1. a. Which emerging science and technology areas (e.g., artificial intelligence) will be key to the next generation of innovative advanced manufacturing technologies, and how will they impact advanced manufacturing?

A wide suite of digital manufacturing technologies—including artificial intelligence (AI) (and individual AI applications such as AR/VR, computer vision, expert systems, digital twins, and robotic process automation), big data, cloud computing, the Internet of Things, sensors, robots/cobots, advanced wireless communications, and computer-aided design (CAD) and engineering (CAE) software—tools are poised to transform modern manufacturing. In fact, digital services now account for 25 percent of manufacturing inputs.[1] And electronic inputs account for 40 percent of the value of a modern vehicle.[2]

The application of digital manufacturing technologies will be significant. Analysts expect manufacturing digitalization to boost overall global factory productivity up to 25 percent.[3] One assessment finds manufacturing digitalization could produce a 10 percent improvement in overall operating efficiency; 25 percent improvement in energy efficiency; 25 percent reduction in consumer packaging; 25 percent reduction in safety accidents; 40 percent reduction in cycle times; and 40 percent reduction in water usage.[4] Overall, economists estimate manufacturing digitalization could boost annual U.S. productivity growth by 1 to 1.5 percentage points and add $10 to $15 trillion to global GDP over the next 20 years.[5]

Manufacturers stand at differing levels of implementing smart manufacturing solutions. One March 2025 study of over 800 large multinational manufacturers found that 98 percent have at least initiated digital transformation efforts seeking to improve their customer experience and operational efficiency, optimize costs, or enhance products.[6] However, implementation of digital manufacturing solutions is decidedly lower among small- to medium-sized (SME) manufacturers. A 2024 survey conducted by the Interdisciplinary Center for Advanced Manufacturing Systems (ICAMS) at Auburn University found that 56 percent of U.S. SME manufacturers were either currently using or now implementing automation tools and 49 percent using additive manufacturing, but that only 38 percent were using big data, only 28 percent AI, and only 27 percent data analytics.[7]

The United States significantly trails in the deployment of robotics—a cross-cutting automation tool that will be vital to the competitiveness of myriad U.S. manufacturing industries. In fact, China has installed more industrial robots than the rest of the world combined in each of the past five years. When nations are assessed by their deployment of industrial robots per 10,000 workers, the United States ranks tenth, while China ranks third.[8] The United States needs to significantly scale up its deployment of industrial robots, and ITIF laid out a strategy to do so in its recent report “A Time to Act: Policies to Strengthen the US Robotics Industry.” Several recommendations which stood out from the report include that the United States should develop a national strategy for robotics, the Department of Commerce should convene a robotics industry advisory group to advise the U.S. government on robotics industry needs and how to increase adoption and procurement, and the United States should expand its investments in commercially oriented robotics research and development (R&D).[9] Further, president Trump should issue an annual award at the White House to firms that have done the best job of installing robots, and use his bully pulpit to shame other executives who have gone capital-light and failed to invest in automation.[10]

1. b. What are the primary challenges and barriers that need to be addressed to ensure the successful integration and widespread adoption of emerging technology in manufacturing?

A litany of supply and demand challenges continue to inhibit the wider adoption of emerging technologies in U.S. manufacturing. One challenge is that the technologies are still evolving and not yet fully mature. As Industry Week’s Jessica Davis notes, “Implementing an Internet of Things program isn’t exactly like flipping a switch. There’s a lot involved, from sensors where the data is initially collected to the network the data travels, to the analytics systems that figure out what it all means.”[11] A lack of interoperable standards between vendor solutions represents another significant challenge. As the report “Industrie 4.0 in a Global Context: Strategies for Cooperating with International Partners” explains, “individual modules, components, devices, production lines, robots, machines, sensors, catalogues, directories, systems, databases, and applications will need common standards for the connections among them and for the overall semantics, or how data gets seamlessly passed from one device to another.”[12] Thus, standardization of architectures, data-exchange formats, vocabularies, taxonomies, ontologies, and interfaces will be key to creating interoperability between different digital manufacturing solutions, and the U.S. National Institute of Standards (NIST) can play an important role in facilitating this.

Recent research from the Boston Consulting Group and McKinsey has found that 70 percent of digital transformation initiatives fail to meet their objectives.[13] A significant reason why pertains to lagging employee skills and competencies to effectively implement digital solutions and to a lack of clarity regarding the value proposition behind digital implementations. This is why many countries inventory and describe discrete, specific manufacturing digitalization use cases and processes. For example, Germany has documented over 300 specific use cases/sample instantiations of SME manufacturing digitalization.[14] Further, as the subsequent section on small manufacturers will document, they often lack the capital to invest in modernized plant and equipment.

A second challenge is that too many U.S. companies seek to go “asset light,” limiting investment in capital assets to make their balance sheets more favorable to investors. It is beyond the scope of this submission to address this issue, but a task force led by Treasury and including other major financial agencies, including the Securities and Exchange Commission and banking regulators, should seek solutions to this.

2. a. Which disruptive manufacturing technologies (e.g., additive, nanotechnology, biotechnology) hold the potential to eliminate reliance on foreign sources for critical minerals and materials, and how will they do that?b. What are the technical challenges and barriers associated with implementing these technologies at an industrial scale, and how can they be addressed?

