Marco Rubio lives two lives. His days begin at the State Department and end at the White House. He is the first figure since Henry Kissinger to hold the posts of national security adviser and secretary of state at the same time, two foreign policy jobs that once defined postwar Republicanism — but he serves in a presidency intent on dismantling much of that tradition.

Managing the demands is a challenge: colleagues say he often camps out at the president’s house until Donald Trump has gone to bed. His West Wing office is close to both Trump’s chief of staff, Susie Wiles (recently described by the president as “the most powerful woman anywhere”), and vice-president JD Vance.

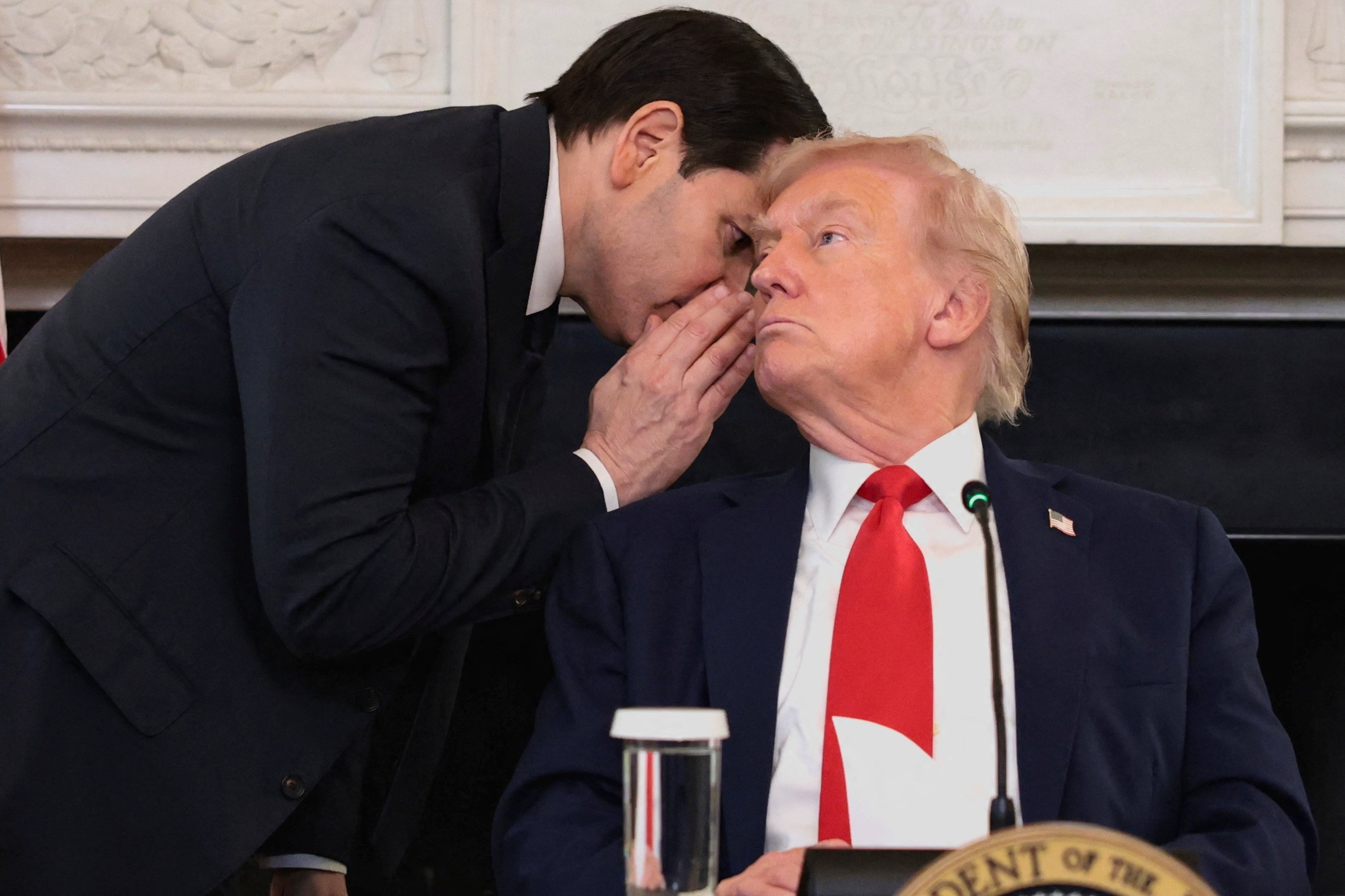

Rubio, colleagues note, has quickly learnt that when it comes to winning an argument or influencing a decision in this administration, proximity is key. Especially with a president accustomed to asking advice from anyone he walks past or picks up the phone to.

