A team of Bulgarian researchers has made an exceptional discovery in a Copper Age necropolis: the remains of a young man who survived the attack of a large felid, most likely a lion, and who was then cared for by his community for a long period. The study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, combines bone evidence, forensic analysis, and archaeological context to narrate a story of survival and social solidarity in the prehistory of the Balkans.

The story begins near the present-day Bulgarian coast of the Black Sea, in a place known as the Kozareva mound. There, archaeologists excavated a late Eneolithic (Chalcolithic) necropolis dating to the 5th millennium BCE. Among the tombs, number 59 held a striking secret.

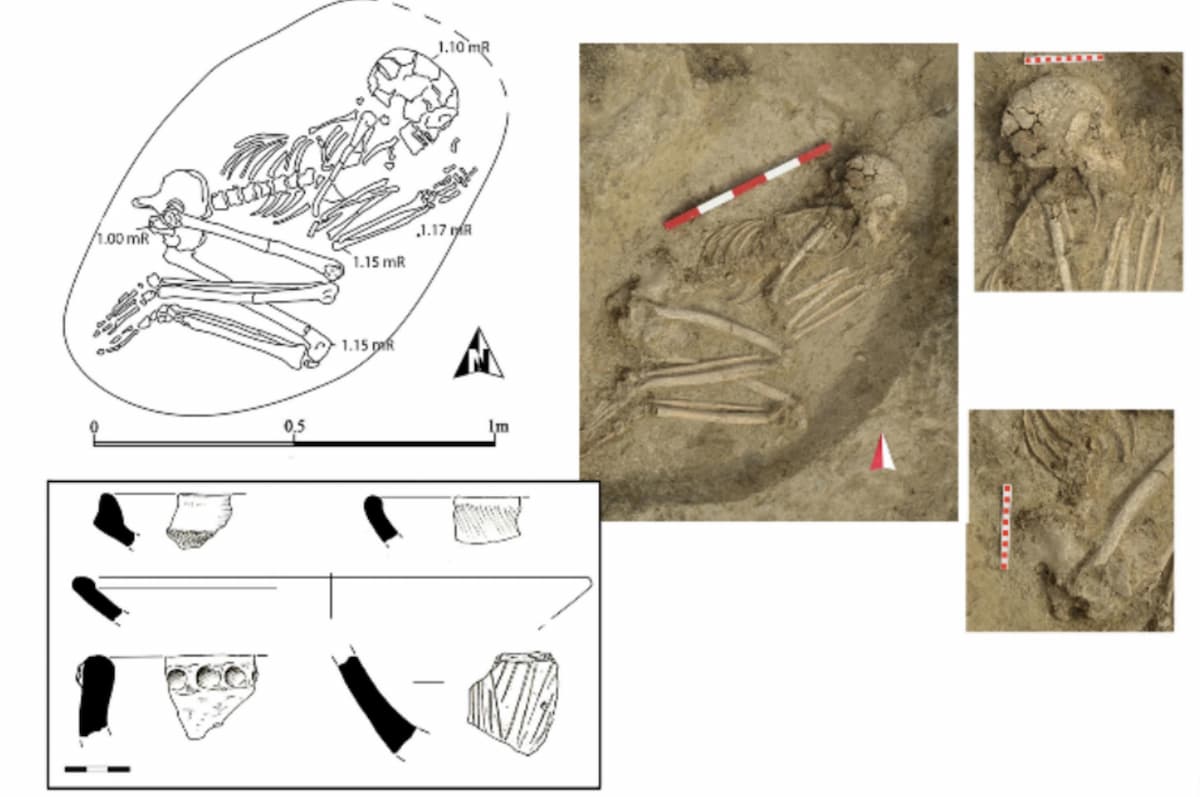

The skeleton, belonging to a young male between 18–20 and 30 years of age, was found in a flexed position on his left side, without grave goods. His height was notable for the time, estimated between 171 and 177 cm. But what immediately caught the scientists’ attention were the unusual marks on his bones.

The discovery in the Kozareva Mogila necropolis, Bulgaria. Credit: N. Karastoyanova et al. 2026

The discovery in the Kozareva Mogila necropolis, Bulgaria. Credit: N. Karastoyanova et al. 2026

The wounds that tell a story

The detailed examination of the remains, although fragmented, revealed a pattern of trauma that was both devastating and, at the same time, hopeful. The most dramatic evidence was found on the skull. It presented three main lesions. Two of them, on both parietals (the bones on the sides of the head), near the coronal suture, were small depressions or pits.

