Seeing no pathway to reach compliance with federal ozone standards by 2027, Colorado regulators voluntarily downgraded the state’s status with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency on Friday — a move that will buy them more time to try and reduce air pollution.

In doing so, however, the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission resisted efforts from the business community to seek a federal designation that would have eased some restrictions, as well as efforts from environmentalists to add regulations on oil and gas. And while the final State Implementation Plan that the AQCC passed unanimously is hardly a stay-the-course roadmap — it seeks to reduce ozone precursors from drilling wells 50% by 2030 — it also acknowledged improvements that have come from existing regulations.

“Maybe we haven’t made as much progress as we’d like,” commissioner Curtis Rueter said shortly before passage of the updated SIP. “But at the same time, we’ve made some tremendous progress on several fronts.”

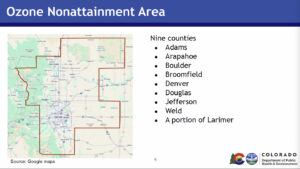

A large swath of the Front Range has been out of compliance since 2012 with EPA standards requiring ozone concentrations below 75 parts per billion, and a larger section extending to the Wyoming border is noncompliant with a new 70-parts-per-billion standard. To try to reach compliance, Colorado mandated emissions-reduction rules on sectors from oil-and-gas to industrial facilities to commercial buildings in recent years, and gas stations in the nonattainment area began selling higher-priced reformulated gas last summer.

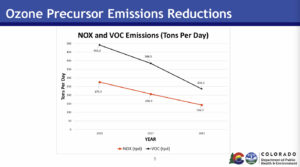

Ozone precursors falling

A Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment graphic shows how much ozone precursors have dropped since 2011.

The strategies have produced some success stories. Emissions of nitrous oxide and volatile organic compounds — the precursors to ozone — are down nearly 50% since 2011, explained Jessica Ferko, planning and policy program manager for the Colorado Air Pollution Control Division. VOC emissions have fallen from 491.2 tons per day to 236.5, and NOx emissions dropped from 275.5 tons per day to 142.7.

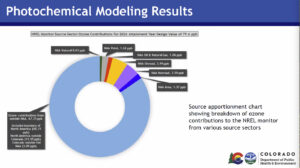

But ozone levels remain stubbornly close to 77 parts per billion, leading to health problems including pulmonary conditions and exacerbation of afflictions like asthma, explained Mike Silverstein, executive director of the Regional Air Quality Control Council. Though locally man-made ozone represents the minority of those parts, with most of the pollution coming from national and international sources or from natural causes like wildfires, Colorado still must work to reduce emissions from drills, cars and a lot of other sources.

With no viable path to cut ozone enough to avoid the whole northern Front Range being downgraded from serious to severe noncompliance by 2027, APCD officials chose instead to voluntarily downgrade the state, delaying its next compliance requirements until 2032. This will allow emissions-reduction strategies to fully mature and show more impact, Ferko told the AQCC during a two-day hearing, and it removes the need for the state to do extensive modeling immediately and propose unrealistic compliance pathways.

Several groups, including the Colorado Chamber of Commerce and Colorado Oil & Gas Association, urged the state to file a 179B designation seeking exemption from downgrade by arguing the Front Range would be in compliance if not for international emissions. Ferko agreed to brief the AQCC more on that potential process at a future date, but commissioners said they didn’t have enough information yet to take that step forward.

What’s in the State Implementation Plan

A Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment map shows the ozone nonattainment in the northern Front Range.

Instead, they updated the SIP by taking several emissions-cutting steps that were agreed to by all parties. Those included new regulations on certain aerospace coatings and the continuation through 2030 of a two-year-old NOx emissions-intensity-reduction program that is set to cut emissions of those compounds 50% by 2030 as compared to 2017 levels.

The Local Government Coalition — a 47-member organization representing areas like Adams, Boulder and Broomfield counties — asked the AQCC to go further and set mass-based limits on upstream oil-and-gas emissions, essentially capping production. This was needed, officials from that group said, because if oil and gas production grows in the next five years, it could boost rather than reduce the amount of emissions from that sector if drillers are required only to lower their emissions intensity.

“This rulemaking is not designed to get Colorado into compliance,” lamented Lindsay Ex, policy director for Colorado Communities for Climate Action. “More solutions and more strategies are needed.”

Ferko argued, however, that the reduction in NOx and VOCs shows that the emissions-intensity cutbacks are leading to overall emissions reductions and that mass-based limits would neither be helpful nor easily enforceable. If the sector did not reach its limit, she asked, who exactly would be responsible for making further mandatory cuts?