He has inserted himself into Trump’s inner orbit with an almost anthropological care, learning when to speak, when to nod and when to simply stay in the room. Increasingly he is a sounding board for the president (some say a sobering force), seen as a relative veteran who knows both raw politics and how the Senate and House work.

Trump has tipped Rubio as part of a joint ticket for 2028 with Vance. “Marco is my best friend in the administration,” the vice-president said recently. “A lot of the good work we do … is because we’re all able to work together.”

Rubio and JD Vance could run on the 2028 ticket

MARK SCHIEFELBEIN/AP

But as the US worldview fractures inside the administration itself — with the release last week of a new national security strategy setting out a foreign policy vision that focuses on America’s own backyard and questions whether certain nations in Europe, which it claims faces “civilisational erasure”, can remain reliable allies — Rubio’s true colours are a source of intrigue in Washington.

Is the former neoconservative hawk, a soundbite machine once mocked by Trump as “Macro Robotco”, now a reborn member of the Maga faithful, or is he quietly pursuing his own agenda? Is he the apprentice, the moderator or the old-school Republican sleeper?

With the stakes rising by the week, the question of which Rubio will emerge has become one of Washington’s most consequential unknowns.

Rubio defended Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign after being rivals in 2016

EVELYN HOCKSTEIN/REUTERS

‘How long will he keep going?’

To Rubio’s critics on the right, he is the neocon who never really changed. Last month Rubio had to deny he was on a different page to the administration after claims he had described the administration’s 28-point peace plan for Ukraine, drawn up by Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner, as a Russian wish list to a group of senators. Rubio was forced to deny this on social media as administration figures were quick to go on the offensive over the “fake news”. He later flew to Geneva and led talks that stripped out Moscow’s most egregious demands.

“I think that we’re all wondering if he’s having an out-of-body experience and how long he’ll keep going,” said Joel Rubin, a Democrat and former deputy assistant secretary of state for house affairs. “Marco had a little honest moment there with, like, ‘yeah, this is the Russians’ plan’, and then he freaked out. He’s like, ‘no, no, no. I mean, it was our plan. It was our plan.’”

Justin Logan, director of defence and foreign policy studies at the Cato Institute in Washington, said: “My understanding of Rubio, and I don’t believe this has changed, is he’s very much a sort of neoconservative. He has a view of the United States as being very active in the world, but he works for Donald Trump and so he is, I believe, pulling punches on many issues where he would prefer to be more forward-leaning, because he has to do what his boss tells him.”

Rubio’s past positions range from being a vocal supporter of USAid during his time as a senator (he has since overseen its dismantlement) and, in 2015, calling Vladimir Putin a “gangster and thug” (Trump’s Middle East envoy, Steve Witkoff, has said Putin is “not a bad guy”).

• Putin believes he’s winning his war on the West. He may be right

“I think he has had a genuine change of heart,” said Matthew Boyle, the bureau chief of the right-wing website Breitbart. “He went from being arguably the leading candidate for president in 2016 and Trump blew right past him. Since the 2016 election, and even in the lead-up to it, he has really questioned the people who led him astray.

“I’ve talked to him about this. He spent time in the Rust Belt learning from American workers and I think that made him a better person and a better politician. I don’t see neocon in there. I see a pretty realistic, pragmatist foreign policy that’s very in line with Trump and Vance.”

Matthew Boyle says of Rubio: “I don’t see neocon in there”

TOM BRENNER/REUTERS

On Friday the national security strategy sent shivers down the spines of European leaders. The 33-page document read like an angry continuation of Vance’s February Munich Security Conference speech, accusing European governments of sleepwalking towards “civilisational erasure” through immigration that would render their countries “unrecognisable”.

The authors ranged widely. As well as Rubio there was Michael Anton, a Trump ally and former state department official; Pete Hegseth, the secretary of war; and, importantly, Hegseth’s under-secretary for policy, Elbridge Colby, who was only confirmed by the Senate by 54 to 45 votes after opposition from hawks over his Iran dovishness and clashes with congressional Republicans. At a November hearing, the Republican senator Dan Sullivan complained “I can’t even get a response, and we’re on your team”, claiming it was harder to reach Colby than Hegseth or even Trump himself.

Several Nato allies, the document said, were being turned into majority “non-European” countries. In parts, it read like America serving divorce papers to Europe, lambasting allies for “censorship of free speech and suppression of political opposition, cratering birthrates and loss of national identities and self-confidence”.

Steve Bannon, the former White House strategist, said: “If I were a European head of state, I would be immediately calling in my top advisers and figuring out how we’re actually going to pay for our own national security because it shouldn’t be lost on anybody that the European peace plan starts on page 29. It is behind the western hemisphere, it is behind Asia.”

