The Visegrad Group faces diminishing influence as shifting interests and politics reshape Central Europe’s model for cooperation.

The prime ministers of Slovakia, Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary stand somewhat uncomfortably next to one another at their Prague summit in February 2024, their most recent. They have not met in 2025. © Getty Images

The prime ministers of Slovakia, Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary stand somewhat uncomfortably next to one another at their Prague summit in February 2024, their most recent. They have not met in 2025. © Getty Images

Divergent national politics hinder V4 stances on security and integration

Pressure from Russia and China exacerbates divisions among V4 members

Regional cooperation favors broader initiatives over V4 efforts

Founded in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Visegrad Group (or V4) is a regional platform of four Central European countries: the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. It represented one of the first efforts of European states in the post-Cold War era to jointly pursue a common agenda to advance their interests outside formal multinational structures. At the time, none of the nations belonged to NATO or the European Communities, which later became the European Union.

Today, geopolitics is a world apart. In contemporary Europe, the place for informal multinational partnerships may be more, not less, relevant than it was over three and half decades ago. But the V4, though an important model, will likely not be one of the more influential groups shaping the future of Europe and the transatlantic community.

The many faces of multilateralism

In the post-Cold War world there was a significant proliferation of international and multinational structures. Despite the increased formality of global and regional organizations, more informal groupings have persisted and in some cases grown in relevance.

The continued utility of such minilateralism demonstrates the limits of the global rules-based order framework. If structural institutions effectively managed global affairs, fewer minilateral groups would have emerged. They range from “coalitions of the willing” to periodic coordinating assemblies like the Quad (Australia, India, Japan and the United States) and more interest-based groups with secretariats like the Organization of Turkic States (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkiye and Uzbekistan, with Hungary, Turkmenistan and Northern Cyprus as observer participants).

In the last four years, substantial policy differences among the governments have rendered the V4 format moribund.

There is no question that both ad hoc and regularized groups play important roles. Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia, for instance, commonly advocate for Baltic security through multiple platforms, including holding combined 2+2 (ministers of defense and foreign policy) meetings with their U.S. counterparts. The Czech Republic’s munitions initiative, in which Prague assembled a coalition of nations from around the globe to provide conventional ammunition to Ukraine, is another example.

While the utility of formats like the V4 remains clearly relevant, this particular group and its struggle to find common ground reflect the challenges of implementing minilateralism in modern Europe.

Interests and politics in Central Europe

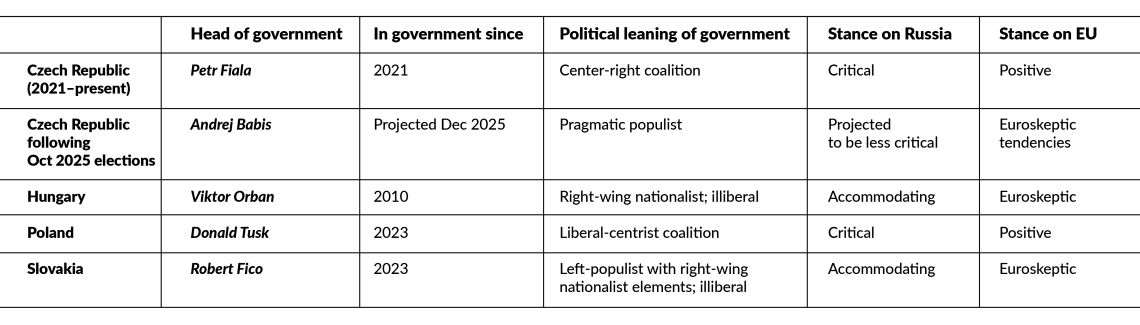

In the last four years, substantial policy differences among the governments have rendered the V4 format moribund. The same divisions also demonstrate the limitations of more formal structures like the EU and NATO. This year, with the group split into two factions, Poland and the Czech Republic on one side and Slovakia and Hungary on the other, there have been no V4 summits.

The issue publicly dividing them is Russia’s continued war against Ukraine. All support the NATO commitment of 5 percent of gross domestic product to defense, and all in one manner or another have provided support to Ukraine. Yet Slovakia and Hungary discount the threat Russia represents to Europe. In turn, they oppose bans to Russian energy imports as economically harmful.

The divisions, however, are more complicated than differences just over security policy. Both Budapest and Bratislava have opposed deeper political integration under the EU (namely on issues such as immigration and borders) and have chafed at Brussels’ actions and policies punishing their governments for not falling in line and for their efforts to throttle domestic political opposition.

The populist policies of Slovakia and Hungary may be unpopular elsewhere in Europe, but they resonate strongly with voters at home and have helped sustain both governments’ support. These positions, however, have put them in sharp contrast with the present governments in Poland and the Czech Republic and have significantly strained high-level policy engagement. In fact, today there is virtually no common alignment among the V4 countries on key foreign policy and EU issues.