The United States must make it a national imperative to decrease dependence on China for key critical minerals. For instance, for rare earths used in magnets—notably neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium—China accounted for about 60 percent of their global mining and 90 percent of their refining and processing in 2024.[15] Overall, China accounts for around 60 percent of the global supply of battery-grade lithium, 65 percent of nickel, 70 percent of cobalt, and 90 percent of rare-earth elements such as neodymium.[16] China is also the primary global supplier for many key active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). For instance, approximately 70 percent of the world’s paracetamol (acetaminophen) originates from Chinese firms and over 80 percent of key antibiotic actives (e.g., doxycycline and amoxicillin) are produced in China.[17]

The only way the United States can restore its capacities in critical mineral/rare earths processing and refining in a manner that’s cost-competitive with Chinese production while still being environmentally friendly is through innovation. This will require novel, innovative, new-to-the-world refining processes to address China’s lead in this field. This will require ample R&D funding from both the public and private sectors and also the funding of Ph.D. researchers to develop these new processes. As such, the United States should establish a new National Science Foundation (NSF) Engineering Research Center (ERC) for critical minerals refining and processing.

4. a. What are examples of U.S. manufacturing-related technological, market, or business challenges that may best be addressed by public-private partnerships and are likely to attract both participation and primary funding from industry?b. How can public-private partnerships be structured to overcome potential hurdles and foster successful collaboration?

The Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft represents Europe’s largest application-oriented research organization, comprised of 67 institutes. One of the historically great strengths of Germany’s Fraunhofer system is that it brings German industry and academia together in a structured manner to develop new technologies with specific industrial relevance.[18] Each Fraunhofer is co-led by a representative from industry and academia. The Fraunhofers work with specific German industrial sectors to develop 10-year technology roadmaps for industry, identifying specific technical hurdles or challenges that need to be addressed, and then through the associated universities they fund Ph.D.s to solve those technological problems and then diffuse that knowledge back throughout Germany’s industrial ecosystem. The German government at the federal and state levels co-invest in the effort, covering about 30 percent of program costs.

America’s Manufacturing USA network is somewhat modeled after this approach. But what it really points to is that the United States should be developing manufacturing-sector-specific competitiveness and innovation strategies. The semiconductor industry has long done this well, and even now the Semiconductor Research Corporation (SRC) has articulated a Decadal Plan for Semiconductors, which has defined specific research challenges such as energy management, storage density, security-on-chip, etc.[19] Similarly, ITIF has called for the Trump administration to encourage the creation of the biopharma equivalent of the SRC.[20] Here, industry could collaborate on such a production technology innovation roadmap, and the federal government could match their funding to research institutes and universities on a dollar-for-dollar basis. For example, some life-sciences firms have their own roadmaps (e.g., GlaxoSmithKline’s manufacturing technology roadmap is focused on the use of continuous techniques).[21]

Beyond biotechnology and semiconductors, the United States should be developing similar decadal competitiveness strategies/technology roadmaps for key manufacturing industries including aerospace, automotive, chemicals, robotics, machine tools, shipbuilding, etc. The U.S. government should be a partner with American academia and industry in helping develop these strategies, but unfortunately it lacks not just the resources but also the key data to undertake the analytics necessary. For this reason, ITIF has laid out a comprehensive assessment of what are the federal statistical needs that would underpin a comprehensive “National Advanced Industry and Technology Strategy.”[22]

Ensuring that small manufacturers can tap into the technological expertise being developed by the Manufacturing USA Institutes is important. A following section discussed improving Manufacturing USA/Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) coordination. While each of the Manufacturing USA Institutes have different business models/value propositions, some have created unique pathways for SMEs to engage with them, such as how MxD (focused on digital manufacturing) offered $500 subscriptions for a low-tier set of outputs. Each Manufacturing USA Institute should have an SME engagement strategy.

5. a. How can Federal agencies and federally funded R&D centers supporting advanced manufacturing R&D facilitate the transfer of research results, intellectual property, and technology scale-up into commercialization and manufacturing.5.b. What are the key challenges in translating research findings into commercially viable manufacturing processes and products, and how can they be overcome?

First and foremost, America needs to adopt and maintain a supportive, and non-disruptive, approach to the effective technology and intellectual property (IP) transfer system the United States has already developed, and to the extent it reforms this approach it should focus on value-adding improvements on the margins. The administration should also recognize that the process of IP/technology commercialization is already risky, difficult, expensive, and fraught with many valleys of death.

The Trump administration should further recognize that the United States has already built the world’s most effective system for technology commercialization, especially when it pertains to IP/technologies derived from federally funded R&D conducted at U.S. universities and research institutions. However, as late as 1978, the federal government had licensed less than 5 percent of the as many as 30,000 patents it owned.[23] Most of them languished on the shelves of government offices or labs. Congress transformed the situation by passing the bipartisan 1980 Patent and Trademark Law Amendments Act, better known as the “Bayh-Dole Act.” The legislation both created a uniform patent policy among the many federal agencies funding research and allowed universities to retain ownership of the IP and inventions made as a result of federally funded research.[24] The Bayh-Dole Act has transformed U.S. universities into engines of innovation, spawning robust academic technology transfer and commercialization capabilities and activities at hundreds of universities across the United States that have led to the launch of over 18,000 start-up companies.[25]

The Trump administration should focus first on preserving the effective operation of the Bayh-Dole framework. When Congress passed the Bayh-Dole Act it included so-called “march-in right” provisions, which permit the government, in specified circumstances, to require patent holders to grant a “nonexclusive, partially exclusive, or exclusive license” to a “responsible applicant or applicants.”[26]

The Bayh-Dole Act specifies only four instances in which the government is permitted to exercise march-in rights, and reasonable prices isn’t one. Yet some have called for the government to use Bayh-Dole march-in rights to control the price of resulting products, such as pharmaceutical drugs. This despite the fact that lower prices are not one of the rationales laid out in the Bayh-Dole Act. In fact, as senators Bayh and Dole have themselves noted, the Bayh-Dole Act’s march-in rights were never intended to control or ensure “reasonable prices.”[27] As the senators wrote in a 2002 Washington Post op-ed titled, “Our Law Helps Patients Get New Drugs Sooner,” the Bayh-Dole Act: “Did not intend that government set prices on resulting products. The law makes no reference to a reasonable price that should be dictated by the government. This omission was intentional.”[28]

