A few weeks ago, the Trump administration announced that they were planning on opening offshore areas for oil and gas leasing off the California coast. This is the first time in 40 years (since 1984) that new leases have been proposed offshore California. Trump attempted this same action in 2018 but ran into so much opposition that he abandoned these plans the next year. Public and political response this time was immediate and widespread at local and state levels to this recent announcement.

Perhaps understood by most Californians, the state controls use of the coastline and the waters out to 3 miles offshore, whereas the federal government has control beyond 3 miles. This is why the planned wind farm leases off Morro Bay and Humboldt Bay have been put on hold for now as Trump has essentially shut down all offshore wind energy projects, while at the same time he has ordered retired inefficient and uneconomical coal fired power plants to reopen, despite their high costs to consumers and their polluting emissions.

What limited information was contained in the administration’s announcement indicated that portions of the seafloor off Southern California, which extends from San Diego north to Big Sur, would be open for leasing in 2027, 2029 and 2030; for central California, which extends north from Big Sur to the northern Sonoma County line, leasing would occur in 2027 and 2029; and the Northern California offshore area, extending from Mendocino County to the Oregon border, in 2029. This information was contained in a report obtained by the Houston Chronicle and reviewed by the San Francisco Chronicle. Since Trump will no longer be president after 2028, planned leases in 2028 and 2029 may not happen.

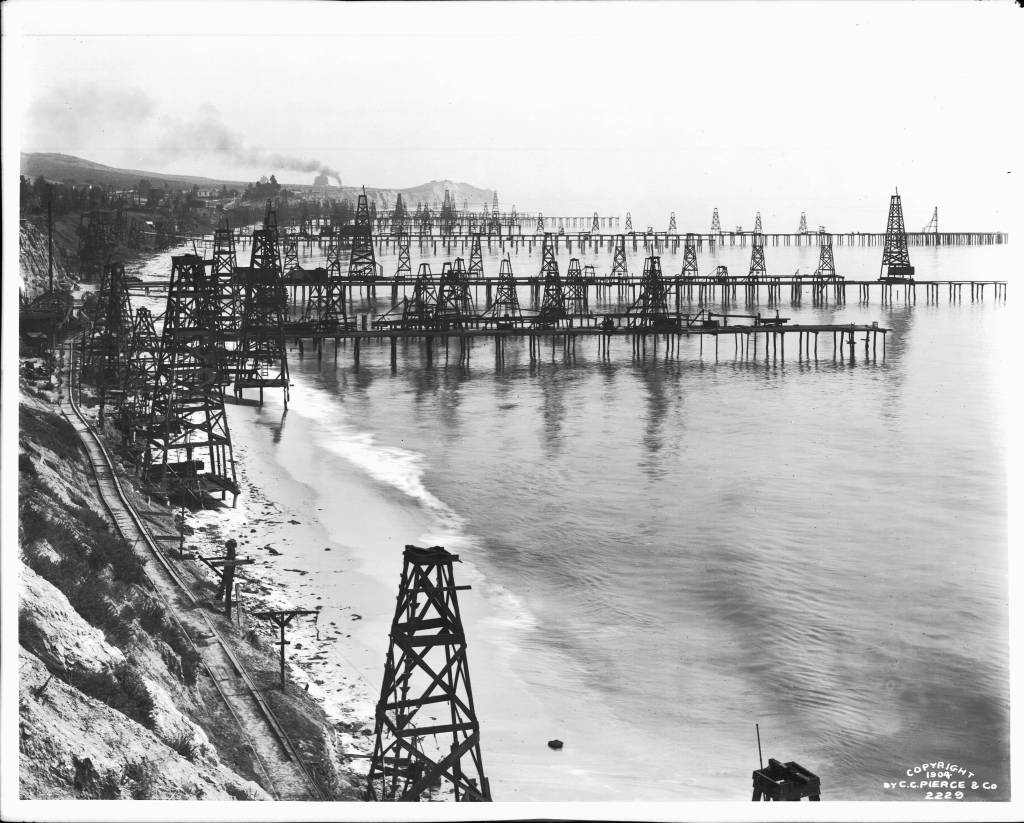

That are significant oil and gas reservoirs off southern California and they have been exploited for well over a century. Offshore recovery actually began in 1896 when piers were extended offshore for drilling south of Santa Barbara in the Summerland area. The first true offshore platform was installed in state waters in 1956 in the Santa Barbara Channel. Today there are 23 active oil platforms extending along the Southern California coast extending from Oceanside in the south to north of Point Conception in Santa Barbara County. However, many of these are nearing or have passed their expected lifespan, which presents some challenges regarding what we are going to do with these retired platforms, which is still being debated.

