The Rana Choir performs on Nov. 12 for a full house at the Arab-Hebrew Theater of Jaffa.

Inbal Shani/Courtesy Rana Choir

The emotion hit its peak in a tiny theatre in the old city of Jaffa. A mixed choir – Palestinian and Israeli women, Muslim, Christian and Jewish – stood in a semi-circle, performing to a packed audience. Other than their rendition of a traditional Passover song about a goat, I understood very little. But words didn’t matter. The Rana Choir’s voices in harmony were what I needed in order to feel the thing I had been searching for since I had landed in Israel: hope.

It had been more elusive than I had expected, naively. Arriving on Nov. 8 – just under a month after the ceasefire took effect, followed by the return of all remaining living hostages – I spoke, over the course of 10 days, to as many people as I could about what’s ahead. To stay with the Passover seder theme, I focused on the declaration made at the end of the ritual dinner, after reciting the story of exile from this land: “Next year in Jerusalem.”

What will next year look like? Not just in Jerusalem, Gaza and the West Bank. But beyond this tiny country’s controversial borders. Since the war began – which, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry, has killed more than 70,000 people – Israel has become an international pariah – not just isolated, but often despised.

The war was sparked by a massacre of Israelis. Israel’s response – a catastrophic pummelling of Gaza – has ignited a reputational assault on the Jewish State. There are academic and consumer boycotts. Countries are dropping out of Eurovision, because Israel will not be excluded. A protester outside last week’s Munk Debates in Toronto on the possibility of a two-state solution wore a telling sign: “The world hates Israel.”

In Gaza, even with a ceasefire in place, fighting continues, with flare-ups that have killed more than 300 Palestinians. Meanwhile, in the West Bank, some fundamentalist Israeli settlers are attacking Palestinians – often with impunity.

While the mood in the country had no doubt lifted post-ceasefire by the time my plane touched down at Ben Gurion Airport, the optimism I hoped to find – and, honestly, craved – was in short supply, with the shaky ceasefire and a murky path to peace ahead.

Over that month, the country had gone from anguish to joy to reality.

“When the hostages came back, I went to the beach on a Saturday and with my grandchildren for a couple of hours, I was happy for the first time in two years,” Jo Even Caspi, an active member of the Israeli-Palestinian group Women Wage Peace, told me. “And after about a week of feeling kind of relieved, my thought was: okay, now we have to start working on electing the right government.”

Elections are scheduled for 2026. What happens to the Knesset in Jerusalem is top of mind. Everyone talks politics here. And nearly everyone I spoke to – I realize this is in large part self-selecting, as I sought out people who are working toward peace with Palestinians – spoke vitriolically against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Even those who might not be considered peaceniks expressed deep contempt for the current government.

Of particular concern: the lack of an independent inquiry into what happened on Oct. 7, 2023; proposed laws targeting foreign media; an anti-NGO bill that could effectively shut down peace-forward organizations operating in Israel that are critical of Mr. Netanyahu. There is concern about the increase in settler violence in the West Bank – and of course the rebuilding of Gaza and the ongoing flare-ups there. Israel’s proposed judicial overhaul – introduced in January, 2023, it would weaken the Supreme Court’s power – sparked a passionate protest movement that continues to this day.

Mickey Gitzin, with the New Israel Fund (NIF), is among those leading the charge toward a progressive, democratic and peaceful solution to “the situation,” as people call it here. When I asked for his thoughts on what’s ahead, he delivered a warning.

“I’ll say something very alarming,” he said. “I think next year will be the closest to a civil war in Israel.”

He cited violence against Palestinians, journalists and academics. It’s an internal struggle that is going to get much more intense. He’s talking Jews against Jews.

But, he added, a huge and comforting solidarity among those opposing current Israeli policies has emerged, with peace groups like his no longer considered marginal. “Since the attempted judicial overhaul, a whole camp has awakened,” he told me as we sat next to Rabin Square.

The NIF, which has a Canadian arm, funds NGOs working toward similar goals. During this war, that has included raising funds for humanitarian help in Gaza. Mr. Gitzin, like other Israeli Jews who work for Palestinian rights, has been called a traitor. (As he put it, “everyone became a traitor who is not a collaborator.”)