The Trump administration should return to an initiative undertaken in its first iteration, when it had directed NIST to undertake a review of federal policies that could bolster the return of federal investments in R&D. The final 2018 report NIST produced, the “Return on Investment Initiative: Draft Green Paper,” concluded, “The use of march-in is typically regarded as a last resort, and has never been exercised since the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980.”[29] The report further noted, “NIH determined that that use of march-in to control drug prices was not within the scope and intent of the authority.”[30] The Trump administration should build upon the findings of the 2018 NIST Green Paper and affirmatively declare that price is not a legitimate basis for the exercise of Bayh-Dole march-in rights.

As ITIF has argued, the biggest difficulty for Bayh-Dole licensees to manufacture in the United States has been the evisceration of America’s manufacturing base has denuded their ability to find manufacturing options in the United States—and so the best way to deal with this challenge is by thoroughly revitalizing American manufacturing, as this RFI helps seek to accomplish. The legislation does include some useful proposals, including directing NIST to identify and maintain a database of domestic manufacturers that commercialize products and services developed from federally funded research. The bill would also require NIST to report to Congress on the commercialization of federal research by domestic manufacturers within 18 months (of the bill’s passage).[31] One improvement ITIF has called for the legislation to make (and for NIST to implement) is for the U.S. government to develop a similar database of manufacturers in key allied nations; which could make it easier for licensees to identify alternative-to-China manufacturers when options are unavailable in the United States.

As noted, a significant strength of the U.S. innovation system is that it has turned America’s universities into engines of innovation, thanks in large part to the Bayh-Dole Act. In fact, the impact of academic technology transfer from U.S. universities has been so extensive that, from 1996 to 2020, it resulted in 554,000 inventions disclosed, 141,000 U.S. patents granted, and 18,000 start-ups formed.[32] Moreover, academic technology transfer has bolstered U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) by up to $1 trillion, contributed to $1.9 trillion in gross U.S. industrial output, and supported 6.5 million jobs over that time.[33]

In September 2025, in an Axios interview, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick called for the federal government to claim half the patent earnings from university inventions derived in part from federal R&D, erroneously asserting that “the U.S. government is getting no return on the money it invests in federal research.”[34] Yet the reality is the U.S. taxpayer—and the government—benefits greatly from this R&D funding. They benefit first from the extensive innovations produced from the academic tech transfer process, which alone has produced hundreds of life-saving drugs and vaccines, including treatments for breast, ovarian, prostate, and skin cancer, not to mention other breakthroughs in everything from Honeycrisp apples and neoprene to cloud and quantum computing. Second, university IP licensing revenues help fund key innovation-enabling infrastructure at U.S. universities, such as labs, incubators, or innovation accelerators that keep the innovation flywheel churning. Third, the government benefits from the taxes produced by the trillions in industrial output and millions of jobs created as a result of university tech transfer.[35] For instance, university research parks alone generated $33 billion in federal tax revenue in 2024.[36] The administration should refrain from imposing a claim or a tax on IP licensing revenues earned by U.S. universities.

6.a. What are the main challenges in attracting, training, and retraining a skilled workforce for advanced manufacturing, and how can they be addressed?

If the United States is to achieve its ambition to significantly revitalize American manufacturing, it needs to take further steps to ensure that it possesses the manufacturing workforce to support expanded U.S. manufacturing output. That’s especially the case as analysts expect the demand for tech talent to grow to 7.1 million tech jobs by 2034 in the United States, from an estimated six million in 2023.[37] Another report by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) finds that, by the end of 2030, an estimated 3.85 million additional jobs requiring proficiency in technical fields will be created in the United States, but that, “Of those, 1.4 million jobs risk going unfilled unless we can expand the pipeline for such workers in fields such as skilled technicians, engineering, and computer science.”[38] For the semiconductor industry, the report estimates that roughly 67,000—or 58 percent of projected new jobs (and 80 percent of projected new technical jobs)—risk going unfilled at current degree completion rates.[39] The administration should lead in several efforts to enhance U.S. manufacturing workforce skilling, including:

Expand Advanced Technological Education (ATE) program funding. Skilled technicians are a key component of the traded sector workforce. One highly successful program designed to build technician skills is NSF’s Advanced Technological Education program, which supports community colleges working in partnership with industry, economic development agencies, workforce investment boards, and secondary and other higher education institutions.[40] ATE projects and centers are educating technicians in a range of fields, including nanotechnologies and microtechnologies, rapid prototyping, biomanufacturing, logistics, and alternative fuel automobiles. Notwithstanding this, ATE funding is quite small, at approximately $74 million in FY 2025.[41] The Trump administration should work with Congress to double ATE funding to at least $150 million per year.

Expand the Manufacturing Engineering Education Program (MEEP). The engineering curricula at too many American universities is overly academic as opposed to industry focused. Indeed, university engineering programs have evolved in two troubling directions over the past several decades. First, the focus on “engineering as a science” has increasingly moved university engineering education away from a focus on real problem solving toward more abstract engineering science. Second, this focus on “engineering as a science” has left university engineering departments more concerned with producing pure knowledge than working with industry to help them solve real problems.

