel, South Korea could instead pursue the Brazilian model. It might receive help from the United States in designing the nonnuclear components of the submarine—akin to France’s assistance to Brazil—but would need to develop an entirely indigenous nuclear reactor to power the boat. It would also need to produce the nuclear fuel to power that reactor. South Korea does not currently have its own enrichment capability, and its civil nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States restricts cooperation on enrichment. The joint fact sheet indicates that this could change in the future, but much remains to be negotiated.

A closely related issue is whether South Korea would fuel its SSNs with low-enriched uranium (LEU) or highly enriched uranium (HEU). Seoul reportedly sought U.S. provision of LEU fuel in the past, suggesting a naval reactor more like Brazil’s LEU design. LEU cannot be used as readily in nuclear weapons as HEU and thus in and of itself raises fewer security concerns. However, HEU-fueled submarines do not require refueling during their service lives and have some additional performance benefits.

The United States uses HEU-fueled SSNs and, under the phased approach to the AUKUS agreement, plans to eventually transfer HEU fuel to Australia for its future SSN fleet. Regardless of the level of enrichment—and whether South Korea makes its own fuel or receives it from the United States—Seoul will need to negotiate a special safeguards arrangement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

There are presumably other pathways South Korea could pursue beyond the Australia and Brazil models, even with U.S. assistance. Trump clearly indicated an expectation of U.S. involvement given his follow-on post about building these submarines in the “Philadelphia Shipyards,” a reference to Hanwha Philly Shipyard, recently acquired by the South Korean group. But that shipyard is not kitted out with the facilities and capabilities needed to construct nuclear-powered boats, and South Korean officials are insistent that the submarines will be built in South Korea.

But why does Seoul even want a nuclear-powered submarine in the first place? SSNs have some operational advantages over what Trump described in his original post as “old fashioned, and far less nimble” diesel-powered submarines: They can be faster and stealthier and travel farther and stay submerged longer than their diesel-powered equivalents. But they’re also expensive—financially, politically, and otherwise.

The speed and stealth of these submarines could help South Korea prepare for North Korea’s pursuit of its own nuclear-powered submarine, which it likely plans to equip with nuclear weapons. South Korean SSNs could potentially threaten this future leg of North Korea’s nuclear deterrent. If, however, North Korea relies on this future fleet as a secure second-strike capability, holding at risk that capability could significantly affect Pyongyang’s strategic calculus.

The ability of SSNs to travel longer and farther could potentially contribute to burden-sharing efforts with the United States. South Korean President Lee Jae-myung indicated that the submarines could allow South Korea to better track North Korean and Chinese vessels, alleviating the operational burden on U.S. forces. The question remains, though, whether this blue-water capability is needed to track those assets and whether the United States would rely on it in a crisis or conflict with China.

Beyond these operational attributes of SSNs, some in Seoul may have a very different interest in mind: using the SSN program as justification for a uranium enrichment capability that could contribute to the country’s nuclear latency. There is a long-standing debate in South Korea over whether to develop a nuclear weapons capability to address the growing threat from North Korea. This debate has gained momentum in recent years, fueled by consistent levels of (potentially underinformed) public support for nuclear weapons, anxiety over Washington’s extended deterrence commitment, and comments from former President Yoon Suk-yeol that South Korea could develop nuclear weapons “pretty quickly.”

While Yoon’s comments were walked back and the Lee administration has since reaffirmed South Korea’s commitment not to develop nuclear weapons, there remain vocal advocates for maintaining the nuclear option. An enrichment capability would contribute significantly in this regard.

Meanwhile, in a model where the United States is central to both design and fuel supply, these SSNs could serve as an important status symbol. South Korea would become only the third country—after the U.K. and Australia—with which the United States would share this coveted and most sensitive naval technology.

Partnering with the United States to build an SSN program would see Seoul doubling down on its alliance with Washington—at a time when many in South Korea are concerned about U.S. security commitments amid fears that the Trump administration might reduce the size of U.S. Forces Korea.

Some commentators have interpreted this doubling down as a strategic move aimed at positioning South Korea to directly contribute to and fortify U.S. industry. The South Korean desire for an SSN capability could also indicate a willingness to broaden its involvement in regional security beyond the Korean Peninsula. Because SSNs can travel farther for longer, a South Korean SSN could contribute to efforts to promote greater regional stability. But none of this would happen in a vacuum, and serious questions remain about how others, namely Beijing, might respond to this expanded role.

There are legal and political questions around the capability, too. Developing a conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarine would not prima facie violate South Korea’s nonproliferation obligations. Naval nuclear propulsion is a non-proscribed military use of nuclear material according to South Korea’s safeguards agreements with the IAEA. But Seoul would have to negotiate a special arrangement to remove that material from normal safeguards procedures, as required by its comprehensive safeguards agreement, while it is being used as submarine fuel.

Australia and Brazil are in the midst of such negotiations with the IAEA. This has been a yearslong process during which both states have faced numerous challenges, including international pushback. South Korea could expect to face even greater pushback, and some critics may even go so far as to accuse South Korea of pursuing SSNs as a cover for a nuclear weapons program.

North Korea has already done so, indicating that it will respond with “more justified and realistic countermeasures.” China also raised nonproliferation concerns in an immediate response to Trump’s announcement and cautioned Seoul to proceed “prudently.” Beijing’s diplomatic campaign against the AUKUS SSN program, or its political and economic response to the deployment of a U.S. missile defense system in South Korea, might be a model for how it would react to the development of South Korean SSNs.

Beyond these adversarial responses, Seoul could also expect mixed reactions from its regional partners and allies, namely Japan and Australia, which may question the impact of this South Korean capability on allied deterrence. Japan, for example, has already indicated that it may need its own SSN capability following Trump’s announcement.

Ultimately, further clarity and more detailed analysis are needed to understand and best prepare for a future South Korean SSN capability. The joint fact sheet provides few details, which could take many months or even years to work out. Its delay and reports of early divisions between Seoul and Washington (and within Washington) on the matter portend many difficulties ahead.

South Korea will also need to think through the implications of acquiring this capability, especially as relevant to the nonproliferation dimensions of naval nuclear propulsion by nonnuclear states. The international community will want clarity on how South Korea will continue to deliver on and demonstrate its commitment to its nonproliferation obligations. How can South Korea become a responsible steward of naval nuclear propulsion?

Whatever the decisions in Seoul, there are choppy waters ahead.