His group has been targeted – viciously – before. In 2010, NIF was the subject of crude ads, featuring its then-board president with a horn growing out of her head, essentially accusing the group of being self-hating Jews “for standing with and supporting the rights of Palestinians, including opposing the occupation,” as Mr. Gitzin put it.

“We realized not now, but actually 15 years ago, the concept of Israeli democracy is eroding. And it will not be one day that a military coup happens here. But a systematic change to the nature of society led by populist leaders.”

As if to illustrate his point, a few days after our interview, a colleague, NIF’s director of young leadership, was detained at the Israeli airport on his way back to the U.S., where the fund is headquartered. Airport guards had found some T-shirts in his luggage they deemed problematic, and a poster that read “Only Peace Will Bring Security.”

After questioning, he was allowed to board his plane back to the diaspora. Where so many people, like me, are keeping a close, anxious watch on what is happening in Israel, while encountering rising antisemitism at home, wherever that is.

Hostages Square in Tel Aviv on Nov. 8, 2025.

Marsha Lederman/The Globe and Mail

A huge sign looms over Tel Aviv’s Hostages Square: “Peace Upon Israel.” There’s a clock adding up the days, hours, minutes and seconds since the attacks began, 763 days earlier, on my initial visit. A burned car from outside the Nova Festival site has been moved here, a reminder of the brutality of that day. There are placards featuring photos of the hostages, yellow ribbons, and stickers memorializing the dead.

The first time I visited there were four hostages whose bodies were yet to be returned; the last time I visited, a week later, there were three. Now, there is one: Ran Gvili, 24.

Well beyond the square, those stickers remembering the dead are everywhere, along with “bring them home now” signs. Yellow ribbons are still tied to car doors and rear-view mirrors. Yellow hearts and photos of victims hang from trees. At a gelato shop, the bottom of an empty ice cream tub read: “Missing. Bring them home now.” Life goes on, but the trauma lingers.

The round fountain at Tel Aviv’s busy Dizengoff Square has become a grassroots memorial, covered in photos of Israel’s victims. Here I met with an Israeli-Canadian, Yoni Collins, who moved back from Thornhill, Ont., after Oct. 7 to document the stories of victims and witnesses in Israel. From the sea of photos, he fished out a framed collage of the eight Canadian victims of that horrible day.

“For me it’s not over,” said Mr. Collins, 30. “Until every single hostage is home, we will not officially be in October 8th.”

He was wearing a hat with a yellow ribbon symbol on it, a hostages dog tag, commemorative bracelets, a yellow ribbon pinned to his T-shirt, which featured a photo of Israeli-Canadian victim Tiferet Lapidot, and a poppy with a PTSD pin inside it. It was Nov. 11, Remembrance Day back home. Mr. Collins, who served in the IDF as a lone soldier, himself suffers from PTSD.

Yoni Collins, standing in Dizengoff Square, moved back to Israel from Canada after Oct. 7.

Marsha Lederman/The Globe and Mail

“When I came here, my mission statement, basically that I made for myself, was: for history, for healing and justice.” For history, he is filming. For healing, he is helping families and hostages. “But justice is still a big one that we’re waiting for.”

What does that look like? Among other things, he said, the country must hold a state commission of inquiry. “My friends deserve to know every detail about why they needed to bury their teenage daughters, why they needed to bury their parents, their siblings.” It’s also important, he said, for the future of Israel’s security.

Debate over the nature of this inquiry is gripping Israel right now. On my last Saturday night in Tel Aviv, I was heading to Hostages Square to observe the weekly vigil, but en route, I got sidelined by a stream of people heading in a different direction, carrying signs and flags. I followed them to a political rally calling for an independent, state commission of inquiry (rather than Mr. Netanyahu’s government-led investigation) into the Oct. 7 attacks. Whenever Mr. Netanyahu was named or shown on the video screen, the boos were so loud, I had to put my fingers over my ears.

A burned car from outside the Nova Festival site that is now displayed at Hostages Square.