That’s why ITIF has argued that the United States needs more “manufacturing universities,” which would revamp their engineering programs and focus much more on manufacturing engineering and in particular work that is more relevant to industry. This would include more joint industry-university research projects, more student training that incorporates manufacturing experiences through co-ops or other programs, and a Ph.D. education program focused on turning out more engineering graduates who work in industry. These universities would view Ph.D.s as akin to high-level apprenticeships (as they often are in Germany), where industry experience is required as part of the degree. Likewise, criteria for faculty tenure would consider professors’ work with and/or in industry as much as their number of scholarly publications. In addition, these universities’ business schools would integrate closely with engineering and focus on manufacturing issues, including management of production.

One model for these manufacturing universities is the Olin College of Engineering in Massachusetts, which reimagined engineering education and curriculum to prepare students “to become exemplary engineering innovators who recognize needs, design solutions, and engage in creative enterprises for the good of the world.”[42]

Congress implemented a form of these proposals when it passed the Manufacturing Engineering Education Program into law in December 2016 as part of the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), authorizing the Department of Defense to support industry-relevant, manufacturing-focused, engineering training at U.S. institutions of higher education, universities, industry, and not-for-profit institutions. With its $48 million in initial funding, MEEP made awards to 13 educational and industry partners to bring educational opportunities to Americans interested in learning manufacturing skills critical to sustaining the U.S. defense innovation base.[43] In 2023, MEEP issued additional three-year funding grants “that establish programs or enhance existing programs to better position the manufacturing workforce to produce military systems and components that assure technological superiority for DoD.”[44]

MEEP can be a powerful initiative, but it is underfunded and has become too solely focused on engineering in the national defense context. Therefore, the Administration should work with Congress to broaden the MEEP remit to refocus it more on supporting industry-relevant, applied engineering programs at leading universities. Congress should allocate $150 million annually to a revitalized MEEP program that would make grants to 20 engineering programs at leading U.S. universities to redirect them toward more hands-on, industrially relevant engineering activities.

6.b. How can Federal agencies and federally funded R&D centers develop, align, and strengthen all levels of advanced manufacturing training, certification, registered apprenticeships, and credentialing programs.

Each Manufacturing USA Institute should develop workforce training workstreams associated with their focal technology area. For instance, MxD’s “Digital Manufacturing and Design Roles Taxonomy” identified 165 distinct digital manufacturing and design roles, describing the responsibilities of each of those roles and the skills individuals needed to accrue to fulfill them.[45] Beyond identifying new roles and occupations, each of the Manufacturing USA Institutes should work with their affiliated academic partners to build and deliver educational curricula for these positions.

The National Skill Standards Act of 1994 created a National Skill Standards Board (NSSB) responsible for supporting voluntary partnerships in each economic sector that would establish industry-defined national standards leading to industry-recognized, nationally portable certifications. But this vision has yet to be fulfilled. Therefore, Congress and the Administration should work to increase credentialing for the manufacturing and the closely related logistics industry workforce members by expanding the use of standards-based, nationally portable, industry-recognized certifications specifically designed for specific manufacturing and logistics sectors.[46]

The United States significantly underinvests in workforce training programs, dedicating just 0.1 percent of GDP in active labor market programs compared with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average of 0.6 percent of GDP, meaning America’s OECD peers such as Austria and Germany invest six or more times more in their workforce training and support programs.[47] Moreover, the United States now invests less than half of what it did in such programs 30 years ago, as a share of GDP.[48]

One way the Trump administration and Congress could address this challenge would be by expanding Section 127 tax benefits for employer-provided tuition assistance. Section 127 of the federal tax code allows employers to provide employees up to $5,250 per year in tuition assistance; the employer deducts the cost of the benefit but the employee doesn’t have to report it as income.[49] Congress should increase Section 127 to at least $8,700 (per the rate of inflation since 1996) and index the amount to the annual rate of inflation going forward.[50]

7. a. In what ways can the federal government assist in the development of advanced manufacturing clusters and technology hubs nationwide, beyond funding needs?b. Is there a need for new or expanded advanced manufacturing clusters or technology hubs for the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturers, and if so, in what sectors or technologies?c. Should Federal incentives prioritize industry-specific advanced manufacturing clusters or instead focus on technology hubs centered on advanced technologies, critical components, and materials? If so, why?

In a 2019 report, “The Case for Growth Centers” ITIF examined where innovation jobs are found in the U.S. economy, defining these as jobs that in industries that have a specified level of R&D intensity and that employ a certain share of STEM workers. ITIF found that fully one-third of U.S. innovation jobs are concentrated in just 14 U.S. counties, and one-half in 40 counties.[51] This insight was part of the inspiration behind Congressional creation of the Economic Development Adminsitration’s (EDA) Regional Tech Hubs program. EDA has designated 31 Tech Hubs and in July 2024 released $504 million in Implementation awards for 12 of the 31 designated Tech Hubs.[52]

Besides Congress not appropriating enough money, the program was poorly implemented. The Biden administration allowed NSF and the Department of Commerce (along with the Department of War and the Small Business Administration) to develop their own regional hub programs with no coordination, essentially spreading limited reasou4ces far too wide and thin. Moreover, many of the EDA awards are weak and likely to never become self-sufficient hubs once federal funding ends. The Trump administration should redo the competition, but this time fund fewer centers, make NSF and EDA develop a joint program, and ensure that winners could be self-sufficient and targeted on what ITIF calls “national power” industries (as subsequently explained).

9a. What are the biggest obstacles faced by small and medium-sized manufacturing companies in adopting advanced technologies to increase efficiency and productivity?