“The emissions inventory has been vetted by a lot of people. I’m confident it will result in mass reductions as well,” said commissioner Gregg Thomas before AQCC members voted unanimously against the LGC’s request.

A debate over minor modifications

Beyond that issue, there were a few specific provisions in the SIP that triggered significant debate during the hearing.

APCD staffers, for example, wanted to change the current permitting process for minor modifications — facility upgrades at major-emitter sites that are designed to allow greater production and could result in small increases of NOx or VOC emissions. Companies applying for minor-modification permits now can proceed with work immediately under state rules, but division leaders wanted to require that some of these projects instead go through a period of public notice and public comment.

Leah Martland, supervisor for APCD’s planning and policy regulatory team, noted that the division signed an informal agreement with the EPA in January to get more public comment on minor modification procedures. And commissioner Jana Milford said she believed it was important to take that step to show that the AQCC wants to hear input from communities like Commerce City that are near high-emitting industrial sites and be transparent about what regulators are allowing.

Dave Kulmann is the regulatory affairs advisor for the Colorado Chamber of Commerce

Colorado Chamber regulatory affairs advisor Dave Kulmann argued, however, that requiring even minor changes to go through the division’s lengthy, backlogged construction-permitting process could turn a four-month project into one that takes two years. And Carlos Romo, an attorney representing the Colorado Petroleum Association, said the change would make Colorado the first state to require public notice for minor modifications — all because of a non-binding resolution with the EPA.

“This is one of the few instances where we actually have a semi-streamlined permitting process in the division. Please don’t take that away,” Kulmann pled with commissioners before they voted 6-3 not to change the minor-modification process.

Emissions reduction credits

Commissioners OK’d an APCD plan to modernize the issuance of emissions reduction credits, a currently rarely-used process in which emitters can take voluntary actions like shutting down a producing well and get credits to help them meet their emissions limits. And they agreed to not foreclose the potential of offering those credits for mobile-source emissions cuts for actions like vehicle electrification in the future if those sources are ever subject to review permitting — an action that frustrated some environmentalists.

However, the commission did not go as far as groups like COGA and the American Petroleum Institute Colorado had asked them to in directing that actions like well shutdowns be awarded such credits automatically. Martland argued successfully that the credits must be considered on a case-by-case basis and can’t be given automatically if a company were to shut down one well while increasing emissions from other equipment.

Commissioners avoided having much discussion on the Blueprint submitted by the RAQC that recommends consideration of a host of future regulations or best practices on a wide range of sectors in order to achieve greater emissions reductions. The document garnered attention particularly for its suggestions to consider regulations on indirect sources of emissions that attract significant vehicle traffic, from airports to warehouses to sporting arenas, by trying to limit the traffic of gas-powered vehicles to them.

More suggestions for reducing ozone to come

A Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment chart shows how much of the state’s ozone problem comes from sources outside of state regulations.

While the LGC emphasized that it endorsed all the suggestions in the Blueprint, Silverstein said his group was submitting the proposal not for inclusion in the SIP but to spur ideas about further ways that the AQCC could look to get to compliance. He asked only that the RAQC be allowed to come back and brief the commission on potential benefits to the strategies as it undertook further study on their efficacy.

“Our job is to send you plans to reach attainment with federal standards,” said Dan Kramer, the Estes Park town attorney who chairs the RAQC board. “Some of what we propose may be expensive to implement, but there is nothing we don’t expect to pay off, especially in the health of our communities.”

While business leaders generally expressed satisfaction with the updated SIP — attorneys for COGA and API noted particularly how they support the approved plan to reduce NOx and VOC emissions further by 2030 — AQCC members expressed mixed feelings.

Will updates help public health?

Milford, for example, voiced disappointment that the state must take a compliance downgrade and defer federal judgment on its emissions-cutting efforts until 2032. But she, like APCD officials, said that the state can’t take its foot off the gas and must look for emissions reductions that will have more substantial impacts on air quality.

“In the end, what we’re doing is we spend a lot of time with these procedures, and really, we very seldom use the word ‘public health,’” commissioner Jon Slutsky said. “I wish we could do it a little sooner.”

But Chris Colclasure, a COGA attorney, emphasized any high-cost regulations imposed by the AQCC that couldn’t account for substantial-enough reductions to reach compliance would only impose burdens on Colorado businesses without producing progress. And he pointed to the substantial NOx and VOC cuts the state already has made and said that feasible steps will continue to reduce that pollution, even if cutting ozone is harder — a sentiment that seemed to land with at least one commissioner.

“We’ve made some great progress as a region in terms of precursors. The fact that ozone response is not there is very frustrating,” Thomas said.