In 2024, when the center-left Polish government took the V4 presidency, it announced a “Back to Basics” initiative calling for a return to the original values of cooperation: freedom, human rights, the rule of law, European integration and security. The initiative fell completely flat, ignoring the core differences dividing the governments. Instead, the Warsaw government in practice discouraged cooperation by pressuring the more populist regimes to fall in line.

The troubles of the V4 reflect the importance of aligning interests and politics in sustaining minilateral partnerships. Before membership in the EU, the Visegrad nations all faced similar challenges and goals, namely modernizing their economies and infrastructure, becoming members of the transatlantic defense alliance and assimilating into the European framework. Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic joined NATO in 1999 and Slovakia in 2004, the year they and six other countries became EU members. Now, with some issues of EU integration settled (all four countries, for example, are in the Schengen Area), the need for coordinated policies has dwindled. The countries face diverse internal political pressures, and with Slovakia the only eurozone member among the four, they are also monetarily split.

The V4 stands in stark contrast with the Baltic states, where common security concerns have not only forged common policies, but now are increasingly driving more cooperation with Nordic countries as well.

Nevertheless, the V4 continues to operate at the functional level, supporting programs such as cultural and education exchange through the International Visegrad Fund. The countries remain interested in sustaining person-to-person contacts, even as geopolitical action at present is off the table.

Despite deep disagreements and tension, dissolving the V4 is not currently on any nation’s agenda. In fact, following the Czech parliamentary elections in October, leaders of the winning party, ANO, have said they intend to rejuvenate V4 cooperation. The framework continues to have utility, such as in coordinating cross-border and sectoral matters, or addressing the Ukraine grain export corridor issue. Abolishing the format would be a mutual embarrassment, signaling the abandonment of a long-standing symbol of regional brotherhood.

Central Europe faces challenges from the east

Ironically, the differences among the V4 have been least affected by the issue which publicly divides them the most – Russia’s war in Ukraine and future security policy. While governments in Budapest and Bratislava want to prioritize normalizing relations with Moscow, none in fact want Russia to have a more dominant geopolitical role in their neighborhood, nor are they opposed to strengthening NATO’s conventional deterrence structure.

Russian efforts to exacerbate divisions among the V4 are not insignificant, whether through diplomacy, disinformation or hybrid attacks. Russian-backed websites, for example, now generate more content than traditional domestic media outlets in some Central European markets. Moscow’s influence, however, is not the main engine of discord. Domestic issues have been far more significant in driving internal policies than external pressure from Moscow.

Read more by national security and foreign policy expert James Jay Carafano

A greater geopolitical challenge for the countries is China. Beijing favors bilateral relations with individual countries in Europe to thwart European cohesion and the EU’s economic competitiveness as a cohesive trading bloc. It serves China’s interest to have Central European nations split and open to its influence. Some members, like Hungary, are unconcerned about strategic dependencies on Beijing, while the Czechs are among the most vocal European critics of Beijing’s policies. This gap creates vulnerabilities for the region that could be more effectively addressed by common V4 positions.

Another major lost opportunity is the poor cooperation in securing infrastructure to connect the region to the wider transatlantic community. This also undermines the V4’s ability to jointly attract foreign direct investment and co-development projects.

One of the factors discouraging cooperation is that Europe has probably seen the peak of the benefits of EU integration. Further political consolidation is neither beneficial nor likely. Effective regional cooperation of some sort, therefore, will be an increasingly important competitive tool for countries to continue developing their economies and to attract and build human capital. The lack of an effective V4 puts the region at a disadvantage.

Scenarios

Unlikely: V4 countries geopolitically align

The most significant shift that could revitalize the V4 format is a change in national governments. The prospects for a less-EU skeptic grouping are low: The current government in Budapest may prevail in elections next year and the recent Czech elections resulted in a populist-leaning parliamentary majority. Meanwhile, the center-left governing coalition in Poland looks increasingly fragile and snap elections could well return a more center-right government. Yet even if more pro-EU governments took office in all four countries, that would still not lead to a revitalization of the V4, since all the administrations would be more inclined to focus their efforts on Brussels.

The V4 could become a more potent and influential European political bloc if populist-leaning governments dominated in all four countries and there was closer political union across Europe from the center-right to the populists. That change, however, requires political realignments that transcend the V4 borders.

Even if more populist governments did lead V4 countries, greater geopolitical alignment would not necessarily be the result, as both Russia and China will continue to exert influence in attempts to sow divisions in Central Europe.

While all four countries enjoy constructive relations with Washington, it is not likely the U.S. would invest much effort in trying to drive alignment among the V4. The current U.S. administration favors bilateral engagement and cooperation with minilateral formats. That said, if the V4 wanted to engage the U.S. more deeply as a group, that initiative would have to come from the countries themselves – which seems unlikely at the present.