SMEs lag in adopting new technologies that would make them more productive, especially with regard to incorporating digital technologies.[53] SME manufacturers often lack the knowhow to implement advanced technologies or are uncertain about the value proposition behind doing so. As noted previously, this is why it’s important to describe discrete, specific manufacturing digitalization use cases and processes and to provide benchmark assessment tools so SMEs can understand where they are in their digital manufacturing journey. Another significant challenge pertains to the lack of digital workforce skills to implement digital manufacturing solutions.

SMEs often lack the capital to invest in productivity-enhancing technologies. This challenge is amplified by pressure from Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to cut costs, which further limits their ability to invest in modernized capital equipment. In fact, studies estimate that the inability of small firms to invest in equipment and plant upgrades contributes to a stark 40 percent productivity gap with large manufacturers.[54] SMEs often lack the available capital to invest in modernized plant and equipment; for instance, McKinsey research found that fully one-quarter of SMEs in the mid-Atlantic region lack the capital even to meet their weekly working-capital needs.[55] The OECD finds that access to capital has generally been tighter for SMEs in the United States than in other OECD countries ever since the Great Recession.[56]

Regarding this challenge, federal capital support (such as through upfront grants or repayable loans) could help them meet upfront investment costs (with the upgraded equipment delivering significant return on investment subsequently). This was the insight behind Congress allocating $50 million to the Department of Energy’s Office of Manufacturing and Supply Chain Resilience (MSRC) to be distributed to states for smart manufacturing pilot implementation programs.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed bipartisan Congressional legislation in the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act, which, among other initiatives, launched the Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) program. Congress originally envisioned the program—which is managed by the Department of Commerce’s NIST and which operates in all 50 U.S. states as well as Puerto Rico—as delivering expertise on quality manufacturing practices to America’s SMEs, but since then the remit of the program has broadened to be about enhancing the productivity and technological performance of U.S. manufacturing. The MEP network consists of approximately 475 service locations across its 51 centers. NIST asserts that, in FY 2024, the MEP National Network helped manufacturers achieve $15 billion in new and retained sales, $5 billion in new client investments, $2.6 billion in cost savings and over 108,000 jobs created or retained.[57] Since 2000, the MEP National Network has worked with 77,409 manufacturers, leading to $60 billion in new sales and $26.2 billion in cost savings, and has helped create and retain 1,456,889 jobs, according to NIST.[58] Elsewhere, a report from Summit Consulting and the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research found that the program generated a financial return of more than 17:1 on the $175 million in federal funds it received in fiscal year 2023.[59]

Unfortunately, the MEP program has been targeted for zeroing-out since the first Trump administration and was one of the programs designated for elimination in the Project 2025 initiative.[60] Yet the MEP program plays an important role in America’s SME manufacturer support ecosystem, and while it may merit significant reforms, the program should not be wholesale terminated.

When MEP was established in 1982, it made sense to have a network of state-focused centers working with manufacturers in each state. But a state-by-state focus presents difficulties when modern manufacturing challenges are increasingly horizontal in nature—e.g., artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, manufacturing digitalization, supply chain integration, etc.—and it makes less sense for each MEP center to develop its own capabilities in these areas independently. MEP should develop a centralized “Center of Excellence” to develop education/training/implementation modules regarding these cross-cutting manufacturing challenges and distribute them through the regional MEP delivery system.

Here, it’s imperative that the MEP program works closely with the Manufacturing USA network. America’s 18 Institutes of Manufacturing Innovation—spanning manufacturing domains from bio-manufacturing, digital/automation, electronics, and energy/environment to materials—should be viewed as “the tip of the spear” for developing advanced manufacturing product and process technologies in the United States. But MEP should be the channel through which these novel manufacturing product/process technologies get diffused to America’s SME manufacturer base. As such, each Manufacturing USA Institute should have an ongoing MEP “embedded representative” attached to it, with a mandate to develop a strategy for diffusing technologies being developed out of the Institutes across the MEP network.

Another avenue of MEP reform should be recognizing that, because supply chains cross state boundaries, MEP needs many more cross-state, sector-based MEP initiatives (e.g., autos in the U.S. Midwest and South, semiconductors in the Southwest). In other words, MEP should take on more of a supply-chain and sector-based focus. One can envision other regional/sectoral MEPs focused on wood/paper products in the Northwest, semiconductors in the Southwest, medical devices in the upper Midwest, maritime/shipbuilding in the Northeast, defense manufacturing in California or Texas, etc. If MEP departs from a predominantly state-based delivery model, it should reorient its approach to a regional/industrial delivery of SME services with a greater supply chain orientation.

A significant challenge for the MEP program has been that MEP centers often undertake small projects (average project size is about $15,000), so the engagements often don’t prove truly transformative for the customer (in part because MEP engagements often aren’t at the CEO level), and tend to engage line managers or a business unit. MEP needs to focus on transformation projects with customers, something it could better accomplish if it had longer-term, more stable funding that permitted centers to hire and retain more sophisticated staff that can build longer-term expertise.

Another way to strengthen MEP would be to emphasize assignments not just with the SME, but also their OEM customers, such as by defining joint grants (matched by the larger firm) for customers and suppliers that apply together. The larger firm’s support would demonstrate that it is committed to these suppliers and believes these suppliers are viable and strategic. It would also ease a key problem that small firms face: providing them with crucial demand-side certainty would greatly reduce the danger they face in making investments in new products or processes since they don’t have the profits to place bets that might not pay off.

