Ludovica Ambrosino, Jenny Chan and Silvana Tenreyro

Macroeconomic Environment Theme

The Bank of England Agenda for Research (BEAR) sets the key areas for new research at the Bank over the coming years. This post is an example of issues considered under the Macroeconomic Environment Theme which focuses on the changing inflation dynamics and unfolding structural change faced by monetary policy makers.

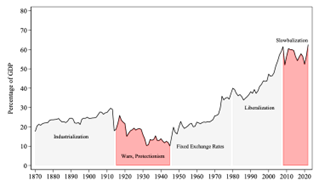

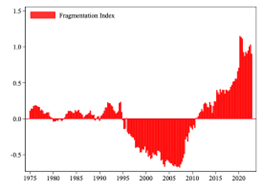

Global economic trends have changed markedly over the past two decades. The global financial crisis represented a turning point, with trade openness plateauing and fragmentation steadily increasing before rising sharply during the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Trade fragmentation is increasingly driven by national security concerns, the rise of ‘friendshoring‘, and the emergence of competing trade blocs. For policymakers, this raises a central question: how will trade fragmentation shape inflation dynamics, and what are the implications for monetary policy? A recent paper addresses this question by analysing trade fragmentation in a model where the inflationary effects depend on the adjustment of demand alongside supply.

Chart 1: Sum of exports and imports, per cent of GDP

Sources: Jorda-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory Database, Penn World Table, Peterson Institute for International Economics, OWID and World Bank.

Chart 2: Fragmentation has increased since the global financial crisis

Source: Fernandez-Villaverde, Mineyama and Song (2024). The index is normalised to 0, with positive (negative) values indicating increased (decreased) fragmentation.

A widespread view holds that trade fragmentation will be inflationary. As economies retreat from global integration and supply chains duplicate, production costs are expected to rise, exerting upward pressure on prices (Lagarde (2024); Goodhart and Pradhan (2020)). This perspective draws on the ‘tailwind from the East‘ narrative: the integration of low-cost producers into the global economy in the 1990s and 2000s helped keep tradable goods prices low, allowing advanced economies to sustain higher demand without breaching inflation targets. In the UK, for example, Carney (2017) noted that between 1997 and 2017 core goods prices fell by 0.3% a year on average, while services prices rose by 3.4%, leaving overall CPI inflation close to target over that period. Bank of England research further showed that the rising share of imports from emerging markets lowered UK import price inflation by around 0.5 percentage points per year between 1999 and 2011. Similar results have been documented elsewhere, including France. Against this backdrop, it would appear natural to expect that the reversal of globalisation could turn a long-standing disinflationary tailwind into a headwind.

However, the connection between global trade integration and disinflation is not as clear-cut as it might seem. Other structural forces, such as the widespread adoption of inflation-targeting regimes and prolonged periods at the effective lower bound also contributed to the disinflationary trends of recent decades. Moreover, the conventional view emphasises the direct supply-side effects of fragmentation, through higher marginal costs and import prices, while abstracting from the general-equilibrium consequences operating through lower real incomes and aggregate demand. If fragmentation reduces household purchasing power and weakens consumption, it may lower inflation rather than raise it.

This raises the question of whether, and under what conditions, demand-side effects might dominate the inflationary pressures originating from the supply side. To explore these competing dynamics systematically, we develop a two-sector, small open-economy New Keynesian model with household heterogeneity and imperfect international risk-sharing. Fragmentation is modelled through two channels: (i) a permanent increase in import prices, for instance due to tariffs or a shift toward more costly but geopolitically aligned suppliers; and (ii) a decline in tradable sector productivity relative to its long-run trend. This framework allows us to capture both the direct cost-push effects on supply and the indirect demand effects that operate through real incomes and consumption.

We analyse three stylised fragmentation scenarios.