Likely: Poland will focus its engagement on Baltic and Nordic countries

Regardless of the nature of future Polish governments and V4 developments, Warsaw is more likely to prioritize minilateral efforts to expand cooperation with the Baltic and Nordic states, consolidating the security and economic links of NATO’s northern flank with Central Europe.

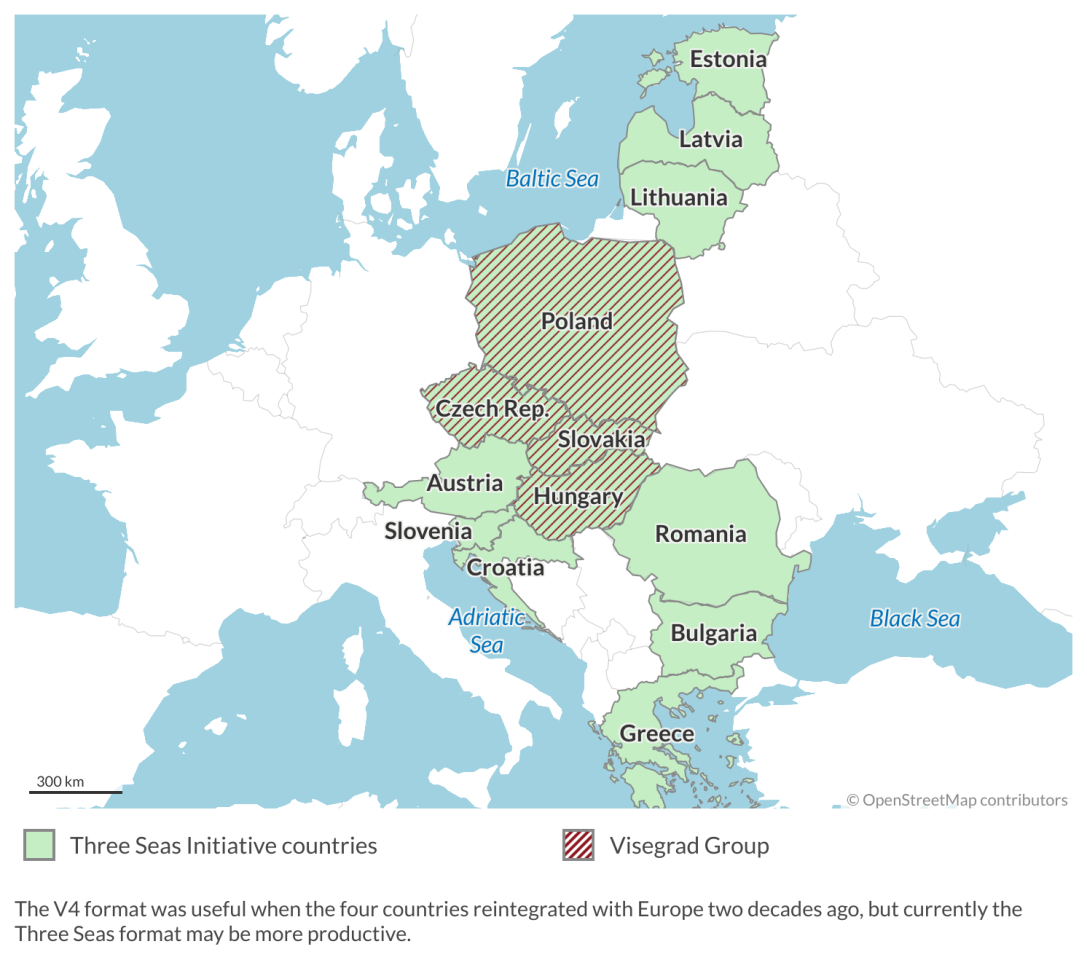

Likely: A broader Central European approach will trump a narrower V4

Other sectoral initiatives are likely to drive minilateral cooperation more prominently than the V4. The construction of the TSMC plant in Dresden, Germany, could be the impetus for a European “chip triangle,” linking German manufacturing capacity with the Czech Republic’s tech design and the Polish gas, chemical, testing and packaging industries. Romania is becoming a more central economic and security actor in the region. For regional groupings to be effective in establishing economic, digital and energy connectivity, Budapest will be an increasingly important player. Thus, from an economic perspective, there is no practical regional minilateral format without a broader V4+ approach.

Perhaps the most promising minilateral format for the V4 could be the Three Seas Initiative (3SI), which looks to bridge infrastructure, energy and digital connectivity from the high north through Central Europe and the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. This is an initiative that could play an instrumental role in the reconstruction of Ukraine and the continued integration of Moldova with the West. That said, a revitalized 3SI will require proactive leadership from the current country holding the presidency, Croatia, as well more enthusiastic support from Poland and partnership with the U.S. and Germany.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.