For instance, ITIF has long argued the United States needs to introduce mechanisms to encourage OEMs to take more ownership of manufacturing supply chain digitalization. Large U.S. manufacturers have tended to keep their suppliers at arm’s length, too often treating them on a transactional basis with cost as the principal concern. But as the McKinsey Global Institute notes, “this approach can affect the bottom line. One McKinsey study found that inefficiencies in OEM-supplier interactions add up to roughly 5 percent of development, tooling, and product costs in the auto industry.”[61] Put simply, U.S. OEMs need to take more ownership for driving digital transformation within their supply chains. To this end, ITIF has previously argued that the U.S. government should provide incentives for U.S. OEMs to help 10,000 SMEs to become smart-manufacturing enabled within 10 years.[62]

Another potential OEM-SME partnership opportunity pertains to accumulating shared data that could help AI-based systems such as digital twins operate more effectively. Manufacturing generates more data than any other sector of the economy, yet few companies are harnessing it.[63] Yet AI systems become more effective when they have more data to train on, such as if they have data about the operating performance of production equipment or machine tools that they can learn from to predict failure modes in advance (i.e., predictive maintenance). Many companies own similar or the same machines or tools, yet the data is siloed internally and others can’t learn from it. NIST could lead a voluntary initiative where companies would share anonymized data into a shared data lake that could create new data sets against which novel AI algorithms could be developed.

10. What are examples of public-private partnership models (at the international, national, state, and/or local level) that could be expanded to facilitate manufacturing technology development, technology transition to market, and workforce development?

Two programs are here worth highlighting and targeting for expansion. The Trump administration should work with Congress to expand manufacturing-focused Engineering Research Center (ERC) programs. The U.S. National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Engineering Research Center program supports a network of 17 strategic university-industry partnerships that pursue high-risk, high-payoff research across almost the entire spectrum of technology fields—including advanced manufacturing, biotechnology, clean energy and sustainability, microelectronics and information technology.[64] Since 1985, NSF has funded 83 ERCs that have led to more than 1,400 invention licenses, 920 patents, and 250 spinoff companies.[65]

Unfortunately, NSF currently only supports three ERCs explicitly focused on advanced manufacturing activities: the NSF ERC for Cell Manufacturing Technologies (CMaT), the NSF ERC for Hybrid Autonomous Manufacturing Moving from Evolution to Revolution (ERC-HAMMER), and the NSF Engineering Research Center for Transformation of American Rubber through Domestic Innovation for Supply Security (NSF TARDISS ERC).[66] In August 2024, NSF announced a five-year investment of $104 million, with a potential 10-year investment of up to $208 million, in four new ERCs, including a new one focused on biomanufacturing-empowered decarbonization.[67] This represents progress, but it’s not enough; the administration should work with Congress to ensure at least $150 million in annual funding for the NSF ERC program, supporting both existing and new manufacturing-focused ERCs. Further, the ERCs should be required to have their federal funding matched at least half by industry in cash.

NSF should have more of its budget allocated to its Technology, Innovation, and Partnership (TIP) program, which focuses on translating use-inspired research into societal impact. An essential aspect of the TIP program is that it requires every project it funds to have an industry partner. Despite minimal appropriated resources, in just two years TIP has launched regional innovation programs, funded workforce development, improved U.S. competitiveness in two key technologies, and established partnerships with federal agencies and allies like India and Japan. Yet the program’s workforce has shrunk 45 percent since the start of the year due to cuts made by the Department of Government Efficiency and a hiring freeze. The Trump administration should work with Congress to boost TIP appropriations to at least $1 billion annually.[68]

The Industry University Cooperative Research (IUCRC) program forges partnerships between universities and industry, featuring industrially relevant fundamental research, industrial support of and collaboration in research and education, and direct transfer of university-developed ideas, research results, and technology to U.S. industry to improve its competitive posture in global markets.[69] NSF currently operates nine IUCRCs focused on advanced manufacturing innovation, with the newest one, the Center for Integrated Material Science and Engineering of Pharmaceutical Products (CIMSEPP) launched in 2022.[70] As with the ERC program, the United States could get more out of the IUCRC program to support U.S. advanced manufacturing. The Trump administration should work with Congress to provide annual funding for the IUCRC program that supports at least 15 ongoing advanced-manufacturing focused IUCRCs.

Innovation vouchers can serve as effective instruments to bring small businesses closer to local universities to collaborate on proof of concept testing or technology development. For the past several years, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) have provided technical assistance to the recipients of Department of Energy (DOE) -funded voucher programs, namely American-Made Challenges (AMC), the Incubator Program, and the Small Business Vouchers Program. This effort should be fully built out into a national program across the clean energy focused federal labs to drive strong relationships between entrepreneurs and the national labs to accelerate the roll-out of new technologies in U.S. clean energy sectors such as electric vehicle (EV) batteries and solar cells.[71]And, here, given that the United States is trailing so badly in EV battery technology to China, the Trump administration should launch such a “BatteryShot Initiative” with the goal of producing a battery with a total system cost of less than $200/kWh and a range of at least 1,000 miles per charge.[72]

11. The current 2022–2026 National Strategy for Advanced Manufacturing has three top-level goals, each with objectives and priorities: (1) Develop and implement advanced manufacturing technologies; (2) Grow the advanced manufacturing workforce; and (3) Build resilience into manufacturing supply chains and ecosystems.11a. Are these goals appropriate for the next 4–5 years? Why or why not?

These are appropriate starting goals, but the foremost goal of the National Advanced Manufacturing Strategy over the upcoming five-year period should be documented improvements in the health of what ITIF calls America’s “national power” industries.

The stark reality is that the kind of reforms and adjustments proposed above will help, but we shouldn’t fool ourselves that they will stop China from dominating advanced manufacturing. To stop that America needs much more and that will cost money and political capital. Congress needs to at least triple the R&D tax credit, something from which manufacturers are the principal beneficiary. We need a new and large source of patient capital to allow manufacturers to invest in machinery. We need to block Chinese imports of advanced manufacturing goods when they are unfairly produced and traded. We need the DOW to significantly expand its efforts beyond defense firms per se to a broad array of dual use firms and industries.

