At an event commemorating the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, a woman in the audience asked Jonathan Granoff, president of the Global Security Institute, about the infamous false missile alert in 2018.

“Realistically,” she asked, “what can or should we do in the event of an imminent attack?”

Invoking the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War – a group of doctors which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985 – as well as the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, Granoff answered: “They all agree: you can’t do anything.”

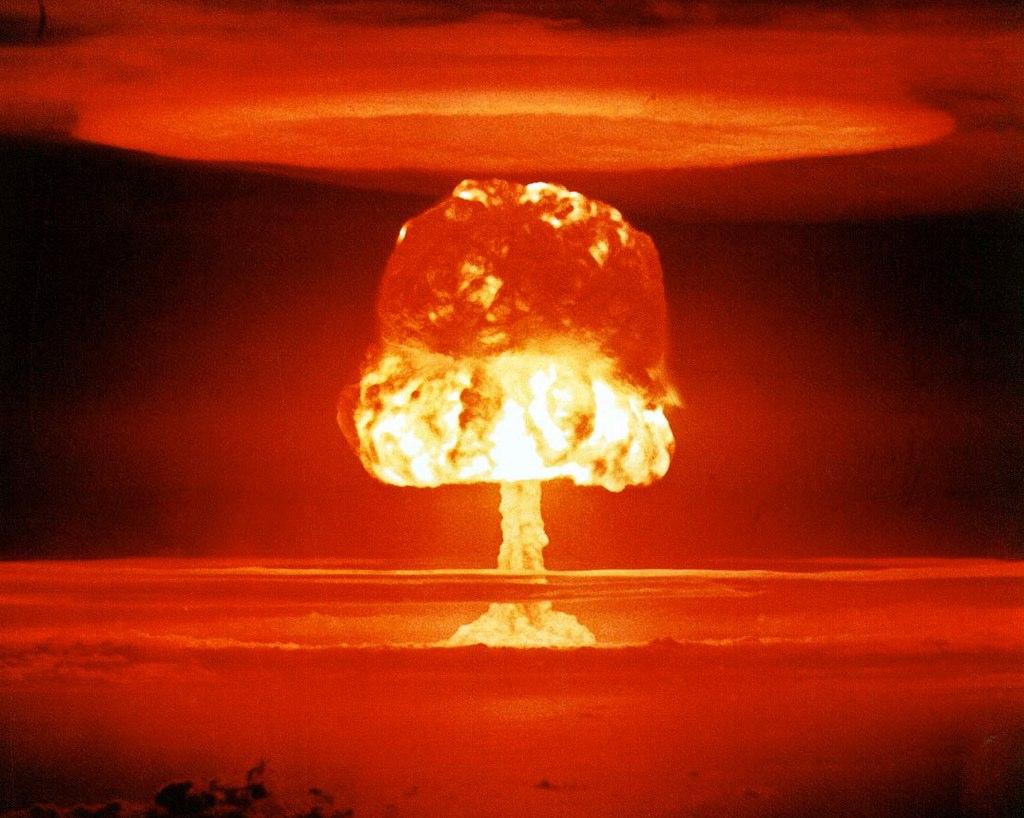

“In less than 1/1000th of a second, the heat of a nuclear bomb will be three times the heat on the face of the sun. Within 100 miles there will be winds of 600 mph, a fireball will be created that will evaporate everything in that range. The bomb used at Hiroshima was 15 kilotons, 15,000 tons of TNT. Now we have bombs in the megaton range, a million tons of TNT. We’re talking about immeasurable suffering, immeasurable destruction. There is no defense. There is no place you can hide.”

This is a difficult reality to imagine, even though we’ve collectively imagined it countless times since the United States incinerated hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians in 1945. “Terminator 2” showed mothers and their children turned to dust after a nuclear attack on Los Angeles; “Oppenheimer” dramatized the personal and political tragedies of the Cold War nuclear arms race.

Last year, Annie Jacobsen published “Nuclear War: A Scenario,” a bestselling book that detailed what could happen if North Korea launched a nuclear attack against America. Jacobsen hypothesized that such an attack would lead to global nuclear war in a matter of hours, eventually resulting in the deaths of over half of the world population. This scenario was informed by a formerly classified meeting in 1960, where the U.S. Strategic Command (then called the Strategic Air Command) finalized plans that would have killed an estimated 600 million people.

These nightmare apocalypse depictions are not without their merit. The 1983 film “The Day After” had a profound impact on Ronald Reagan, apparently changing his mind about the possibility that a nuclear war could be won. Reagan would go on to sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty alongside Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987, which led to mutual disarmament efforts.

