A chip smaller than a human hair may be the missing link to truly scalable quantum computers.

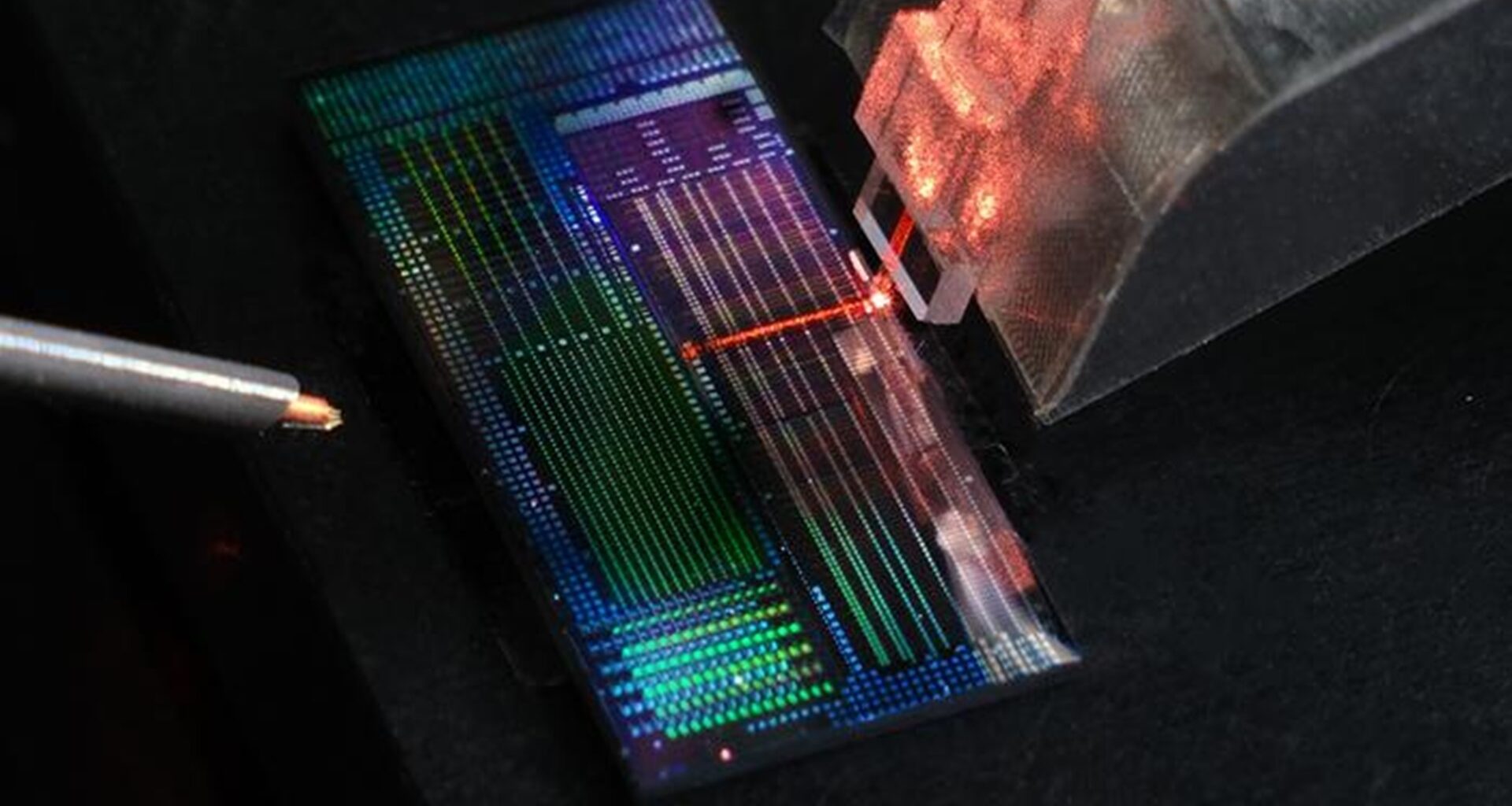

Researchers have unveiled a new optical phase modulator that is nearly 100 times smaller than the width of a human hair, and it could finally unlock the massive qubit counts needed for next-generation quantum machines.

The advance is built for scale. Instead of relying on bulky, custom hardware, the team created a device manufactured using the same processes behind everyday microelectronics: the chips inside computers, phones, cars, and even toasters.

Led by Jake Freedman, incoming PhD student in the Department of Electrical, Computer, and Energy Engineering; Matt Eichenfield, professor and the Karl Gustafson Endowed Chair in Quantum Engineering; and collaborators from Sandia National Laboratories, including co-senior author Nils Otterstrom, the team built a device that is tiny, powerful, and—crucially—mass-producible.

Their modulator uses microwave-frequency vibrations, oscillating billions of times per second, to manipulate laser light with remarkable precision.

Laser control breakthrough

These ultra-fast vibrations allow researchers to directly control a laser’s phase and generate new frequencies with high stability and efficiency—functions essential for quantum computing, sensing, and networking.

Among the leading quantum architectures are trapped-ion and trapped-neutral-atom systems.

These qubits store information in individual atoms, which must be addressed using laser beams tuned with extraordinary accuracy.

“Creating new copies of a laser with very exact differences in frequency is one of the most important tools for working with atom- and ion-based quantum computers,” Freedman said. “But to do that at scale, you need technology that can efficiently generate those new frequencies.”

Today’s frequency-shifting systems rely on large table-top setups that consume heavy microwave power—fine for lab demos, but impossible to scale to the hundreds of thousands of optical channels future quantum computers will require.

“You’re not going to build a quantum computer with 100,000 bulk electro-optic modulators sitting in a warehouse full of optical tables,” Eichenfield said.

“You need some much more scalable ways to manufacture them…”

The new device solves that. It consumes roughly 80 times less microwave power than many commercial modulators and produces new frequencies of light through efficient phase modulation.

Lower power means less heat, allowing many more channels to sit side by side—even on a single microchip.

Fab-made for scale

One of the most important elements of the breakthrough is how it’s made: entirely in a semiconductor foundry.

“CMOS fabrication is the most scalable technology humans have ever invented,” Eichenfield said. “So, by using CMOS fabrication, in the future, we can produce thousands or even millions of identical versions of our photonic devices…”

According to Otterstrom, the team has taken devices that were “previously expensive and power hungry” and made them far more efficient and compact. “We’re helping to push optics into its own ‘transistor revolution,” he said.

Next, the researchers are building integrated photonic circuits that combine frequency generation, filtering, and pulse-carving on the same chip.

“This device is one of the final pieces of the puzzle,” Freedman said. “We’re getting close to a truly scalable photonic platform capable of controlling very large numbers of qubits.”

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy through the Quantum Systems Accelerator program.

The study appears in the journal Nature Communications.