In short, U.S. manufacturing strategy should concern itself not with non-strategic industries (i.e., baseball gloves and ballpoint pens) but on enabling industries, dual-use industries, and defense industries, which collectively constitute national power industries.[73] (See figure 1.)

Figure 1: Industrial power scale

At one end of the continuum are defense industries. Clearly industries such as ammunition, guided missiles, military aircraft and ships, tanks, drones, defense satellites, and others are strategic. Not having world class innovation and production capabilities in these industries means a weakened military capability. Policymakers across the aisle generally agree that these industries are strategic and that market forces alone will not produce the needed results.

At the other end of the spectrum are industries in which the United States has no real strategic interests. These include furniture, coffee and tea manufacturing, bicycles, carpet and rug mills, window and door production, plastic bottle manufacturing, wind turbine production, lawn and garden equipment, sporting goods, jewelry, caskets, toys, toiletries, running shoes, etc. If worst came to worst and our adversaries (e.g., China) gained dominance in any of these industries and decided to cut America off, America would survive—in part, because none of these are critical to the running of the U.S. economy, as many are final goods that might inconvenience consumers but wouldn’t cripple any industries, and also because, in most cases, domestic production could be started or expanded relatively easily because none of these products are all that technological complex from either a product or process concern and the barriers to entry are relatively low.

Next to defense industries dual-use industries are critical to American strength. Losing aerospace, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, semiconductors, displays, advanced software, fiber optic cable, telecom equipment, machine tools, motors, measuring devices, and other dual-use sectors would give our adversaries incredible leverage over America. Just the threat to cut these off (assuming that they have also deindustrialized our allies in these sectors) would immediately bring U.S. policymakers to the bargaining table. National power industries tend to also need global scale in order to complete. Moreover, many are intermediate goods such as semiconductors and chemicals, where a cutoff would cripple many other industries. Finally, these industries are hard to stand up once they’re lost because of the complexity of the production process, product knowledge, and the importance of the industrial commons that support them. In other words, barriers to entry are high and, if lost, would be very difficult and expensive to reconstitute.

Finally, there are enabling industries. These are industries wherein, if the United States were cut off, the immediate effects on military readiness would be small. And the U.S. economy could survive for at least a while without production. America could survive for many years without an auto sector, as we would all just drive cars longer. But because of the nature of these industries—including technology development, process innovation, skills, and supporting institutions—their loss would harm both dual-use and defense industries. That is because enabling industries contribute to the industrial commons that support dual-use defense industries. A severely weakened motor vehicle sector would weaken the tank and military vehicle ecosystem. Similarly, a weakened commercial shipbuilding sector has weakened military shipbuilding. A weakened consumer electronics sector weakens military electronics.

