At the heart of every camera is a sensor, whether that sensor is a collection of light-detecting pixels or a strip of 35-millimeter film. But what happens when you want to take a picture of something so small that the sensor itself has to shrink down to sizes that cause the sensor’s performance to crater?

Now, Northeastern University researchers have made a breakthrough discovery in sensing technologies that allows them to detect objects as small as individual proteins or single cancer cells, without the additional need to scale down the sensor. Their breakthrough uses guided acoustic waves and specialized states of matter to achieve great precision within very small parameters.

The device, which is about the size of a belt buckle, opens up possibilities for sensing at both the nano and quantum scales, with repercussions for everything from quantum computing to precision medicine.

Shrinking cameras

Previously, when a scientist wanted to train a camera on something very small, the camera itself had to reduce in size, too. As camera systems shrink, however, the technology comes up against greater and greater barriers, according to Cristian Cassella, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern.

A specialist in microelectromechanical technology, that is, electrical and mechanical systems that operate on scales often smaller than the width of a human hair, Cassella says that as the size of the pixels in the camera sensor decreases, performance and sensitivity both degrade. So how, Cassella wondered, “can you get an equivalent reduction of the pixel size without reducing the pixel size?”

While this might seem like a contradiction in terms, it forced Cassella to think outside the box, eventually approaching collaborator Marco Colangelo, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern. Colangelo, Cassella and Siddhartha Ghosh, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering who also contributed to the project, all share laboratory space in Northeastern’s EXP building.

