In the world’s richest country, a rural village nicknamed the new Brazil carries a saga from 1828: immigrants barred by Dom Pedro I, suspicions of thieves, family shame, and a memory rescued through theater, archives, and Luxembourgish descendants who today try to transform the old mark of failure into a local symbol.

In 1828, peasants from a poor region of Luxembourg sold everything they owned to embark for Brazil, then an Empire under Dom Pedro I, and ended up being detained before even crossing the Atlantic at the port of Bremen, Germany, returning as destitute to a land where they no longer possessed a home or land. With no option to return and viewed with suspicion, they were pushed into an isolated part of the interior, christened the new Brazil, which for generations would be synonymous with failure and suspicion.

Nearly 170 years later, in 1997, a Luxembourgish theater director staged the lives of people living in tents in rural areas, putting the new Brazil back on stage and forcing the country with the highest per capita wealth on the planet to look at its own social periphery. Since the 80s, when relatives still repeated the warning that buying a house there was “to move to the new BrazilThe story remained suppressed in many families until schools, churches, and the national archives began to retell it as part of the official memory.

The richest country in the world and its forgotten village.

Luxembourg appears in the statistics as a small European Union country with the highest personal wealth on the planet, but The contrast between the financial center and the village labeled “new Brazil” exposes a historical internal inequality..

See also other features

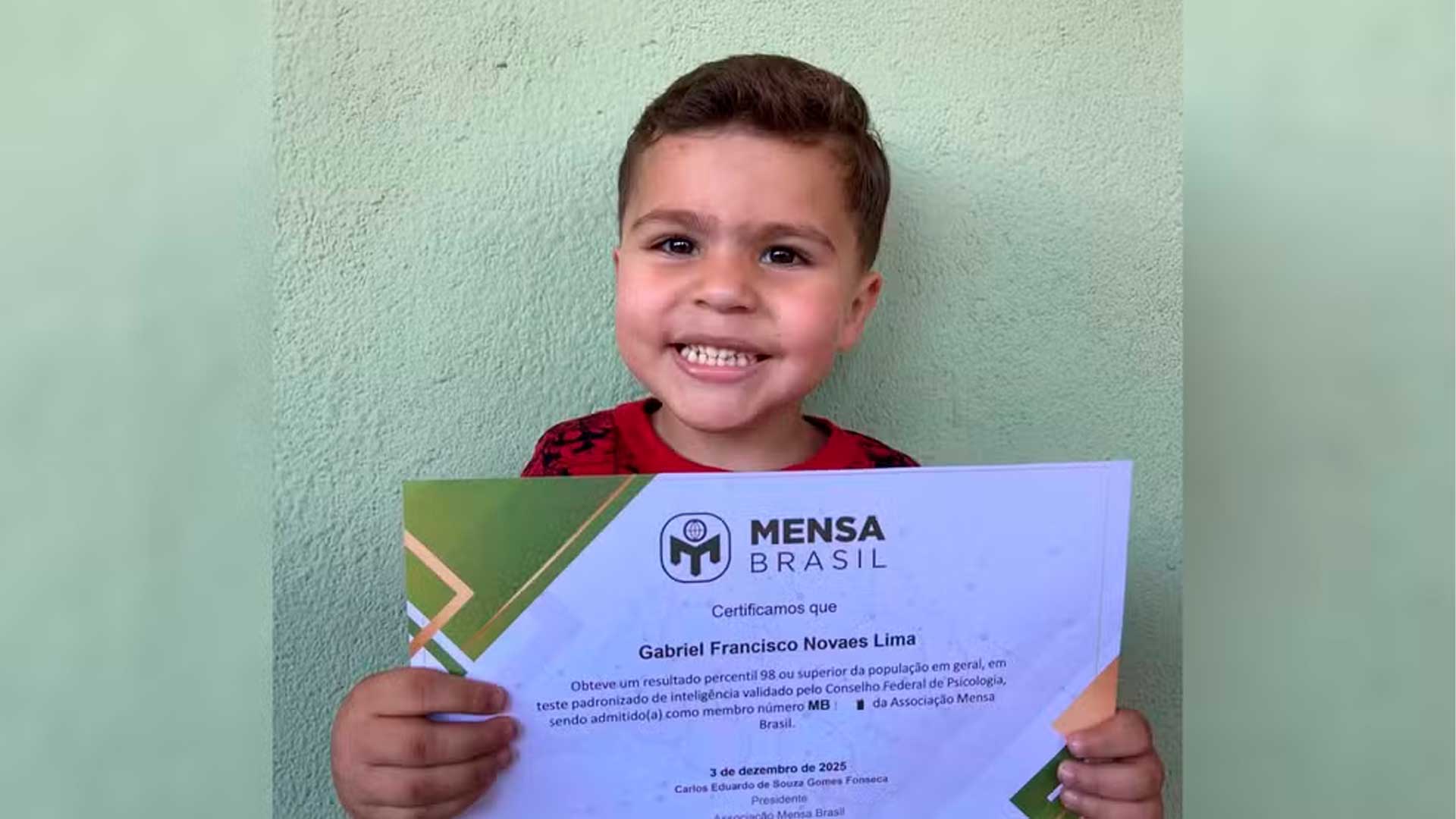

At just 3 years old and with an IQ of 132, a boy from the interior of São Paulo speaks 7 languages, is accepted into Mensa, impresses Brazil, and puts pressure on the education system to address giftedness.

