Editor’s note: Writer Sasha Abramsky, who wrote a

photo essay on Sacramento’s Afghan community

last year, checked in with his sources and other community

members for their reactions to the suspension of asylum cases for

Afghans.

The day before Thanksgiving, a 29-year-old man named Rahmanullah Lakanwal shot two National

Guard members from West Virginia who were involved in the

Trump-ordered military patrol of Washington, D.C. Both guard

members were critically injured; one, Sarah Beckstrom, died of

her injuries shortly after.

Lakanwal had reportedly

worked with the

CIA during the

United States’ 20-year engagement in Afghanistan. He was allowed

into the U.S. in 2021 after the Taliban regained control in the

country and received asylum status in the early

months of the Trump presidency.

In the immediate aftermath of

the killing, allpending asylum cases were put on hold. All

Afghans trying to get visas to come into the U.S. were told their

visa applications would not be processed. All immigration and

green card hearings for residents of 19 countries put on a

“travel ban” list were cancelled, and the administration

announced it would re-examine all asylum, green card and other

visa statuses gained by Afghans living in the U.S. since

2021.

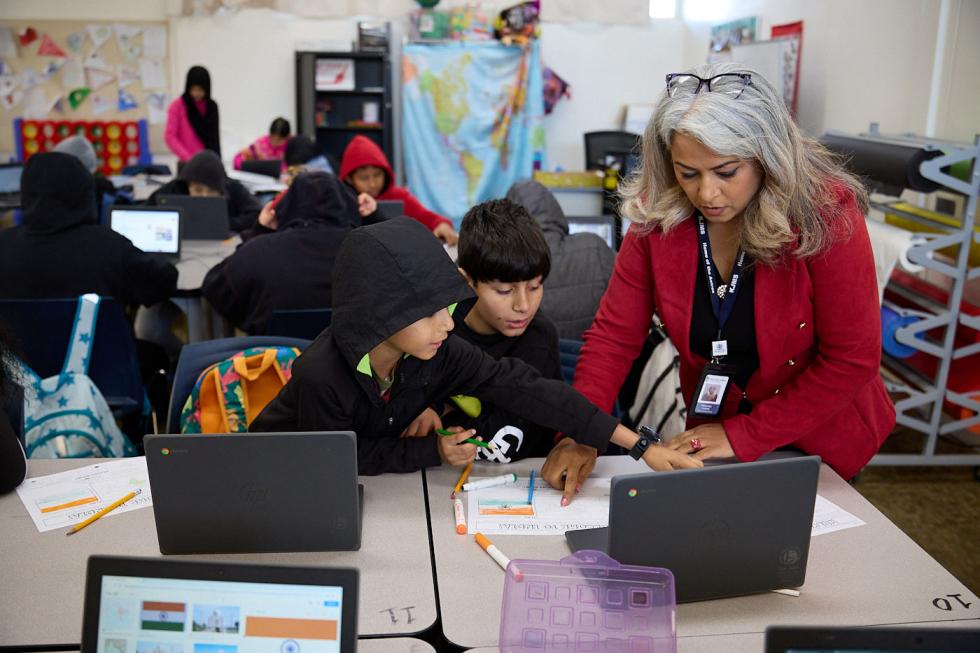

Middle school girls, including Maryam (center), daughter of

Afghan artist Aziz Tokhi, study at home in Sacramento.

Overnight, hundreds of

thousands of men, women, and children had their status thrown

into jeopardy. Thousands of them live in the Sacramento region,

one of the top relocation destinations for Afghans and home to

the country’s largest Afghan American community, according to

the

Migration Policy

Institute. Many of

the adults who have fought with, or otherwise aided, the U.S. and

its allies in Afghanistan are at risk of torture or execution

should they be returned to that country.

“It shouldn’t be generalized,”

says Zaki Raihan, owner of the Lapis Grill, a Carmichael

restaurant that serves Afghan cuisine. “In every nation, every

country, there are people with mental issues. … We should not

associate that with a religion, a tribe, a nationality.” Raihan

says that he, personally, isn’t scared, but he increasingly

worries that “we live in a country where we are dealing with ICE.

They assume everyone and every immigrant are bad people.”

Zaki Rahain works in the food truck associated with his

Carmichael restaurant, Lapis Grill.

Farzana Karimi, a woman who

came to the U.S. on a special immigrant visa after working with

U.S. forces for five years, and who now has U.S. citizenship,

agrees with this sentiment. “The person who commits the crime is

solely responsible for it; not his family, community, ethnicity,

language group, religion. Personal responsibility is one of the

central pillars of justice systems around the world,” she

says.

Several other Sacramento-area

Afghans spoken to for this article didn’t want their names used.

“There is a lot of fear and anxiety, and a greater sense of

collective punishment by the government toward the Afghan

community,” one man said. “This community helped the U.S. in

their war in Afghanistan. That’s why they’re here. In Sacramento,

the families are fearful to go outside. It’s difficult to take

their children to the park.”

The suspension of asylum

processing “is a major blow to the community. They feel betrayed

by the administration,” he continued. “I have family members

here, my kids, siblings with asylum cases pending. There’s

uncertainty here for people who have applied for asylum. And

people with green cards and approved asylum cases are afraid of

being reevaluated and deported.”

Abdul Basir, a lawyer now helping fellow Afghans resettle in

Sacramento, helps a boy choose a donated winter coat.

He told Comstock’s that the

reason his family was in the U.S. was because they had been vocal

in their criticism of what the Taliban was doing, including the

group’s abysmal human rights record and removal of girls’ access

to education. “Yesterday,” he says, “they hanged a person in

public. That’s the situation in Afghanistan — especially for

people who backed the U.S.” And, now, he felt, the net was

closing in in the U.S. as well.

“You cannot do anything. If

you raise your voice, you’ll be labeled by the administration.

It’s a very terrible situation to be in,” he says. “I love

America. I have been here for the last 10 years. My kids go to

school, my wife to college. I have a job. A community should not

be punished for an individual’s act.”

Another local Afghan-born

resident, who worked with U.S. forces in a psych-ops task force

in Afghanistan, bitterly reflected on the irony of working to

root out terrorists in Afghanistan only to now be labeled a

potential terrorist and criminal by the current administration

because of the acts of another person.

“This is something unfair,” he

says. “When a person is committing a crime, it is totally and

only a personal event. The government is trying to punish people

collectively. This is, I believe, against humanity. I worked with

U.S. forces, came to this country legally, was vetted by lots of

organizations in Afghanistan. I was polygraphed three times while

working with U.S. forces. I am asking President Trump to not

generalize and single out a whole community.”

–

Subscribe to the

Comstock’s newsletter today.