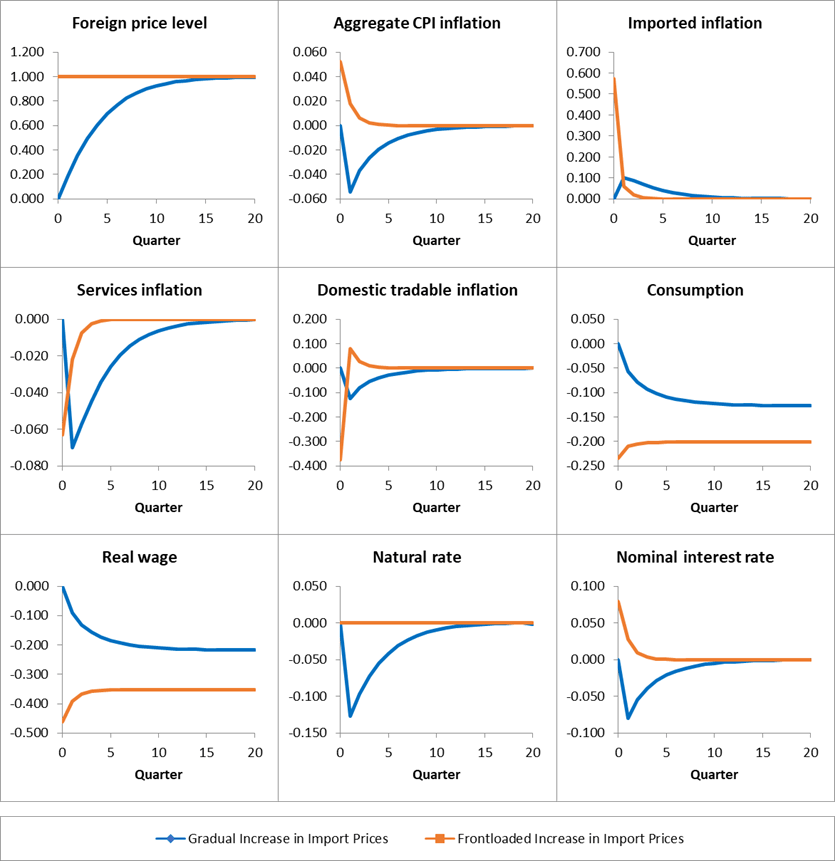

First, to simulate a gradual shift toward a more restrictive trade environment, Chart 3 shows the impulse responses to a gradual and permanent increase in import prices (blue lines). In this scenario, import prices stabilise at a permanently higher level in the medium term. The price of imported goods affects demand directly, both through the consumption basket and through imported inputs in services production. Additionally, it indirectly affects demand through real wages. Imported inflation rises, but this effect is outweighed by falling domestic inflation, as weaker current and anticipated real incomes reduce consumption and demand. Households partially offset lower wages by supplying more labour, mitigating supply constraints. On balance, aggregate CPI inflation falls, the natural real rate of interest declines, and monetary policy eases under a Taylor-type rule.

Next, Chart 3 also illustrates the impact of a permanent, front-loaded rise in foreign import prices (orange lines). The shock leads to a sharp but temporary spike in imported inflation, driving up CPI inflation, while consumption falls and stabilises at a lower level. Inflation in the service sector and the domestic tradable sector decline with weaker demand, but imported inflation dominates. The economy experiences a temporary bout of stagflation, while the natural real rate remains unchanged. Under the Taylor rule, the central bank raises the policy rate to return inflation to target. Policymakers face a trade-off in this scenario: a front-loaded rise in import prices creates a temporary inflation overshoot even as demand contracts. Stabilising inflation requires tighter policy in the short run, at the cost of weaker output and consumption.

