Get We Are The Mighty’s Weekly Newsletter

Military culture and entertainment direct to your inbox with zero chance of a ‘Reply All’ incident

On Oct. 5, 1986, a cargo plane running a covert resupply mission to the Nicaraguan Contras was shot down by Sandinista forces. The lone survivor, Vietnam veteran Eugene Hasenfus, promptly told the world he’d been working on a CIA-linked airlift, exposing the secret effort to support the Contras despite a Congressional ban on funding the right-wing rebel group.

Related: How shoddy email practices led to the convictions in the Iran-Contra Affair

Hasenfus’ ordeal would be the catalyst in revealing a deeply complicated and highly illegal arms sales scheme that threatened (for a time) to topple the administration of President Ronald Reagan. The Associated Press reported this week that Hasenfus died of cancer on Nov. 26, after a nine-year struggle with cancer. He was 84 years old.

Eugene Hasenfus being escorted by guards during his trial. (Cindy Karp/Getty Images)

Eugene Hasenfus being escorted by guards during his trial. (Cindy Karp/Getty Images)

Three other crew members were killed in the crash, but Hasenfus had parachuted into the jungle, where he evaded capture for more than a day. He was eventually tracked down and held by the Nicaraguan government on terrorism charges, among other crimes. But Hasenfus let the cat out of the bag, and Congress soon launched a full investigation into what became known as the Iran-Contra Affair.

The Reagan administration initially disavowed Hasenfus and his downed plane, claiming it had no connection to the United States government. Hasenfus, meanwhile, was convicted in Nicaragua and sentenced to 30 years in prison. He was eventually pardoned by Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega and sent home to Wisconsin. But while Hasenfus’ ordeal seemed to have ended, the Reagan Administration’s was just beginning.

Less than a month after Hasenfus’ CIA plane was downed in the jungle, another bombshell fell on Washington. On Nov. 3, 1986, the Lebanese magazine Ash-Shiraa reported that the United States had been secretly selling arms to Iran—officially an enemy, if you remember the 1979 capture of the U.S. embassy in Tehran—in exchange for hostages. American officials confirmed pieces of the story within days.

On Nov. 25, Attorney General Edwin Meese admitted that profits from those Iran arms sales had been diverted to fund the Contras, tying the two scandals together in one illegal Rube Goldberg machine. The Iran-Contra Affair was a sprawling, complex, choose-your-own-disaster scheme combining two operations that should never have met: covert support for right-wing rebels in Nicaragua and clandestine arms sales to Iran, which was officially an enemy state under a U.S. arms embargo.

On the Contras’ side, the administration wanted to back Nicaraguan rebels fighting the leftist Sandinista government, but Congress’ legal roadblocks restricted American support for the Contras. On the Iranian side, Reagan and his advisers were obsessed with freeing American hostages held by Hezbollah in Lebanon, a group linked to Iran’s government, and some officials also hoped to cultivate a friendlier Iranian faction for the long term. Out of this stew came a scheme: secretly sell arms to Iran using Israel as an intermediary, try to leverage those sales to free hostages, and skim the profits to fund the Nicaraguan Contras.

It was all totally off the books, because (again) it was all totally illegal.

President Reagan, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, Secretary of State George Shultz, Attorney General Ed Meese, and Chief of Staff Donald Regan trying to figure out what to tell the American people after they’d been caught. (National Archives)

President Reagan, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, Secretary of State George Shultz, Attorney General Ed Meese, and Chief of Staff Donald Regan trying to figure out what to tell the American people after they’d been caught. (National Archives)

The story actually began when Reagan took office in 1981, vowing to roll back communist influence in the Western Hemisphere. His administration quickly embraced the Contras in Nicaragua as freedom fighters and began covert support through the CIA. By 1982, Congress was getting nervous about human rights abuses and mission creep, so it passed the first Boland Amendment limiting U.S. involvement in efforts to overthrow the Nicaraguan government. A stricter version in 1984 essentially bans U.S. intelligence agencies from providing military support to the Contras.

Instead of backing off, however, key officials around National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane and his successor, Adm. John Poindexter, start looking for workarounds. The National Security Council’s Lt. Col. Oliver North helped build a network of foreign governments, private donors, and front companies to keep money and weapons flowing to the Contras despite Congressional restrictions.

In 1985, members of the administration were drawn into the idea—pushed by Israeli intermediaries and some U.S. officials—that selling arms to elements inside Iran could serve two purposes: help “moderate” forces gain influence and secure the release of American hostages held in Lebanon. Reagan signed off on a series of covert arms transfers, including TOW anti-tank missiles and HAWK anti-aircraft parts, even though Iran was under a U.S. arms embargo and labeled a state sponsor of terrorism.

The logic was that these were limited, controlled sales that might produce diplomatic leverage. In practice, hostage releases happen sporadically at best, and new kidnappings follow, making the whole thing look less like a clever strategy and more like paying ransom in installments.