Marsha Lederman/The Globe and Mail

Everyone here has a story, a history: the protesters, the justice warriors, the peace-seekers.

Ziv Stahl, 48, leads an Israeli group, Yesh Din, which monitors human rights violations by Israel toward Palestinians in the West Bank.

She is also a survivor of Oct. 7. She was visiting Kibbutz Kfar Aza, where she grew up, on that holiday weekend. There, more than 60 people, including children, were murdered and 19 others, including children, taken hostage. Ms. Stahl spent hours holed up in her sister’s safe room with her niece’s boyfriend, who had been shot, lying on the floor as they tried to help him. Her sister-in-law, Mira, was murdered.

Ten days later Ms. Stahl published a piece in Haaretz, arguing that the “indiscriminate bombing of Gaza is not the solution.”

Over coffee in Tel Aviv’s Florentin district, Ms. Stahl shared her anxiety about the NGO bill, which would make it virtually impossible for non-governmental organizations like hers, which receive funding from foreign governments, to continue operating. The bill is designed, she said, “essentially to shut us up or shut us down.”

Under the proposed law, any such NGO would face a 23 per cent tax unless it declares that it will refrain from attempting to influence public policy for three years after the donation.

At the same time, her group is dealing with the escalation of settler violence against Palestinians in the West Bank, the disturbing talk of annexation, and what she considers a critical lack of accountability for IDF actions in the West Bank.

“We need help in making Israel a true democracy and in keeping Israel safe. And I think both are strongly connected with ending the conflict and the occupation,” she told me. “Because you cannot be a democracy and hold another people so oppressed and bomb [them] and feel like you can control every aspect of their lives.”

She doesn’t harbour much optimism, but told me there is something she and her colleagues in the human rights space share: “Believing in, I don’t know, humanity, in human spirit, in the prospects and possibilities of change.

“Even if it’s documenting for the future,” she continued. “Just even to say there was some resistance. There were some people who tried. Or even to make Palestinians see that some people do try to change the situation for them and care about what’s happening to them.”

Kefaia Masarwa, 56, is a Palestinian who lives in Akka, a city known as Akko by its Jewish population, and Acre in English. After escaping a violent marriage, Ms. Masarwa joined the peace group founded by Canadian-Israeli Vivian Silver, who was killed on Oct. 7, 2023. “Women Wage Peace is like a mother to me,” Ms. Masarwa said in an interview. “They hug me and I feel free after that.” She described the group as a home for her, a family.

Ms. Masarwa is a filmmaker, a visual artist, a group counsellor and social activist. And she is a force. But after Oct. 7, she was in shock, frozen. How could she continue her work?

After a couple of weeks, she told herself: if she remained stuck, the situation would not change. So, about a month after the attacks, she organized a meeting, to which more than 100 people showed up – Arab and Jewish, women, men and children.

“Unfortunately, in the reality of this country we don’t often get an opportunity to cry together,” Ms. Masarwa states in an anthology, Women Write Hope, which is dedicated to Ms. Silver.

At a Tel Aviv café, we spoke for hours, along with Jewish WWP members Regula Alon and Ms. Even Caspi.

Women Wage Peace members, from left, Jo Even Caspi, Kefaia Masarwa and Regula Alon.

Marsha Lederman/The Globe and Mail

“We’re heading towards elections and we have to change the government,” said Ms. Alon, who liaises with women outside of Israel, including Canada, who want to support WWP. “This government, nothing will happen.”

Ms. Even Caspi said she doesn’t think real peace will happen for two generations. But the work must continue. “Hope is an action,” she said.

On hope, Ms. Masarwa told me about her son. Ansar Ayaiti, 25, is living in Toronto, seeking asylum. When I reached out to him, he told me over WhatsApp: “I am in Canada because I am looking for a safe place where I can live without fear and build a better future for myself.”

Inside the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, where some of the works on display reflect on Oct. 7 and the ensuing war.

Courtesy Tel Aviv Museum of Art/Elad Sarig

These women were on my mind when I toured through the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, next to Hostages Square, and encountered a project by the Jewish-American artist Judy Chicago: What If Women Ruled the World? Indeed.