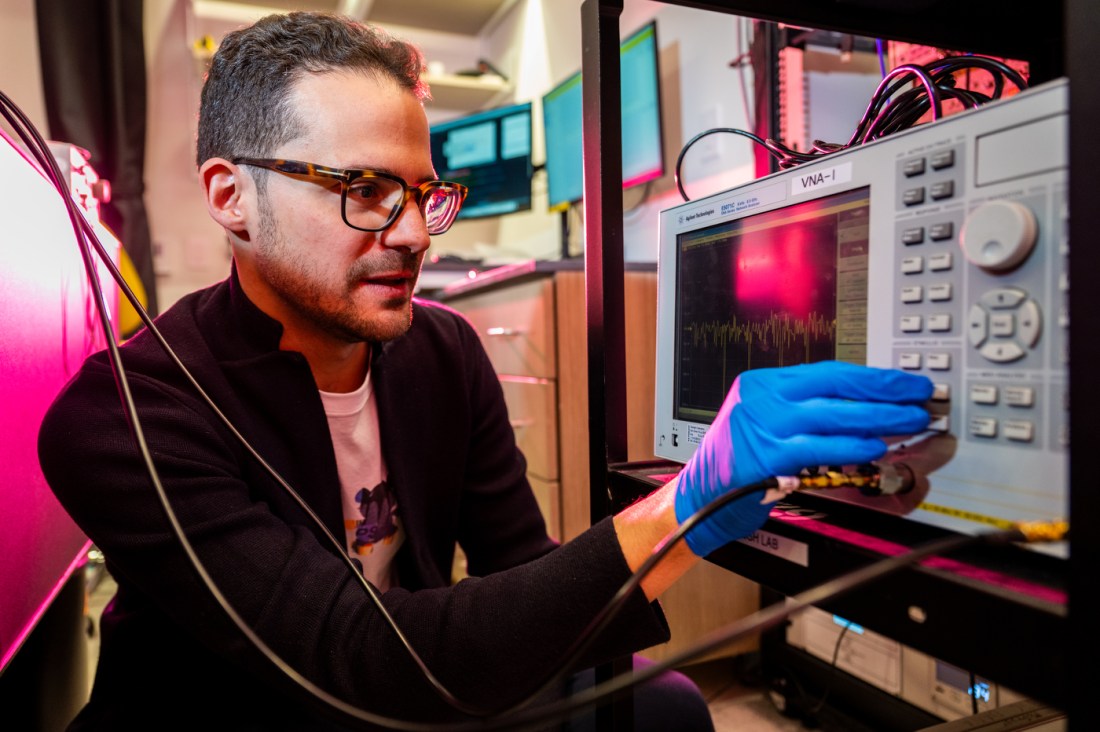

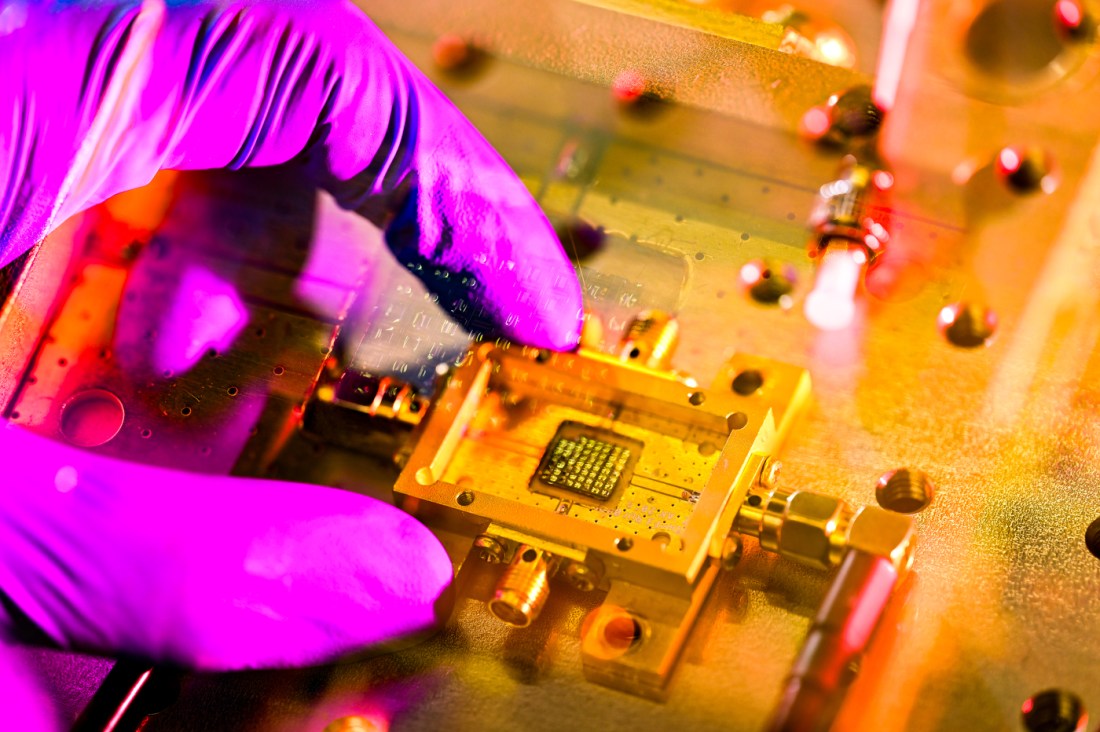

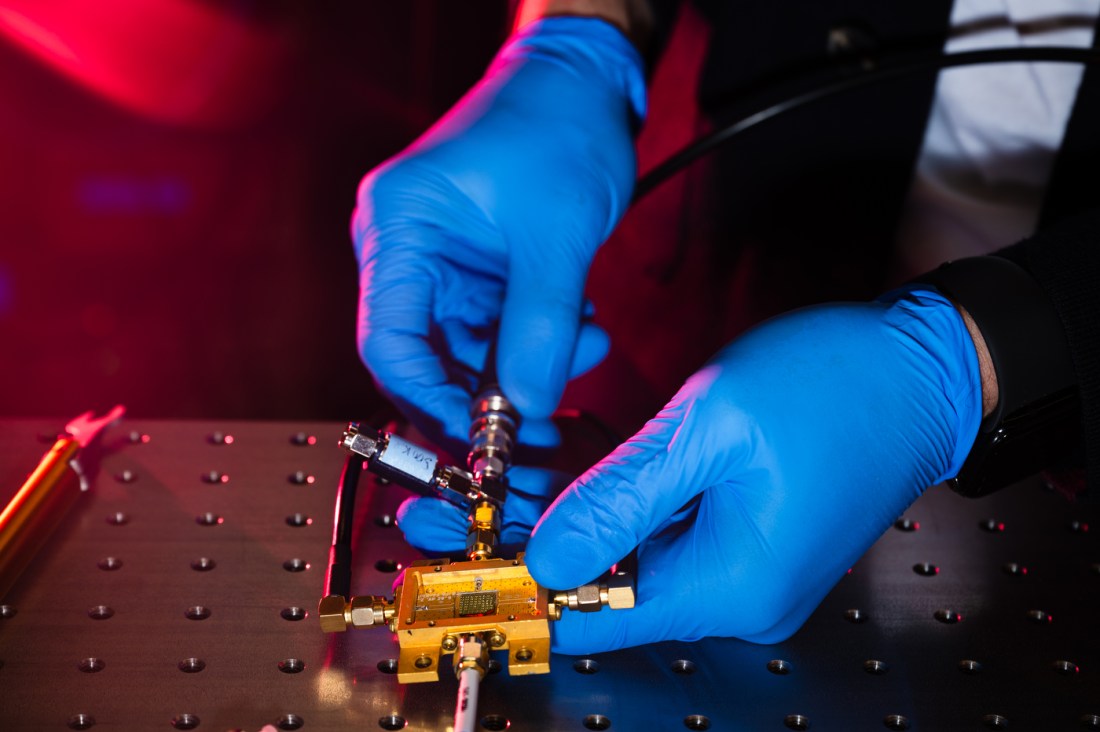

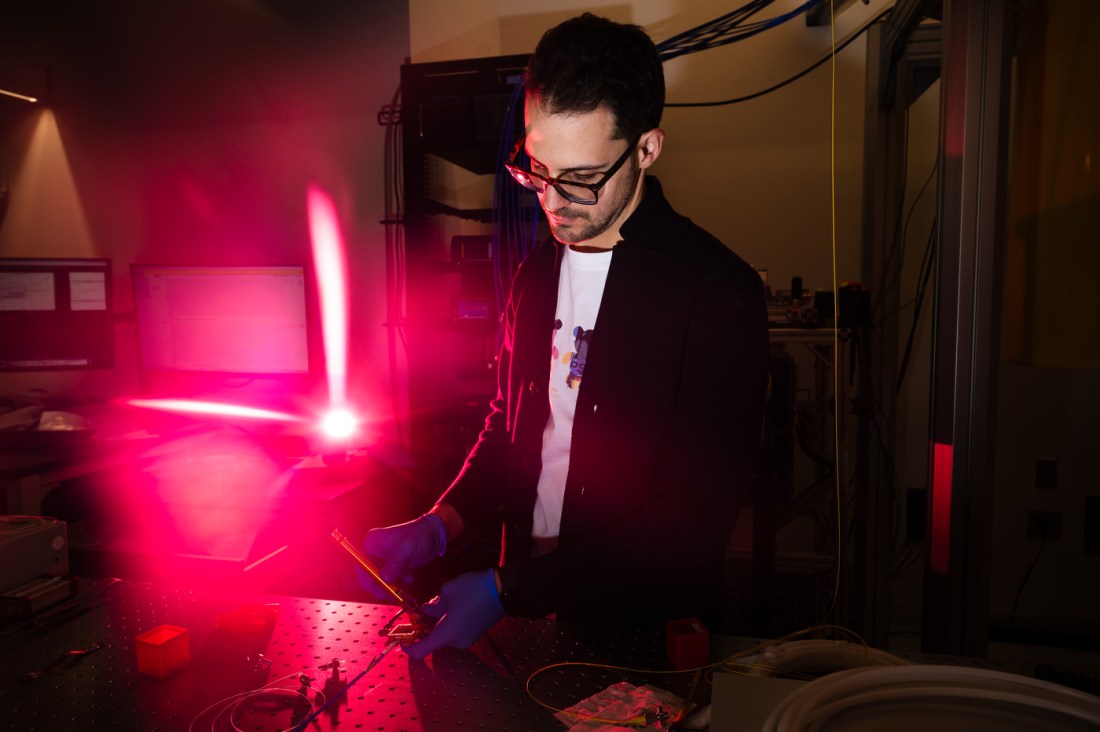

12/11/25 – BOSTON, MA – Marco Colangelo, electrical and computer engineering and physics professor, works on a tiny, acoustic sensor at his EXP lab on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

12/11/25 – BOSTON, MA – Marco Colangelo, electrical and computer engineering and physics professor, works on a tiny, acoustic sensor at his EXP lab on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

12/11/25 – BOSTON, MA – Marco Colangelo, electrical and computer engineering and physics professor, works on a tiny, acoustic sensor at his EXP lab on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

12/11/25 – BOSTON, MA – Marco Colangelo, electrical and computer engineering and physics professor, works on a tiny, acoustic sensor at his EXP lab on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

12/11/25 – BOSTON, MA – Marco Colangelo, electrical and computer engineering and physics professor, works on a tiny, acoustic sensor at his EXP lab on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

12/11/25 – BOSTON, MA – Marco Colangelo, electrical and computer engineering and physics professor, works on a tiny, acoustic sensor at his EXP lab on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

