In this Aug. 28, 2018 photo, the skull of one of Franco’s victims is examined during the classification process by anthropologists following the exhumation of a mass grave found in Paterna, near Valencia, Spain. | AP

“Spaniards, Franco has died,” came the announcement 50 years ago on Spanish TV. If there was any truth to the widely held story that Barcelona immediately ran out of cava, the corks would have been popping behind closed doors.

Most Spaniards held their breath on Nov. 20, 1975, fearful of what might happen next. After nearly four decades of brutal dictatorship, reactionary forces dominated the country’s institutions and the generalissimo himself had boasted that everything was being left “well tied up.”

Confounding expectations, however, King Juan Carlos appointed a government that steered Spain towards free elections in 1977, the first since the Spanish Republic. In 1981, he helped face down a botched coup attempt by die-hard army and civil guard units, who briefly seized the Cortes, the Spanish parliament.

In the following year, the PSOE (Spanish Socialist Workers Party)—the dominant party in the Spanish Republic’s Popular Front government of 1936-39—won the general election.

Today, Juan Carlos, who abdicated in favour of son Filipe in 2014, is again at the center of controversy. His autobiography praises Franco’s “intelligence and political sense.” But it says nothing in 500 pages about the victims of Franco, nor the scars that the Spanish Civil War left on Spanish society.

General Francisco Franco, pictured in Vinaroz, Spain, in July 1938, during the Spanish Civil War. Tens of thousands were murdered during his 40-year fascist dictatorship. | AP

General Francisco Franco, pictured in Vinaroz, Spain, in July 1938, during the Spanish Civil War. Tens of thousands were murdered during his 40-year fascist dictatorship. | AP

Publication of the memoir comes at a time of heightened political tensions in Spain. The far-right Vox party is surging in the polls. In half-a-dozen autonomous regions, the party props up right-wing administrations fronted by the more mainstream Popular Party (PP)—which is itself a haven for Franco apologists.

The anniversary of the dictator’s death has also seen anti-immigrant fascist groups on the streets of Madrid giving Nazi salutes, singing Francoist anthems, and waving SS-inspired flags.

Though many have applauded Juan Carlos’s role in Spain’s transition to democracy, they often overlook the tide of popular agitation that forced his hand.

Hailed as a triumph of peaceful top-down politics, the “Transición” was far from bloodless. Hundreds died in political violence, including terrorist attacks by a shadowy far-left group, GRAPO (Grupo de Resistencia Antifascista Primero de Octubre / First of October Anti-Fascist Resistance Groups), that is now known to have been heavily penetrated by Francoist secret police.

Among the worst atrocities was the assassination in 1977 of five Communist lawyers by fascist gunmen in Madrid’s Atocha Street. More than 100,000 people attended their funeral—one of the first mass demonstrations since the Caudillo’s death. This was followed by strikes and displays of solidarity across the country. A few weeks later the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) was legalized.

The blood on Franco’s hands never dried. After launching the military uprising that sparked the country’s civil war in 1936, he climbed to power over the dead bodies of more than 150,000 summarily executed Republicans, leftists, and trade unionists. Their toll easily outnumbered the victims of revenge attacks against supporters of the coup.

Victory in 1939 was secured courtesy of troops, aircraft, and weapons sent by Hitler and Mussolini. When their planes mercilessly bombed Guernica, Barcelona, and Madrid, the world was shocked.

Even when the war ended, the systematic torture and killings continued in Franco’s vast network of penal camps. In 1940 in Madrid alone, there were 30 prisons housing 100,000 Republican prisoners, a quarter of them on death row.

And so it went on, year after year, with the terminally ill Franco signing the last five death warrants as he was about to climb into his deathbed.

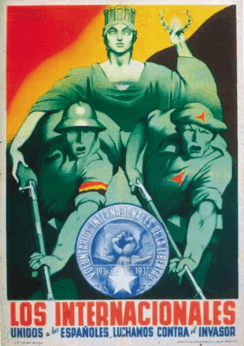

“The Internationals—United with the Spaniards, We Fight the Invader,” poster by Parrilla, published by the International Brigades, 1936–37.

“The Internationals—United with the Spaniards, We Fight the Invader,” poster by Parrilla, published by the International Brigades, 1936–37.

There had been a glimmer of hope at the end of World War II that Franco’s regime, by then an international pariah, might be toppled. But the U.S. cavalry rode to the rescue, finding in Franco a dependable anti-communist stooge during the Cold War. Generous long-term loans began in 1950, and three years later, the U.S. was handed Spanish air and naval bases in exchange for more economic and military aid.

Spain today is a vibrant, open society, though one with all the familiar social problems of advanced Western liberal democracies. Scratch the surface, however, and historic divisions open up, and old attitudes forged by 40 years of censorship and the dictatorship’s lies re-emerge.

It wasn’t until the start of this century—a full 25 years after Franco’s death—that the unofficial pact of silence that accompanied the return to democracy was broken.

Younger people began asking what had happened to their grandparents during the war, why they didn’t have a grave, and why no one dared speak about it. Soon they found out the awful truth that Spain is a country covered with mass graves of Republicans. There were, and still are, thousands of them—including ones with remains of International Brigadiers whose bodies were dug up and dumped after Franco won the war.

The man who initiated the first exhumation was Emilio Silva. He was trying to find the remains of his grandfather in the village of Priaranza del Bierzo in northwest Spain. But in the process, he launched a social movement of Spaniards demanding to know the truth about the past.

“What I wanted was to bury him with my grandmother and go back to my life as a journalist,” Silva recalled in a recent interview. “I thought I was going to return to how things were before finding the mass grave, but everything became unstoppable.”

Many thousands of murdered Republicans have since been given proper burials, though it is estimated that the remains of more than 100,000 of Spain’s “disappeared” still lie unidentified in the Spanish soil.

Propelled by this mass movement for the recovery of historical memory, the PSOE-led governments of José Luis Zapatero and current prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, have made worthy efforts to help Spain come to terms with the crimes of Francoism.

Memory laws have acknowledged old injustices and addressed the issue of mass graves. Streets glorifying fascists have been renamed. Franco’s body was removed from the grotesque mausoleum he built for himself with Republican slave labor northwest of Madrid. Exiles, International Brigadiers, and their descendants have been welcomed as Spanish citizens.

Unsurprisingly, Vox and the PP have resisted all these moves, with regional authorities led by them rolling back memory laws and refusing to identify and protect mass graves. Yet, as one historian has pointed out, Spain is the only country in western Europe where it is possible to randomly dig a hole in the ground and run the risk of unearthing human remains.

This is an abbreviated version of an article that appeared in Morning Star.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today.