Tired of the chaos in Florianópolis? Discover 3 neighboring cities with lower rent, safety, nature, planned neighborhoods, and a small-town feel, without sacrificing jobs, education, services, and stable urban opportunities.

Billionaire buys 160 hectares of the Amazon to prevent deforestation of the ‘lungs of the world’, but ends up fined R$ 450 million for illegal logging.

Few people know this about common-law marriage: notary offices are now doing something that previously only a judge could, changing the traditional dynamic.

In the rural area depicted, daily life in the 19th century was marked by hunger, high taxes, and a lack of prospects.

The inhabitants who would later be linked to the new Brazil lived in tents in the forest, in precarious conditions, at a time when allowing in, receiving, or sending back peasants without resources was a politically and socially sensitive decision.

The idea that Luxembourg is synonymous only with banks and recent prosperity erases this past of extreme poverty in parts of the territory.

Brazil’s promise in 1828 that never left the port.

At the beginning of the 19th century, rural families sold their livestock, grain, and what little property they had to escape hunger and taxes, choosing Brazil as their destination in 1828, the first year of Luxembourgish emigration to the South American country.

The plan was to cross the Atlantic from the port of Bremen, Germany, in search of that promised new life.

Before boarding, however, news arrived that would change everything. Brazil, then an Empire ruled by Dom Pedro I, It had already received too many immigrants in that year of 1828., according to the information transmitted to the groups.

From one moment to the next, the sea route closed, and the peasants discovered they no longer had a destination or anywhere to return to, because their houses and lands had already been sold.

How did the label of “thieves” originate in the new Brazil?

With no alternative, these families were settled on a specific piece of land in the Luxembourg countryside, which would come to be called the new Brazil.

From the beginning, the neighbors feared that those disinherited peasants were thieves, and the suspicion turned into a nickname and a stigma.

The label of thieves stuck to their descendants, affecting generations.

In many homes, the past linked to the new Brazil has become taboo. Older residents avoided talking about the subject, and relatives warned that acquiring a property in the region meant “going to live in the new Brazil,” an expression laden with prejudice.

The association between migration failure and territory consolidated a silent discrimination that lasted for decades.

Memory in the landscape, in the church, and in the school.

Despite attempts to forget, the memory of the new Brazil remains scattered throughout the village. The same lands that once served as pasture for animals and grain crops are a physical reminder of an irreversible decision made in 1828.

É A story that is not easily erased because it is inscribed in the landscape and in the families who remained there.

In the local church, 13 hanging illustrations summarize the misfortune of the early “Brazilians” and the founding of the new Brazil.

The images depict the return of people who had left for Brazil and came back as beggars, socially rejected, with no one wanting to have any relationship with them.

In a school in the region, some students are direct descendants of these rejected children and grow up surrounded by references to the dream of a Brazil that was never achieved, now reinterpreted with more pride than shame.

Theater and archives bring the new Brazil back into the debate.

In 1997, a Luxembourgish theatre director staged a play about tent dwellers in the countryside, recreating the atmosphere of the 19th century and giving voice to characters inspired by the history of the new Brazil.

The creator himself, in his later years, even reprised a role he had played as a young man on television, introducing the village and its name to a wider audience.

Art acted as a trigger for part of the population to begin revisiting a topic that many had repressed.

Meanwhile, the National Archives of Luxembourg holds biographies and documents of workers connected to the new Brazil, including records of those who actually managed to cross the ocean.

The documents show that not everyone was barred in 1828, and that the flow between Luxembourg and Brazil was more complex than the simplistic recollection of a single collective failure.

This documentation has been used by researchers and descendants interested in reconstructing the families’ history.

From stigma to the attempt to transform the symbol.

Today, some residents see the place marked by the new name Brazil as a symbolic space for reconciliation between the two histories.

Some advocate for the installation of a simple bench with the flags of Luxembourg and Brazil side by side, accompanied by a small plaque with the inscription “New Brazil,” to officially mark the place.

The proposal, more than just a tourist attraction, seeks to… publicly acknowledge a memory that has been hidden for a long time. Behind the jokes, suspicions, and silences.

Instead of simply recalling the failure of a crossing that never happened, the idea is to show that the new Brazil is part of the contemporary formation of the world’s richest country, revealing how it treated its poor and how… These poor people reacted.

Knowing all this, do you think the village called “New Brazil” should continue to bear the name of migratory failure, or does it need to be redefined as an acknowledged part of the history of Luxembourg and Brazil?