12/11/25 – BOSTON, MA – Marco Colangelo, electrical and computer engineering and physics professor, works on a tiny, acoustic sensor at his EXP lab on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

12/11/25 – BOSTON, MA – Marco Colangelo, electrical and computer engineering and physics professor, works on a tiny, acoustic sensor at his EXP lab on Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Marco Colangelo, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, works on the topological guided acoustic wave sensor invented by him, Cristian Cassella and Siddhartha Ghosh. Photos by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Colangelo is an expert in condensed matter physics, which, according to the journal Nature, studies how matter behaves at the atomic scale while solid.

Their discovery hinges on something in condensed matter physics called topological interface states. These states allow the researchers to hone energy down to nano-scale regions, focusing on very narrow, highly localized areas without the degradation of performance that comes with scaling down the entire apparatus. One nanometer is one-billionth of a meter.

Because of its accuracy, Cassella says, the potential applications extend from quantum computing to precision medicine. He calls this “a seminal study that shows a completely new technology,” which could lead to progress across the sciences and engineering.

Ghosh says that their approach means they avoid the traditional limitations in trying to scale devices smaller and smaller, instead using “some clever physics” to get around those limitations.

A sensory revolution

Called a topological guided acoustic wave sensor, the researchers’ first experiment was a proof of concept, detecting a low-powered, infrared laser with a diameter of five micrometers. That’s about a tenth of the width of a human hair.

“Here we are really able to distinguish very small levels of excitations and very localized parameters,” Colangelo says. His excitement stems primarily from the new kinds of physics research these devices open up. “There are some hypotheses on how the physics works behind these devices that are not validated yet,” he continues, but a deeper understanding of that physics will also help push the practical applications.

Ghosh remains cautious about predicting the new technology’s future importance, but also thinks it’s a very exciting discovery that opens up lots of future research avenues.

When ascribing authorship to the project, both Colangelo and Cassella demur to the other. Colangelo lauds Cassella for leading the project, while Cassella is quick to point out that the project was only possible with the support of a grant Colangelo received from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

“I think, probably, we’re going to work on this technology for the next 10 years,” Cassella says.

Noah Lloyd is the assistant editor for research at Northeastern Global News and NGN Research. Email him at n.lloyd@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter at @noahghola.