The third, on the left parietal, was much more severe: an irregular opening measuring about 22 × 19.5 millimeters that completely pierced the cranial cavity, reaching the brain. Inside the skull, a splintered bone fragment had fused to the internal surface.

The marks were not limited to the skull. The left fibula (calf bone) showed a deep depression. The right fibula displayed a cluster of small pits. Additionally, bone reactions were observed on the left clavicle and humerus, possible indicators of severe muscular or tendon injuries.

The crucial finding was not just the presence of these wounds, but their condition. All of them showed clear signs of antemortem healing, meaning they occurred long before the individual’s death. The fracture edges were covered with a well-developed bone “callus,” with no evidence of active infection at the time of death.

The researchers estimate that the injuries occurred at least two or three months before his death, and even suggest, based on the degree of bone ossification, that the penetrating cranial trauma may have occurred when the young man was between 10 and 18 years old.

Receive our news and articles in your email for free. You can also support us with a monthly subscription and receive exclusive content.

The attacker: The trace of the lion

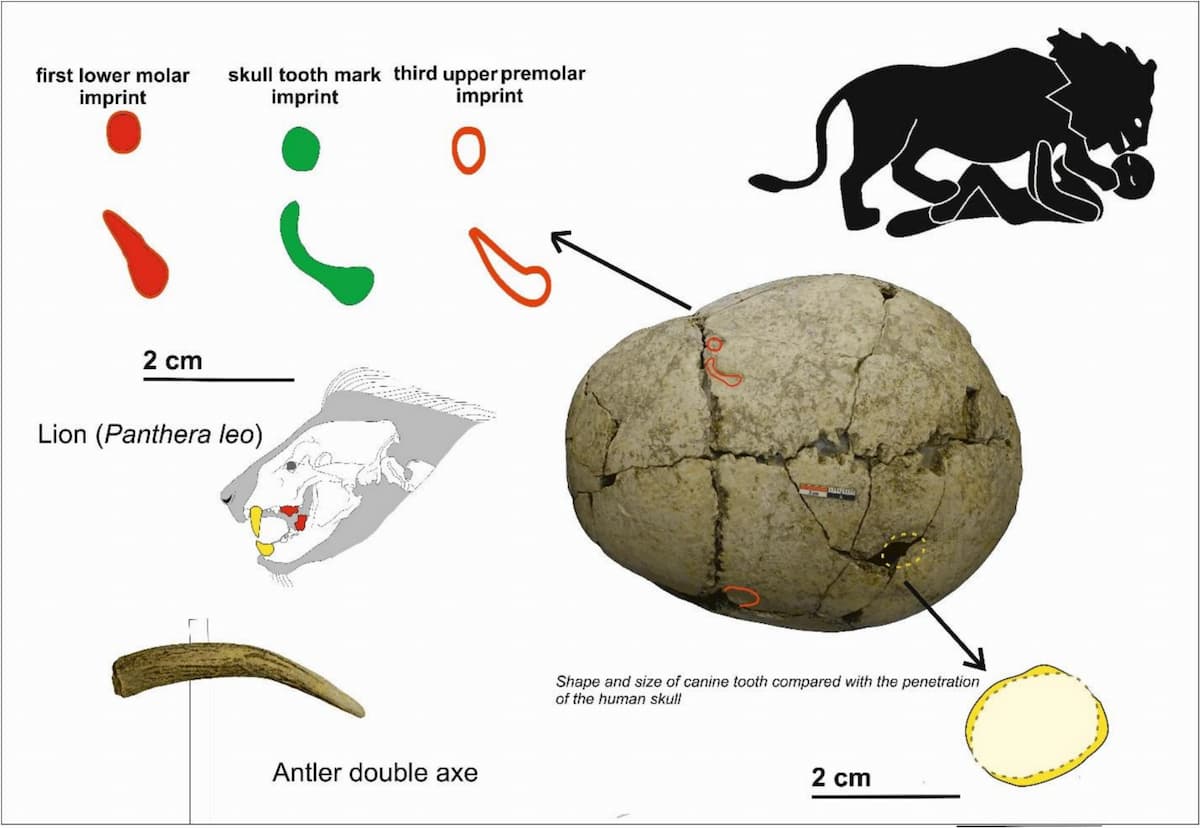

The obvious question was: what or who caused these wounds? The scientists ruled out several possibilities. The shape and location of the injuries did not match those of known tools or weapons from the time, such as antler axes. Nor did they align with evidence of interpersonal violence typical of the period, or with intentional manipulation or trepanations.

They then focused their investigation on a possible animal attack. Using high-precision silicone molds, they compared the marks on the skull with the teeth of large carnivores. The result was revealing.