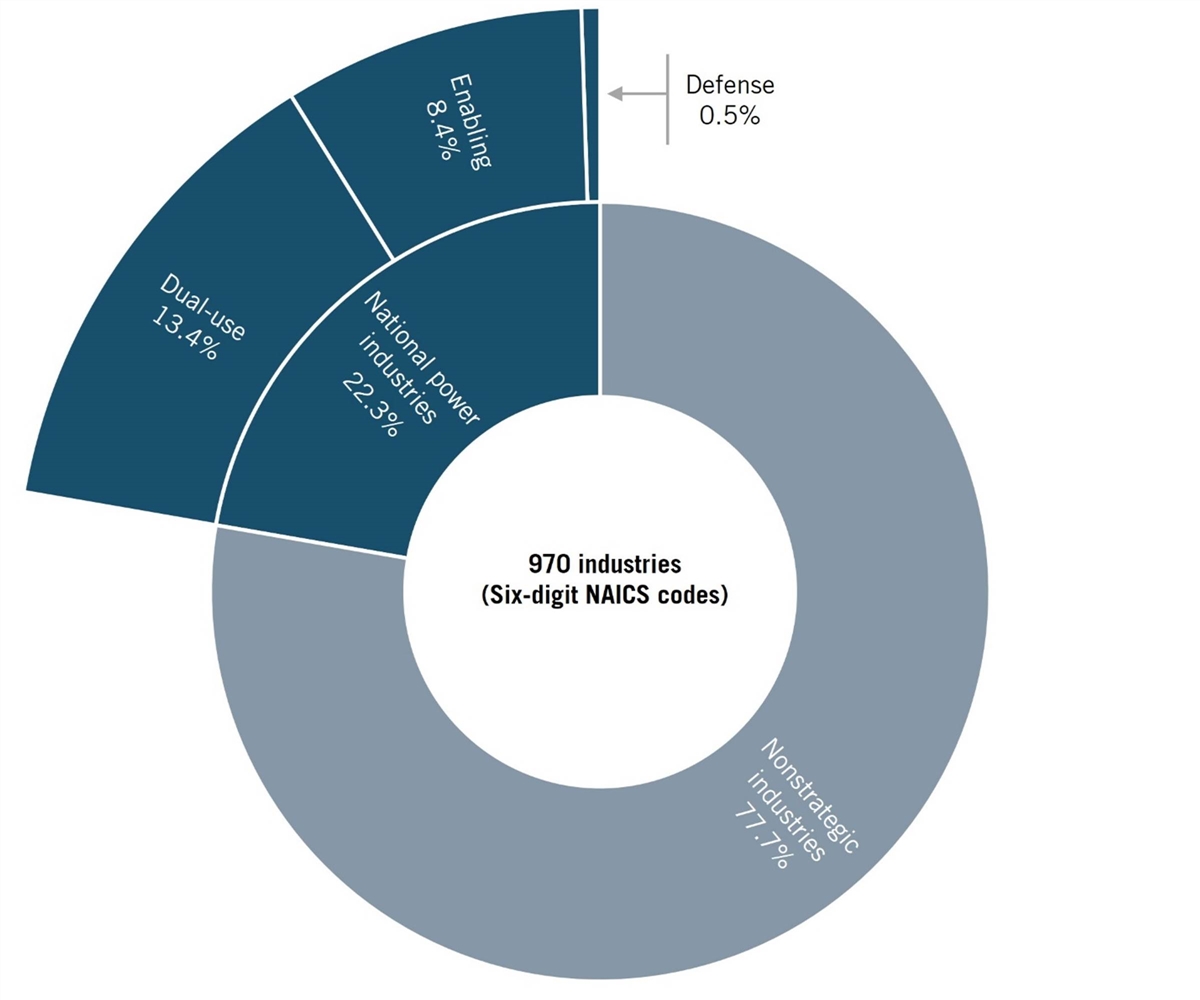

The industries that ITIF defines as national power industries represent about 22 percent of the total 970 industries delineated by the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Of these 22 percent, 13 percent are dual-use industries, 8 percent are enabling, and just 0.5 percent are defense industries. (See figure 2.) In terms of employment, just 9.5 percent of workers were employed in power industries, with 6.4 percent employed in dual-use industries, 2.9 percent in enabling industries, and the remaining 0.2 percent employed in defense industries.[74]

An analysis of several quantitative indicators of manufacturing inputs and outputs indicates that dual-use and enabling manufacturing industries have declined more than nonstrategic and defense industries over the past several years, from 2007 to 2022.

Figure 2: Breakdown of six-digit NAICS industries according to ITIF’s national power industry typology

Dual-use and enabling industries have seen the steepest declines in employment among the four classifications, with declines of 17 percent and 19 percent, respectively, compared to a 10 percent decline in nonstrategic and defense industries. Additionally, capital investment in productivity-enhancing capital, such as machinery and equipment, fell by 34 percent in enabling industries, while dual-use industries saw no change, and nonstrategic and defense industries increased investment by 7 percent and 32 percent, respectively.[75]

Nominal value added grew across all classifications, yet growth was weakest among the core manufacturing base of enabling and dual-use industries. Nonstrategic industries saw the highest growth of 26 percent, followed by defense industries (16 percent), then enabling and dual-use industries, which grew by just 11 percent and 4 percent, respectively.[76] When considering inflation, which has grown approximately 41 percent economy-wide, value added in enabling and dual-use industries declined significantly.[77]

The decline in enabling and dual-use industry output indicates a hollowing out of the U.S. industrial base, and the consequences of this are severe. These industries are most critical to U.S. national security and support domestic supply chains and national power, and they are losing ground to international competitors, namely China. China has followed a predictable playbook across industry after industry, with significant state financial backing, forced technology transfer, and IP theft, leaving American firms unable to compete and contributing to the decline of U.S. advanced manufacturing. To combat this decline and push back against Chinese economic mercantilism, the United States must implement a national power industry strategy in which the most critical industries for national power are prioritized in policymaking. As noted previously, the first step in achieving this is the crafting of industry-specific strategies.[78]

While general industrial support, such as R&D credits and full expensing for capital equipment, are valuable tools in industrial development, their impacts are limited. All national power industries differ in their structure, key players, competitive forces, and technological needs, meaning each requires curated, individualized strategic support to help firms in the United States compete in global markets. Critical industries should be highlighted and strategies developed, including a national semiconductor strategy, a national aerospace strategy, a national robotics strategy, and more. Creating these strategies will require in-depth industry research, identifying unique strengths and weaknesses, opportunities, and threats in each industry, and analyzing how federal, state, and local policy support will impact global power and competitiveness.[79]

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation commends the Trump administration for working to develop an up-to-date, coherent National Strategic Plan for Advanced Manufacturing. The success of this effort will be vital to enhancing the global competitiveness of U.S. advanced manufacturing over the coming decade.

Thank you for your consideration.

[14]. Kagermann et al., Industrie 4.0 in a Global Context: Strategies for Cooperating with International Partners.

[23]. B. Graham, “Patent Bill Seeks Shift to Bolster Innovation,” The Washington Post, April 8, 1978; Ashley J. Stevens et al., “The Role of Public-Sector Research in the Discovery of Drugs and Vaccines” The New England Journal of Medicine Vol. 364, Issue 6 (February 2011): 1, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1008268.

[42]. Ezell and Atkinson, “Fifty Ways to Leave Your Competitiveness Woes Behind: A National Traded-Sector Competitiveness Strategy.”

[46]. Ezell and Atkinson, “Fifty Ways to Leave Your Competitiveness Woes Behind: A National Traded-Sector Competitiveness Strategy.”

[55]. Phone conversation with Sree Ramaswamy, April 27, 2018.

[56]. Ramaswamy et al., “Making It In America: Revitalizing U.S. Manufacturing,” 56.

[61]. Ramaswamy et al., “Making It In America: Revitalizing U.S. Manufacturing,” 56.

[62]. Ezell et al., “Manufacturing Digitalization: Extent of Adoption and Recommendations for Increasing Penetration in Korea and the U.S.,” 44.

[69]. U.S. National Science Foundation, “Accelerating Impact Through Partnerships: Industry–University Cooperative Research Centers,” https://iucrc.nsf.gov/.

[78]. Atkinson, “Marshaling National Power Industries to Preserve America’s Strength and Thwart China’s Bid for Global Dominance.”