The museums of the land are beginning to show work made specifically about the attacks and the war. At the same museum, Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi’s The Terrorist Attack at Nova Music Festival, 7.10.2023 (2024), is a bright painting of women running – or, in one case, fallen – against a blackened sky.

Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi’s The Terrorist Attack at Nova Music Festival 7.10.23, 2024.

Courtesy Tel Aviv Museum of Art/David Bachar

In the exhibition “Peace of Mind,” Palestinian-Ukrainian artist Maria Saleh Mahameed, who lives in the Arab community of Ein Mahel, presents work created during the war, including the painting Barrad (Cooler) (2025), which depicts the interior of a morgue.

Next year in Jerusalem, the Israel Museum will continue to mark its 60th anniversary – a milestone which looks very different than originally envisioned. It includes a new permanent display of Israeli art, put together “under the cloud of the seventh of October,” as the wall caption reads.

Shortly after the Israel Museum reopened following the Oct. 7 attacks, it installed survivor Ziva Jelin’s Curving Road (2010). The painting was one of the works in her studio on Kibbutz Be’eri on Oct. 7, 2023. In shades of red, it depicts the road leading into the kibbutz from the direction of Gaza. On that day, the canvas was hit by several bullets. The holes remain.

Ziva Jelin, an Israeli artist from Kibbutz Beeri in Israel’s south, stands next to her painting ‘Curving Road,’ which depicts a scene of the road leading to her kibbutz neighbouring the Gaza Strip, after it was exhibited at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem on Nov. 12, 2023.RONEN ZVULUN/Reuters

“This piece in a way was a witness,” Amitai Mendelsohn, senior curator and head of the department of Israeli art, told me. It will never be repaired, like only one other damaged piece in the museum: a Bible that was burned during the Holocaust. The damage is history.

The damage to Israel’s international standing has had a significant impact on its artists, with boycotts of filmmakers and others. The Israel Museum’s senior curator of contemporary art, Nirith Nelson, revealed there are works in the collection the museum can’t show; the artists will not give their permission. This isolation is not new. Going back many years, to a different job, she had trouble finding artists to accept a paid residency in Jerusalem. Things are much worse now. “The fact that Israel is going through a political shift … towards the right side of the political map, the artists do not want to identify with this.”

She stressed that most people in the Israeli arts scene do not agree with the current government. “We would like to show a critical picture, to show it from both perspectives. We would like to talk about it. The fact that people [outside the country] are boycotting doesn’t help the left in Israel. It actually deteriorates it. It crushes it down.”

This conversation aside, the Israelis I met rarely mentioned the growing problem of international isolation – or antisemitism in the diaspora. They have more urgent matters at hand: the hostages, a proper inquiry, peace. And many want a new government.

Still, they’ve noticed. At the Israel Museum gift shop, the attendant offered a tote bag to my friend, who lives in Paris, to go with her purchase. But he cautioned: maybe she didn’t want to carry that bag around in France; it has the word “Israel” on it.