Moving north to Central California, the prospects of significant oil and gas are significantly reduced, however. Announcing that any offshore area is going to be put on the lease block for oil and gas doesn’t necessarily indicate there are substantial petroleum reserves present, however. Why and how oil forms were the topics of my first two Ocean Backyard columns back in April and May 2008, now 17 years ago.

There is clear evidence for hydrocarbons along the Santa Cruz County coast, however. Perhaps best known are the oil-saturated tar sands, also known as rock asphalt, within the Santa Cruz Mudstone, a sedimentary rock that underlies the coast from the west side of the city north to Año Nuevo. They occur as sedimentary intrusions and they were actively mined for years at several quarries along the north coast and in Bonny Doon.

The first paved roads built in the world were made of rock asphalt and Paris reportedly paved its first street with this material in 1854. Not to be outdone, in 1872 Union Square in New York City became the first street paved in the United States with rock asphalt brought all the way from Switzerland. Two decades later in 1891, Salt Lake City paved its first street with asphalt brought from Santa Cruz. The 1890s also saw asphalt from the Santa Cruz quarries shipped to San Francisco and Seattle to pave their roads.

An 1894-96 report from the California Mining Bureau described asphalt beds located up the coast between Majors and Baldwin creeks on Rancho Refugio:

“About six miles northwest of Santa Cruz and near the ocean are extensive beds of bituminous rock, which at present are being successfully quarried and utilized for making pavement. In fact, it is regarded by those in a position to know best that bitumen is the pavement of the future, and in the beautiful city of Santa Cruz it is the pavement of the present. These beds of bituminous rocks cover an area of perhaps a mile square and are the residuum of oil beds in a period not geologically remote … It is in the head of a canyon on the Baldwin Ranch, 5 miles northwest from Santa Cruz and 2 miles from the coast at 500 feet elevation. A good road has been made from the mine to the county road on the coast.”

This area was known at various times as the Asphalt Beds, the Petroleum Works and later the Baldwin Mine. Driving north on Highway 1, about 5 miles from the city limits, you can glance up Majors Creek Canyon on the inland side of the highway, and see massive steep black cliffs, which are composed of bitumen saturated sandstone or rock asphalt. A large portion of those cliffs collapsed in a massive landslide in 1960, damming Majors Creek and forming a small lake. A few hundred yards further along Highway 1, a turn off the left takes you through the little community of Majors, which used to have a small school known as the Petroleum School.

The asphalt content of these sandstones varies from about 4% to as much as 16% by weight, and some of these asphaltic beds are up to 40 feet thick. An estimated 614,000 tons of asphaltic paving material, worth approximately $2.36 million was produced from the area of the north coast between 1888 and 1914. Production was intermittent after the 1920s, with the last of the quarries ceasing operations in the 1940s.

The presence of this natural asphalt along the north coast, and the discovery of oil in the Signal Hill area of Long Beach in Southern California in 1921 (which incidentally brought my mother’s family to Southern California from Port Angeles, Washington, in the 1920s), led to the drilling of a number of wells along the north coast terraces in 1901. While fortunes were envisioned, the amounts of oil recovered were small.

In 1955, Husky Oil Co. in partnership with the Swedish Oil Shale Co., began an experimental project using gas-fired burners inserted into shallow wells in the asphaltic sands to liquefy and extract petroleum. Over a three-year period, 228 burner-producer wells were drilled on the terraces, raising down-hole temperatures to 600 degrees Fahrenheit. About 2,665 barrels of oil were recovered. While this was a reasonable recovery rate, fuel costs and high heat losses made this an uneconomical project, and it was terminated. There is more to this story to come.

Gary Griggs is a distinguished professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz. He can be reached at griggs@ucsc.edu. For past Ocean Backyard columns, visit seymourcenter.ucsc.edu/ouroceanbackyard.