Chart 3: Gradual versus frontloaded increase in import prices

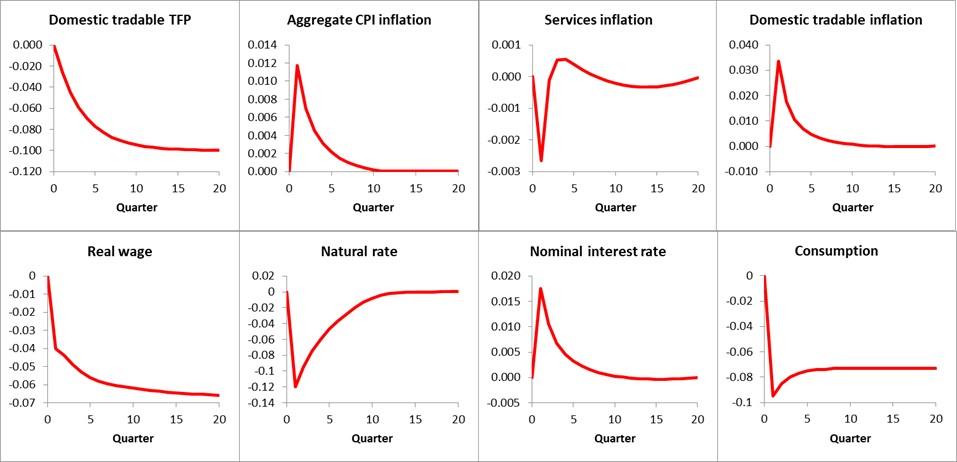

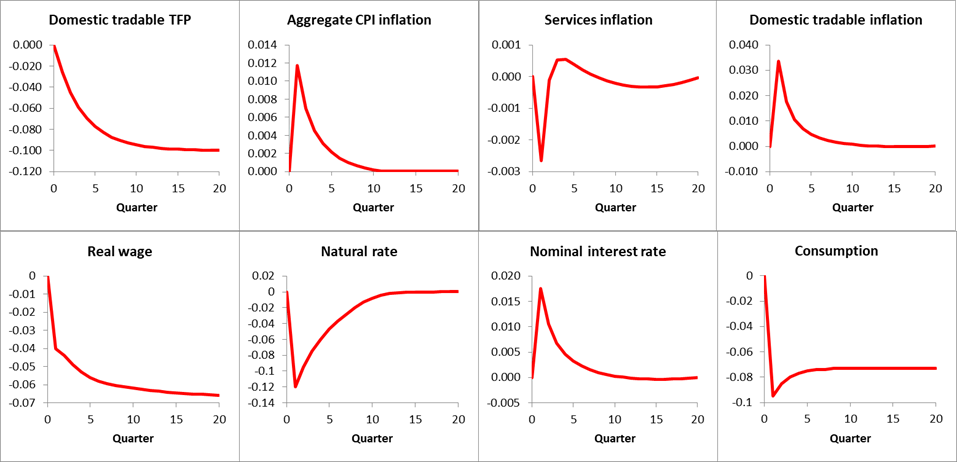

Finally, we consider a fragmentation shock in the form of a permanent and gradual decline in tradable-sector productivity, shown in Chart 4. Lower productivity raises marginal costs, requiring more labour per unit of output and pushing up tradable inflation. Real wages do not fall as much as in the import price scenarios, limiting the contraction in demand. The modest fall in service sector inflation is insufficient to offset higher tradable inflation, so aggregate CPI inflation rises. Monetary policy responds with a temporary tightening to bring inflation back to target, while the natural rate falls before gradually returning to steady state.

Chart 4: Gradual shock to productivity in the domestic tradable sector

To summarise, across all three scenarios, fragmentation represents a shock that contracts supply, but its net impact on inflation depends on how demand adjusts. In the gradual fragmentation case, permanently higher import prices reduce real incomes and consumption, leading to stagnation with disinflationary pressures, consistent with the type of fragmentation the economy experienced in the period between the global financial crisis and just before the pandemic. A front-loaded, permanent shock creates a short-term policy trade-off, with weaker activity alongside higher CPI inflationary pressures, consistent with the experience during the pandemic and the large increase in energy and commodity prices caused by the war. A permanent decline in tradable-sector productivity has an ambiguous effect in theory but is moderately inflationary in our calibration. Taken together, these results show that the inflationary consequences of fragmentation depend on how it materialises and the extent to which it is anticipated.

Robustness and extensions

Trade openness

To understand the underlying mechanisms, we also vary the initial degree of trade openness. More open economies are more directly exposed to foreign price shocks. In the scenarios involving permanent increases in foreign prices, whether gradual or front-loaded, the more open economy experiences a larger decline in the natural rate of interest. All the results we discussed in the previous sections are exacerbated in more open economies. However, in the case of a negative TFP shock, output falls more in a closed economy, as more open economies can mitigate the impact by diversifying away from domestic shocks through trade.

Greater dependence on imported inputs in production

Our results across the three scenarios are also robust to additional domestic supply-side constraints. When production uses a higher share of imported inputs, import price increases place tighter constraints on domestic supply. Factor substitution towards labour leads to an increase in employment, leaving demand dynamics largely unchanged. Greater dependence on imported inputs therefore does not alter the results qualitatively. As the demand side continues to be driven by falling real wages, higher labour supply, and weaker consumption, the gradual scenario still produces disinflation and stagnation, while the front-loaded shock generates a policy trade-off as weaker demand fails to offset surging tradables inflation. The adverse TFP shock remains moderately inflationary, though less so, as greater reliance on imported inputs in services production reduces this sector’s capacity to absorb labour, lowering marginal costs and dampening aggregate CPI inflation.

Nominal rigidities

Our extension with nominal wage rigidities lead to more moderate disinflation in the gradual fragmentation case and more persistent inflation in the front-loaded case. While wage stickiness moderates the fall in real wages, it also leads to a fall in labour demand. The demand-side effect of our various shocks are therefore preserved, as real wages fall more moderately but employment falls more steeply. Relatedly, allowing prices to adjust more frequently increases disinflationary pressures in the gradual scenario, while reducing the trade-off for policymakers in the front-loaded case.

Substitutability of consumption goods

Finally, increased substitutability between domestic and foreign tradables, and lower substitutability between tradables and services mitigates the impact of the adverse terms-of-trade shock. This specification seems to matter most for the gradual scenario, where it leads to less stagnation relative to the baseline calibration.

Conclusion

The shift from trade integration to fragmentation marks a turning point for the global economy. The key takeaway is that trade fragmentation does not mechanically imply stronger inflation or the need for tighter policy. Its impact is theoretically ambiguous, as the form in which fragmentation materialises will affect the balance of supply and demand. Depending on how shocks unfold, the extent to which they are anticipated, and how households and firms adjust, fragmentation may lead to stagflation in the case of front-loaded shocks, stagnation with disinflation when shocks are gradual and anticipated, or moderate inflation when productivity deteriorates. This can help reconcile competing views: those focusing on persistent supply constraints see upside risks to inflation, while those emphasising demand adjustment anticipate stagnation and scope for easing.

Ludovica Ambrosino is a PhD student at London Business School, Jenny Chan works in the Bank’s Research Hub Division and Silvana Tenreyro is the James E. Meade Professor of Economics at the LSE.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “Trade fragmentation and inflationary pressures”