On Ukraine, the strategy berated “European officials who hold unrealistic expectations for the war”. The only crumb of comfort to Atlanticists was a phrase describing peace and Ukraine’s survival as a “core interest” of the White House. There was nothing about defending Ukraine’s territorial integrity or the principle of resisting aggression; only that it should remain a “viable state”.

Bannon saw this as pure Rubio. “I think you see his hands here in the paragraph about Ukraine being vital to American security interests. I don’t think anybody in the populist right believes that at all. We just want a complete pull-out of Ukraine.”

Surrounded by exiles

The son of Cuban immigrants and long seen as a prospective president, Rubio’s story attracts attention. He grew up in Miami surrounded by exiles from Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua. In his 2012 memoir, An American Son, he said this was where he developed his worldview — including deep opposition to socialism — as “it is impossible to be apolitical in a community of exiles”.

He rose up the ranks of Floridian politics quickly, although later faced flak over the timing of his parents’ move to America. In his early telling of his origin story, Rubio implied that they fled Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution, but it later transpired they left three years before, in 1956. He was accused of embellishing and later admitted to “getting a few dates wrong”, but said the main themes held true: being forced out by communism and moving to America for opportunity.

Rubio was elected to the Florida House of Representatives in early 2000, appointed House majority leader two years later and joined the Senate in 2011. He ran for the Republican nomination in 2016 but had to drop out after a disappointing showing in his home state.

During that attempt, he pitched himself as a new-generation conservative, but was dogged by his past, more moderate positions on immigration. In 2013 he was part of the “gang of eight”, a bipartisan group that drafted comprehensive immigration reform, including a path to citizenship (amnesty), which failed.

Learning the lessons

“I always say there are two people who learnt the right lessons from getting the shit beat out of them by Trump in 2016,” Boyle said. “They’re Marco Rubio and [talk show host] Megyn Kelly. What did the two of them do? Went and did the work, learnt what they did wrong and made themselves better. That’s all that anybody out there in the base wants to see happen.”

Megyn Kelly endorsed Trump’s presidential campaign last year after clashing with him in 2016

BRIAN SNYDER/REUTERS

There’s been much talk in the media that Rubio is being sidelined, with the biggest briefs being handled by Witkoff, Kushner and Vance. But there is another theory doing the rounds. “He’s positioned himself as the good guy,” said a DC veteran with links to the administration. “Why is he not going to Nato’s conference? Rather than deal with the nasty conversations, send the deputy.”

What’s more, there is one area where Rubio is not only aligned with Maga, but is a key architect: the western hemisphere. Last week’s strategy paper made the shift explicit, listing the hemisphere first of the regions and arguing for retrenchment elsewhere in order to concentrate power in America’s backyard.

As Rubio himself put it in an interview: “I would say, if you’re focused on America and ‘America First,’ you start with your own hemisphere. What happens in our hemisphere impacts us faster and more deeply than something that’s happening halfway around the world.”

This sentiment has led to a more interventionist approach by Trump, from trying to oust Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro to pardons for conservative leaders (Trump pardoned Honduras’s former president Juan Orlando Hernández for his US drug trafficking conviction in a move that puzzled and outraged House Republicans, given the White House’s efforts to stop the illicit trade), tariffs for left-wing leaders and bailouts for libertarians.

“Trump is a personalist leader,” Logan says. “He’s a transactional leader and so he frequently views these discrete cases as being about friends and enemies. The discourse around the bail-out was very much, you know, he’s on our side in Latin America.”

• Gerard Baker: Drug pardon shows Trump losing his touch

So Rubio is part of a wider effort to clean the western hemisphere of dictators and narcotics. On this, Rubio and Vance are aligned, even if they come to it with different perspectives: Rubio as a child of Miami, Vance for stopping the influx of narcotics that he has seen change towns like the one he grew up in.

“For Rubio, the western hemisphere policy is personal — between his own family story and representing Florida, which has had hundreds of thousands of migrants come out of Cuba and Venezuela,” says a figure close to the administration.

In Florida it is also a voter issue. Many in the community have fled communist policies and see it as a key issue, even if it is unlikely to translate to wider America. Administration figures also hope the idea of hitting cartel boats will translate into an anti-drug message that reaches middle America.

Rubio has survived by adapting, by absorbing Trump’s blows in 2016 and learning how to navigate the movement that replaced the party he once hoped to lead. But adaptation has its limits. If the intellectual energy of the American right now lies with Anton, Colby and Vance, Rubio risks being overtaken by a worldview far more inward-looking, seeing Nato as a burden and Europe as a liability.

This is precisely why some in European capitals have begun to see Rubio not just as a go-between but as their last sympathetic conduit in a White House turning away from them and a party that, after Trump, could take an even more hardline approach to “America First”.

Trump may talk up a joint ticket, but the ideological centre of gravity is shifting. The question is what does Rubio stand for when the president is not in the room — and how far is he willing to risk holding the bridge between Europe and America?