It’s no secret that China, Japan, and Germany are industrial powerhouses, with vast potential in clean tech manufacturing. So how’s a less industrialized nation with an eye on the economy of the future supposed to compete? Are protectionist policies such as tariffs a good way to jumpstart domestic manufacturing? Should it focus on subsidizing factory buildouts? Or does the whole game come down to GDP?

According to a new machine learning tool from Johns Hopkins’ Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab, none of the above really matters all that much. Many of the policies that dominate geopolitical conversations aren’t strongly correlated with a country’s relative industrial potential, according to the model. The same goes for country-specific characteristics such as population, percentage of industry as a share of GDP, and foreign direct investment, a.k.a. FDI. What does count? A nation’s established industrial capabilities, and the degree to which they cross over to climate tech.

The purpose of the tool, named the Clean Industrial Capabilities Explorer, is to help policymakers “X-ray your country’s existing industrial base to identify what are your genuine strengths,” Tim Sahay, co-director of the lab, told me. The model, he explained, can identify “which core capabilities in your underlying industrial know-how are weak. That is like a diagnosis of what you should get into.”

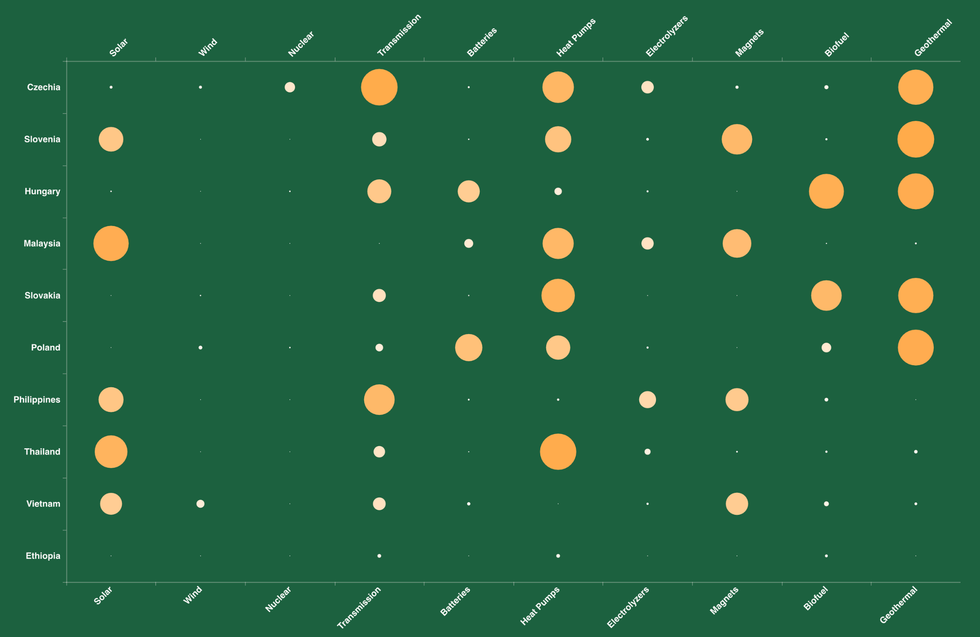

The model calculates competitiveness across 10 clean energy technologies: solar, wind, batteries, electrolyzers, heat pumps, permanent magnets, nuclear, biofuels, geothermal, and transmission. That analysis ultimately surfaced five “core capabilities” that are most predictive of a country’s relative strength in each technology area: electronics, industrial materials, machinery, chemicals, and metals. Strength in geothermal, for example, is highly correlated with a machinery-focused industrial base, since building a geothermal plant requires expertise in making drilling rigs, heat exchangers, and steam turbines.

This “X-ray” of national capabilities not only confirms the dominance of leading Asian and European manufacturing economies, it also surfaces a group of lesser-known nations that appear well-positioned to become major future producers and exporters of key clean technologies. These so-called “future stars” include a handful of Central European countries — Czechia, Slovenia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland — plus the Southeast Asian economies of Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. In Africa, Ethiopia emerges as the most promising economy.

