Also in this week’s edition: How five tariff-exposed industries in Canada are faring

Alberta’s MoU adds to Washington’s heavy-oil dilemma

By Shaz Merwat, Energy Policy Lead

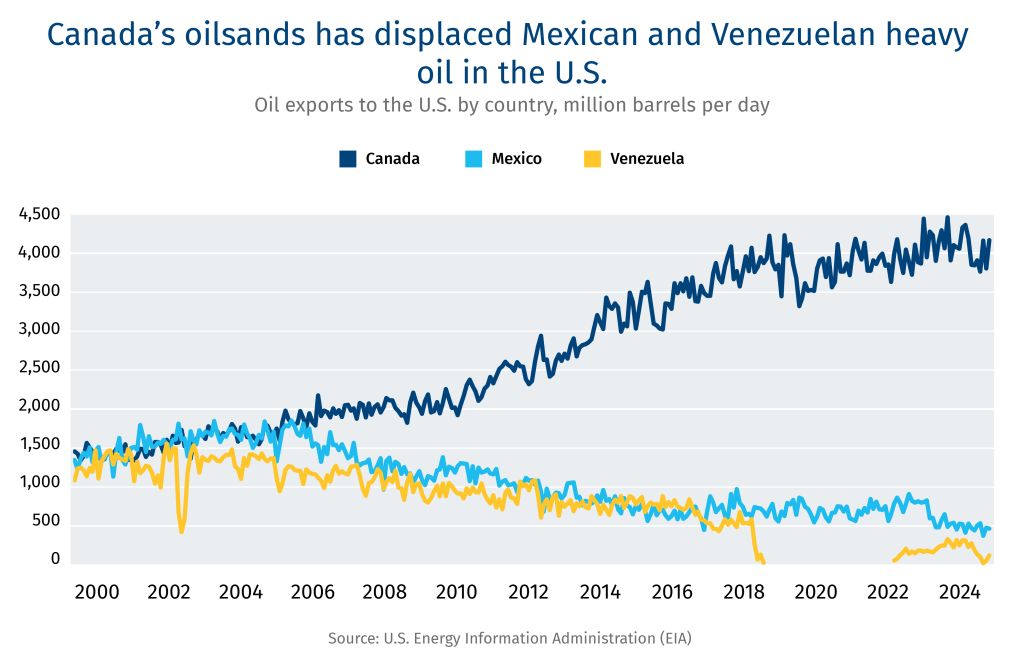

As U.S. President Donald Trump hosted Prime Minister Mark Carney and Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum, energy issues loomed in the background amid U.S. concerns about structural deficits in heavy crude. Historically, Canadian barrels competed with Venezuelan heavy crude in key U.S. refining markets—primarily the U.S. Midwest and the Gulf Coast. While Venezuelan volumes have been largely absent for the past decade, shifting U.S. foreign-policy signals suggest that competition could re-emerge.

Why it matters — Trump cannot unwind two core U.S. dependencies

Despite efforts to reshape U.S. supply chains, Washington remains structurally dependent on two things it cannot easily substitute: Canadian heavy crude and Chinese rare earths. Heavy crude is foundational to U.S. refining capacity, and as it stands, the U.S. cannot easily replace Canadian supply: domestic production is overwhelmingly light, and heavy-crude alternatives from Mexico and Venezuela have structurally declined.

These twin constraints limit U.S. leverage and elevate the importance of stable, long-term supply partners. Alberta’s Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) arrives at a moment when U.S. policymakers must balance geopolitical objectives—such as renewed attention on Venezuela—with the reality that Canadian barrels remain irreplaceable in the refinery system.

By the numbers — the heavy-barrel shortfall

Mexico: U.S. bound heavy-crude exports have fallen from as high as ~1.7 mb/d in 2005-2006 to roughly ~0.40 mb/d today.

Venezuela: heavy-crude exports to the U.S. surpassed 1.5 mb/d in the early 2000s; today U.S. exports are ~0.1 mb/d.

Canada: The dominant exporter to the U.S., with around four million barrels of crude shipped south of the border daily. The Canada-Alberta MoU proposed 1 million bpd pipeline, plus 300,000–400,000 bpd from Trans Mountain together create a sizeable uplift in export capacity—primarily oriented toward Asia.

The bigger picture — if Venezuela returns, does Canada lose leverage?

A Venezuelan “return” would likely be slow, expensive and politically fragile. Refinery contracts, debt obligations and upstream infrastructure all require rebuilding. Even under a regime change, investors will demand decade-long stability before committing capital.

Mexico faces similar limits: Sheinbaum inherits state-owned Pemex’s declining production and mounting debt, meaning a rapid restoration of heavy-crude exports is unlikely.

This leaves Canada as the only credible, scalable source of heavy supply. The MoU’s accelerated timelines—carbon-pricing equivalency, methane rules and Pathways carbon capture, utilization and storage project—signal Ottawa and Edmonton are preparing for sustained output growth.

Bottom line — the MoU prepares Canada for a more competitive heavy-oil landscape

As Canada builds westward capacity through TMX and the proposed 1 million bpd pipeline, more barrels are positioned for Asia rather than the U.S. That shift inevitably forces U.S. policymakers to consider how they will secure heavy-crude supply in the coming decade—including whether to re-engage Venezuela in a more meaningful way.

For Canada, today, this is less of a challenge. The MoU ensures that, regardless of how U.S. policy evolves, producers have diversified market access and greater resilience. If Venezuelan volumes rise, Canada will have optionality; if they do not, Canada remains the primary supplier to U.S. refiners.

Either way, the middle of the next decade is shaping up to be a far more dynamic heavy-oil environment—and the MoU positions Canada to navigate it from a position of strength.