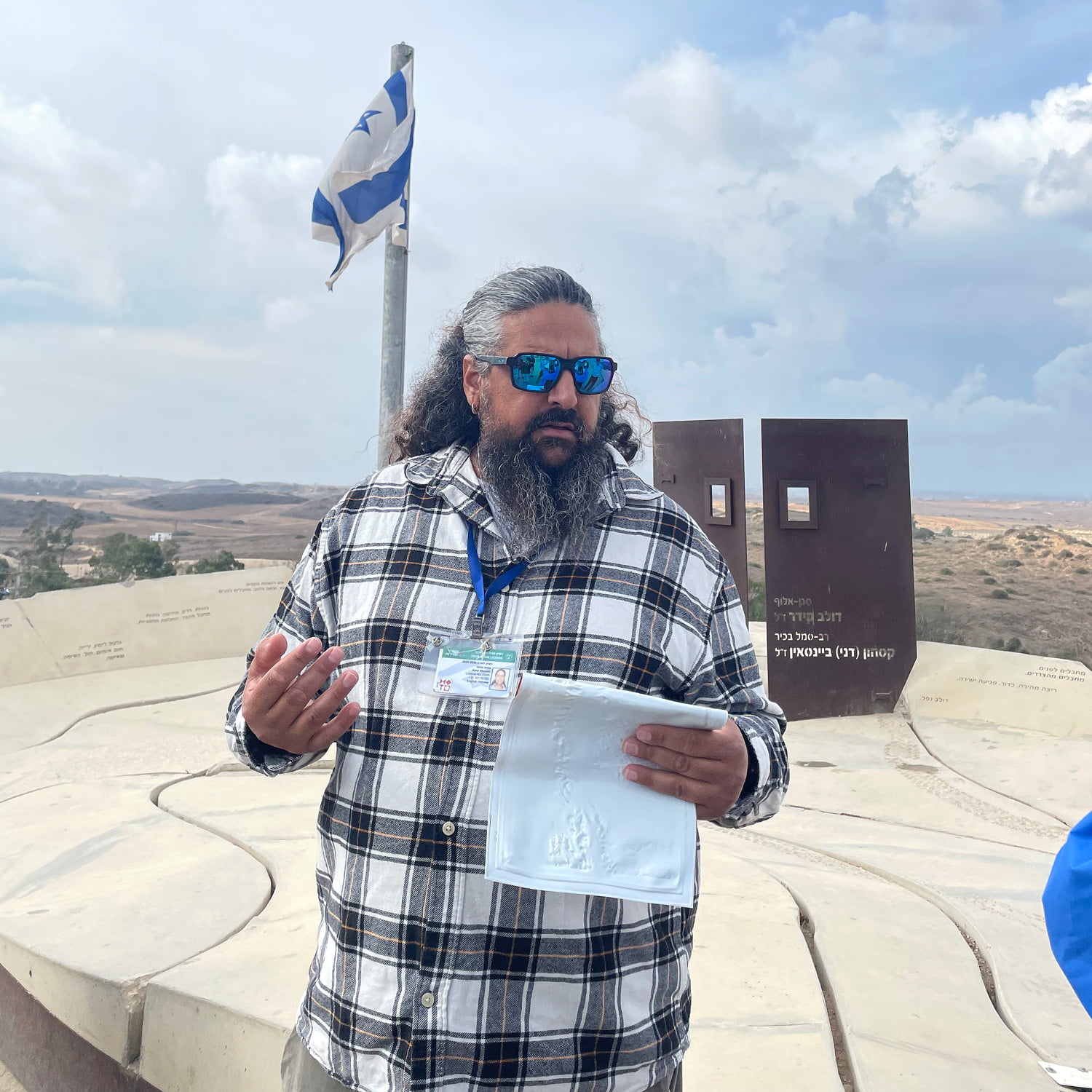

Nova survivor Amit Musaei at a lookout in Sderot. Gaza can be seen in the distance.

Marsha Lederman/The Globe and Mail

A couple of days after the Rana Choir performance, I visited the dusty site of the Nova Festival massacre on a tour led by survivor Amit Musaei.

Mr. Musaei, 42, told us his horror story, punctuated by a loud thunderstorm, as we stood, sheltered, on what had been the music festival’s mainstage. We were surrounded by memorials – so many that I couldn’t find the one I was looking for: Vancouver victim Ben Mizrachi.

As Mr. Musaei explained what happened to him and his friends, I was struck by how random life and death can be: a police officer waving the group to go right rather than left, the bomb shelter Mr. Musaei didn’t notice in his haze (and which, if he had, would have provided immediate shelter – but ultimately death). The panic when his car wouldn’t start, when he couldn’t reach his three other friends who were en route to join them but had texted first: should they stop for snacks?

The three took refuge in a bomb shelter. They were later found dead.

Mr. Musaei has been going to therapy, which allows him to return and explain what happened to visitors like me.

On the day I joined his tour, he started with a dark joke. When someone on our small bus asked whether we should buckle up, he said no. “Seatbelts will just make it one second slower when the terrorists come.” By the end of the day, nobody would have laughed at this.

We went to the city of Sderot, where images of pickup trucks roaming the streets, shooting at the police station, were among the first to go viral on Oct. 7, 2023. You can still see bullet holes on nearby buildings. The police station is gone, replaced by a memorial.