And yet these kinds of depictions of nuclear cataclysm, while broadly accurate in their attempt to convey what is otherwise incomprehensible destruction, are clearly not sufficient. China and India are the only nations who have officially adopted no first use and minimum deterrence policies – respectively, the commitment to only use nuclear weapons in response to a nuclear attack, and only maintaining the minimum amount of nuclear weapons necessary to deter an enemy from attacking.

Hawai’i has a particularly vested interest in nuclear testing policy, beyond merely being a part of the planet that is perpetually on the edge of a self-imposed mass extinction event.

The overwhelming consensus in Washington is still one of deterrence via mutually assured destruction, which is hardly a comfort in the face of total annihilation.

In Donald Trump’s first term, the United States officially withdrew from the INF Treaty that Reagan signed; in August of this year Russia announced it will no longer abide by it, either. In February of this year, Trump said:

“There’s no reason for us to be building brand new nuclear weapons, we already have so many. You could destroy the world 50 times over, 100 times over. And here we are building new nuclear weapons, and they’re building nuclear weapons. We’re all spending a lot of money that we could be spending on other things that are actually, hopefully much more productive. One of the first meetings I want to have is with President Xi of China, President Putin of Russia. And I want to say, ‘Let’s cut our military budget in half.’ And we can do that. And I think we’ll be able to.”

This is incredibly reasonable, and laudably so for a president as prone to reckless bombast as Trump. The U.S. is projected to spend close to a trillion dollars on nuclear weapons between 2023 and 2032, more than all other nuclear states combined. If inconceivable levels of death and destruction are not enough to get us to denuclearize, surely saving billions of dollars every year is.

Alas, Trump’s sentiment has since changed. In October he announced that the U.S. will begin testing nuclear weapons “on an equal basis” with China and Russia.

President Donald Trump initially warned against the threat to the world that comes with nuclear armament. But then he changed his mind. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci/2025)

President Donald Trump initially warned against the threat to the world that comes with nuclear armament. But then he changed his mind. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci/2025)

The most charitable reading is that the announcement is itself a form of deterrence: neither China nor Russia have conducted any nuclear weapons tests in the 21st century, so perhaps Trump was warning them to keep it that way amidst rising tensions over Ukraine and increasing rivalry with China.

Even then, this leads to what is known as a security dilemma: when a country takes actions to increase its security – like developing low-yield nuclear warheads – that other countries perceive as threatening, causing them to follow suit. This ends up escalating tensions and creating an arms race, making nuclear warfare more likely.

Hawai’i has a particularly vested interest in nuclear testing policy, beyond merely being a part of the planet that is perpetually on the edge of a self-imposed mass extinction event. If the U.S. begins testing nuclear weapons again, it will likely do so in the Pacific, as it primarily did in the 20th century. More than 25,000 Marshallese citizens were exposed to nuclear fallout as a result, and followup medical studies found that 55% of cancer cases in the Marshall Islands were “attributable to radiation from fallout.”

As political scientist Van Jackson has written, the U.S. has always viewed the Pacific as a sacrifice zone, the international relations term for places that bear the burden of environmental hazards and pollution from military use — places that are sacrificed for the so-called “greater good” of U.S. military strategy. This has been true in the Marshall Islands, Guam, American Samoa, Pearl Harbor, Red Hill, Pōhakuloa … the list, of course, goes on.

All of this is bleak stuff. Nuclear weapons exist for the sole purpose to annihilate humanity at an apocalyptic scale and efficiency. That we have a trillion-dollar complex dedicated to developing these kinds of weapons is genuinely insane.

“Nuclear weapons are a human rights issue,” Jonathan Granoff told me. “What if the same mistake (of Hawaiʻi’s false missile alert) had happened between India and Pakistan? What if that happens today with Russia? Do you think we’d be exempt from that?”

There is little we as ordinary citizens can do to denuclearize our country, let alone the world. But very little does not mean nothing.

Stanford professor Scott Sagan outlined five principles to make nuclear policy “more just and effective:” prohibit the use of nuclear weapons against civilians; never use nuclear weapons against a target that can be destroyed by conventional weapons; don’t use nuclear weapons in response to enemy attacks against our own civilian populations; don’t use nuclear attacks as a response to biological or cyber attacks; work in good faith toward eventual nuclear disarmament.

We can and should push our leaders to create policies that follow the principles Sagan outlined, as well as commitments to no first use and minimum deterrence — commitments already upheld by China and India.

Luckily, here in Hawaiʻi, we have political leadership that doesn’t need to be convinced of these ideas. They only need to be pushed, relentlessly, until these goals are accomplished.

This is not a partisan issue; it’s a human one. As Trump himself said, “If there’s ever a time when we need nuclear weapons like the kind of weapons that we’re building, that’s going to be probably oblivion.”

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign Up

Sorry. That’s an invalid e-mail.

Thanks! We’ll send you a confirmation e-mail shortly.