Between 1985 and 1986, the two operations merged. North and others realize they can mark up the price of weapons sold to Iran and funnel the excess cash to support the Contras, effectively turning a hostage diplomacy scheme into a funding pipeline for a prohibited war, all without informing Congress, and in ways that arguably violate both U.S. law and the Constitution’s separation of powers.

It was all managed through a maze of shell companies and foreign cutouts, including a key role for retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Richard Secord and businessman Albert Hakim, who helped run the logistics and finances. Reagan himself was shielded by layers of plausible deniability, at least on the diversion of funds, even as he was directly involved in approving the general idea of arms sales to Iran.

President Reagan says it happened because he cared *too* much.

The whole thing crashed in 1986 with Eugene Hasenfus. By the end of that year, the focus shifted to damage control and reckoning. Reagan appointed the Tower Commission, an independent review board, which criticized the administration’s chaotic decision-making and the National Security Council’s freelancing. Congressional hearings turned Oliver North into a household name as he admitted to shredding documents and helping set up the diversion of funds, actions he claimed were patriotic.

Criminal charges were filed against several officials, including North, Poindexter, and former National Security Adviser McFarlane. Some were convicted, though many convictions are later overturned on appeal because their testimony to Congress had been immunized, and in 1992, President George H. W. Bush issued pardons to six Iran-Contra figures, effectively closing the legal chapter.

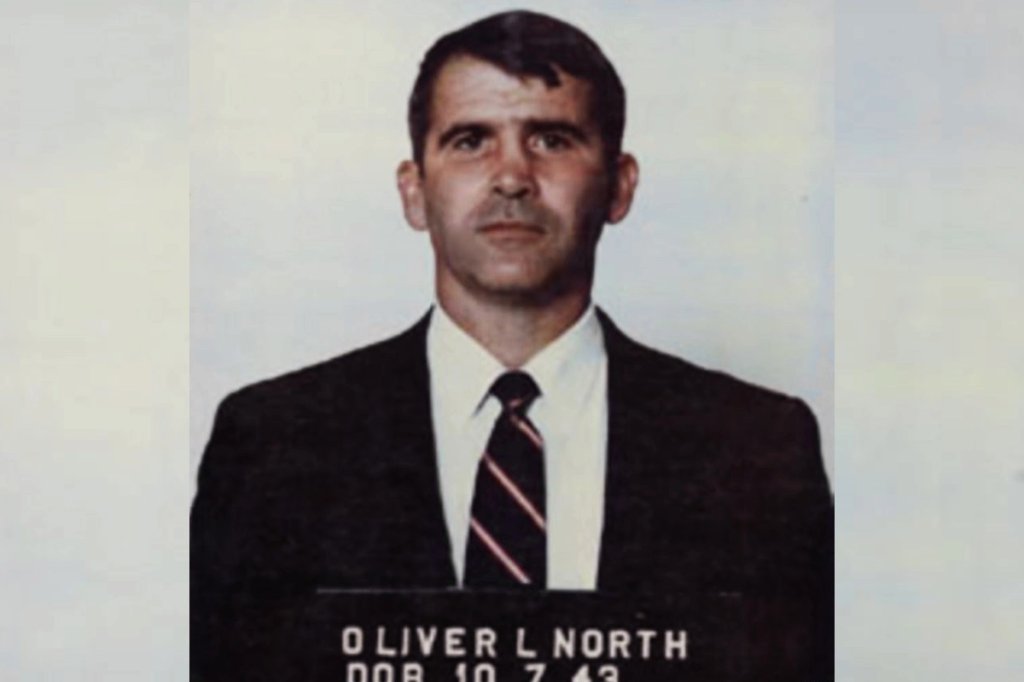

Oliver North’s mug shot. (Department of Defense)

Oliver North’s mug shot. (Department of Defense)

By the time the dust settled in the early 1990s, Iran-Contra had become a textbook case in how an administration can try to conduct foreign policy off the books, bypassing Congress with deniable networks and creative bookkeeping. No one went to prison for it, and Reagan’s approval ratings eventually recovered, but the scandal left a constitutional hangover, raising enduring questions about executive power, oversight, and how far officials will go when they’re convinced history will thank them later.

Hasenfus returned to Wisconsin by Dec. 18, 1986, where he slipped out of the headlines. He focused on his family and worked as an ironworker, deliberately avoiding the spotlight… for a time. In 1987, he filed a civil suit seeking about $135 million in damages from figures tied to the Contra supply network, and by 1990, he was also in court trying to recover the salary and hazardous duty pay he was owed for the time period around his capture.

Don’t Miss the Best of We Are The Mighty

• ‘Operation Underworld’ was a secret wartime pact no one saw coming

• How US troops quietly crushed Russian mercenaries in Syria

• The US plan to nuke its interstate highways into existence

‘Operation Underworld’ was a secret wartime pact no one saw coming

Blake Stilwell is a former combat cameraman and writer with degrees in Graphic Design, Television & Film, Journalism, Public Relations, International Relations, and Business Administration. His work has been featured on ABC News, HBO Sports, NBC, Military.com, Military Times, Recoil Magazine, Together We Served, and more. He is based in Ohio, but is often found elsewhere.