Gaza is so close, we were told, that if a siren sounds, you have 12 seconds to get to shelter. The bomb shelters on school property and at playgrounds were painted with bright flowers and cute animals – a bunny, a tiger, a cat. So the kids won’t be afraid to go inside.

From a lookout, we could see into Gaza. The destruction was not visible with the naked eye. I felt it, though. At one point, we heard gunfire. “The sound is Israel shooting in Gaza,” Mr. Musaei told us.

We were commemorating the destruction of Oct. 7, 2023. But destruction was still happening, post-ceasefire, a few hundred metres away. This was not history, this was not theoretical. People may be back in their fancy houses in Sderot – traumatized, yes, for sure – but the situation on the other side of that fence is ongoing, horrific and its outcome still unclear.

Rana Choir’s musical director and conductor Mika Danny founded the choir in 2008.

Marsha Lederman/The Globe and Mail

A few days after the Rana Choir performance, I met with its founder, conductor and musical director, Mika Danny.

It turns out the song I’d recognized, from Passover, is the choir’s signature tune, and a twist on the original. Adapted by an Italian musician and retranslated into Hebrew – and Arabic – the song includes a new verse. It laments that every year we ask the Four Questions (a highlight of the Passover seder) but this year there is one question more: “How much longer will this circle of horror endure?” The singer is someone new this year. “I used to be a lamb, a peaceful goat. Today I am a tiger and a fierce coyote.”

In Jaffa, where Ms. Danny lives, she explained how the choir came to be. In 2008, after years of going to demonstrations and signing petitions to no end, she thought something musical might be more useful. “To learn, to listen to one another – that’s the basic thing you have to do when you sing in a choir,” she told me.

Over the years, with each eruption of violence, the members talked through their feelings, before returning to singing.

But then Oct. 7 happened.

The choir was not able to tackle the happy wedding song it was scheduled to rehearse two days later. They could not even meet. Eventually, they brought in two mediators so they could have a frank, often gutting, discussion.

“In the end, the question was, do you want to continue?” Ms. Danny recalled. “The answer was yes. From everybody.”

Some of the women said they didn’t feel capable of singing – not even at home, while cooking or doing chores. So they started with breathing and movement exercises, and eventually moved to the songs.

The performance I saw at the Arab-Hebrew Theater of Jaffa was their first full concert together in Israel since the attacks and the war.

“Everybody was so happy to do it,” Ms. Danny told me. “It’s like moments of sanity; like you forget about everything for an hour, an hour and a half, and you’re in a different world.”

Even for a Canadian who couldn’t understand more than the odd Hebrew word, it was electric.

When I messaged the woman in Toronto who had let me know about the choir to tell her how profound I found the performance, Bonnie Goldberg shared some notes she wrote after her own experience.

“If the Rana Choir of Muslim, Jewish and Christian women, can find their common voice,” she wrote, “why can’t my former friends who shunned me find their way back to be my friend?”

This shunning in the diaspora has gone from shocking to almost familiar: friendships torn apart, mezuzahs ripped from doorways. For Israel, the shunning is existential, with people around the world using their platforms to question its legitimacy. Does Israel even deserve to exist?

It was, I have to say, a relief over those 10 days to not be confronted with antisemitism and a prevailing anti-Israel sentiment. There are political arguments and debates here – very heated – but at least you can skip past the should-Israel-even-exist question.

It was also a relief to meet with so many Israelis who are fighting for justice for Palestinians, while also acknowledging the trauma of Oct. 7.

It was never lost on me – visiting art museums, strolling on the beach that I had more rights as a visitor than many of the people who live here, Palestinians, have under Israeli control. I was not able to visit Gaza, obviously. Nor was I able to get to the West Bank. But I didn’t need to go there to know, with certainly, that in those places, there is a lot less of that thing I had been searching for.

The view of northern Gaza from the Sderot outlook in Israel on Nov. 14. | On the same day, a Palestinian woman walks past buildings destroyed by Israeli strikes in Gaza City.

Marsha Lederman/The Globe and Mail | Jehad Alshrafi/AP Photo