Take Hungary as an example — its core competencies are machinery, electronics, and chemicals, making the country highly competitive when it comes to producing components for batteries, biofuels, and the machinery critical for geothermal power plants. The U.S., by comparison, excels at nuclear, electrolyzers, biofuel, and geothermal.

Many of the European future stars appear to benefit from their proximity to Germany, long an industrial stronghold in the region. “Poland, for example, received a huge amount of German FDI in the late 90s, early 2000s,” Sahay told me, explaining that countries in this region built up strength in their chemicals and metals sectors under the influence of the Soviet Union. Germany then set up these countries as key suppliers for its various industries, from autos to chemicals.

Of the 10 countries identified as rising stars, all of them received Chinese investment sometime in the past 10 years, Sahay said. “What we are seeing is decisions that have been made over the last couple of decades are bearing fruit in the 2020s,” he said, explaining that all of the countries on the list “were identified as places for potential investment by the world’s leading industrial firms in the 2000s or 2010s.”

This has led Bentley Allan, a political science professor and co-director of the policy lab, to think that China is likely doing some modeling of its own to determine where to direct its investments. Whatever the country is working with, it’s arriving at essentially the same conclusions regarding which nations show strong industrial potential, and are thus attractive targets for investment. “China isn’t the only one who can benefit from that strategy, but they’re the only ones being strategic about it at the moment,” Allan told me.

Allan’s hope is that the tool will democratize the knowledge that’s helped China dominate the global clean tech economy. “No one’s produced a global tool that enables not just China to invest strategically, but enables the U.S. to invest strategically, enables the UK to invest strategically in the developing world,” he explained. That’s critical when figuring out how to build an industrial base that can weather geopolitical tensions that might necessitate, say, a shift away from Chinese imports or Russian gas.

While it might not be particularly surprising that a country’s existing industrial capabilities strongly correlate with its potential industrial capabilities, the reality is that in many cases, getting a clear view of a country’s actual core competencies is not so straightforward. That’s because, as Allan told me, economists simply haven’t made widely available tools like this before. “They’ve made other tools for managing the macroeconomic environment, because for 60 years we basically thought that that was the only lever worth pulling,” he said.

Due to that opacity around industrial strength, model was able to yield some findings that the researchers found genuinely surprising. For example, not only did the tool show that countries such as the Philippines and Malaysia have stronger manufacturing bases than Allan would have guessed, it ranked Italy higher than Germany in overall competitiveness, showing solid potential in the nuclear, transmission, heat pump, electrolyzer, and geothermal industries.

That illustrates another complication the model solves for — namely that the countries with the most potential aren’t always the ones pursuing the most robust or intentional green industrial strategies. Both Italy and Japan, for instance, are well-positioned to benefit from a more explicit, structured focus on climate tech manufacturing, Allan told me.

Industrial strength will likely not be achieved through broad economic policies such as tariffs, subsidies, or grant programs, however, according to the model. Say for example that a country wants to deepen its expertise in solar manufacturing. “The things that you might want to invest in are things like precision machinery to produce the cutters that actually are used to cut the polysilicon into wafers,” Allan told me. “It’s more about making targeted investments in your industrial base in order to produce highly competitive niches as a way to then make you more competitive in that final product.”

This approach prevents countries from simply serving as final assemblers of battery packs or solar panels or other green products — a stage that provides low value-add, as countries aren’t able to capture the benefits of domestic research and development, engineering expertise, or intellectual property. Pinpointing strategic niches also helps countries avoid wasting their money in buzzy industries where they’re simply not competitive.

“The industrial policy race is very much hype-driven. It’s very much driven by, oh my god, we need a hydrogen strategy, and, oh my god, we need a lithium strategy,” Sahay told me. “But that’s not necessarily going to be what your country is going to be good at.” By pointing countries towards the industries and links in the supply chain where they actually could excel, Sahay and Allan can demonstrate they stand to benefit from the clean energy transition at large.

Or to put it more broadly, when done correctly, “industrial policy is climate policy, in the sense that when you advance industry generally, you are actually advancing the climate,” Allan told me. “And climate policy is industrial policy, because when you are trying to advance the climate, you advance the industrial base.”