The small pit on the right parietal showed an irregular shape that matched almost perfectly that of a superior carnassial tooth (third premolar) of a lion (Panthera leo). The penetrating opening on the left parietal, due to its oval shape and size, was consistent with the wound a canine tooth of a large predator could inflict. The measurements and depth of the marks, up to 5 mm, ruled out smaller felines such as the lynx or leopard (whose remains in the region are much older, from the Pleistocene).

Location and shape of the pit marks on the skull compared with left carnassial teeth − third premolar (upper), first molar (lower) and antler double axe. Suggested attack according to the bite of the lion and skull marks. Credit: N. Karastoyanova et al. 2026

Location and shape of the pit marks on the skull compared with left carnassial teeth − third premolar (upper), first molar (lower) and antler double axe. Suggested attack according to the bite of the lion and skull marks. Credit: N. Karastoyanova et al. 2026

The archaeozoological analysis of the marks on the skull, in comparison with the teeth of large predators, shows that in terms of shape and size, they most closely resemble the superior carnassial teeth of a lion, the article concludes. It adds: This allows us to hypothesize that the young individual was attacked by a lion and survived with severe injuries and long-lasting effects on both his physical and psychological condition.

Reconstructing the attack: a prehistoric scene

Based on the injuries and the behavior of large felines, the researchers propose a plausible scenario. The lion, likely in a surprise attack from behind or over the shoulder—a common tactic to bring down prey—bit and clawed the young man’s head. One of its premolars left a mark on the right side of the skull, while a canine forcefully penetrated the left side, splintering the bone inward. The leg and arm injuries could be the result of deep scratches, bites, or the struggle during the attack.

Surviving such an assault in an era without modern medicine is, in itself, astonishing. But the study goes further: the advanced healing of the wounds is indirect evidence that the young man received prolonged care.

The injuries, especially the open cranial perforation and limb wounds that certainly affected muscles and tendons, implied a high degree of disability. He may also have needed support to walk short distances in daily life, the researchers note. Survival and recovery, however limited, would not have been possible without the active help of his group.

His survival and the healing of his injuries suggest that he was attended to and treated… he lived and was cared for by the community, indicating that they looked after their disabled members, the report emphasizes. This aspect places the discovery within the framework of “bioarchaeology of care,” which studies how past societies tended to their sick and injured, reflecting a cooperative social structure.

The story, however, contains an intriguing nuance. Despite these lifetime cares, his burial displays characteristics that invite reflection. The tomb, although relatively deep (a trait sometimes associated with certain status), lacked any grave goods, unlike others in the necropolis. Moreover, it was located in a sector dominated by the burials of adolescents and subadults, also without grave goods.

The authors propose two not mutually exclusive interpretations. On one hand, his permanent disability may have kept him in a low social position, similar to that of younger individuals, reflected in a burial without items. On the other hand, his physical appearance—with deep facial and bodily scars—and his possible neurological or behavioral sequelae may have caused him to be perceived as a “dangerous deceased” or a special figure in ritual terms, which could explain the depth of the grave. The study cites ethnographic parallels in traditional cultures, where extraordinary physical marks sometimes carry ambivalent social perceptions, clarifying that a direct cultural continuity is not suggested, but rather a recurring human pattern.

Implications of the discovery

This exceptional case offers a unique window into multiple aspects of life in Eneolithic Bulgaria. It confirms the presence and danger of the lion in the region, a predator whose remains, though rare, appear in sites of the period.

It provides one of the clearest and oldest osteological evidences of a lion attack on a human in which the victim survived. It is tangible proof of compassion and community care. It demonstrates that this 5th-millennium BCE society invested resources and attention in supporting a severely disabled member for months or years, prioritizing group well-being over immediate individual productivity.

And it allows us to trace the “osteobiography” of a particular person: a tall young man who suffered nutritional deficiencies or childhood illnesses (evidenced in his teeth and eye sockets), who survived a traumatic encounter with the most fearsome predator in his environment, and who, thanks to his people, lived to tell the tale, carrying the marks of the experience to his grave.

Ultimately, the skeleton from tomb 59 at Kozareva Mogila ceases to be a collection of ancient bones and becomes the silent yet eloquent testimony of a day of prehistoric horror and, above all, of the many days of human solidarity that followed.

Nadezhda Karastoyanova, Victoria Russeva, Petya Georgieva, Veselin Danov, Bones, bites, and burials: investigating a skeleton from eneolithic necropolis for evidence of probable lion attack in Bulgaria. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 69, February 2026, 105526. doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105526