Pedro Yusbel Gonzalez Guerra was one of more than 100 immigrants, many with their school-aged children in tow, who lined up in front of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement office in Orlando on a chilly Monday morning, waiting to find out if they will be able to spend Christmas with their families in the United States or be detained.

“It’s impossible to live in Cuba, that’s why we are here looking for refuge,” Guerra said. “I thank God this country opened its doors to us.”

Three years ago, Guerra took a harrowing journey across the Gulf of Mexico in a wooden boat alongside 30 others, including seven children. The group spent three days in rough waters, freezing and dehydrated, attempting to cross from Cuba to the Florida coast.

Since then, Pedro has been complying with every step of the immigration process, he said, while working in construction, at a restaurant and installing solar panels to make ends meet for his family. Guerra, his wife and 10-year-old son, all from Cuba, established a life in Port St. Lucie and welcomed another son last year, a U.S. citizen.

Monday, Guerra’s brother, a permanent resident, woke him up around 3:30 a.m. to drive the nearly two hours for his asylum appointment to determine if he can continue to stay in the U.S. after the Trump administration canceled temporary protected status for Cubans who had fled the Communist island.

“I pray to God that everything turns out well,” Guerra said before he entered the Orlando office.

The number of immigrants lined up at the ICE office to report for mandated check-ins has more than tripled since April, advocates say, often stretching through the parking lot and spilling onto the sidewalk. And the number of ICE detainees housed in the Orange County Jail has reached its highest level since July, averaging 75 detainees per day, according to the Immigrants are Welcome Here Coalition.

The increase is part of the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration across the nation. At the Orlando office, many families are split up once their loved one goes into the appointment, sometimes never returning.

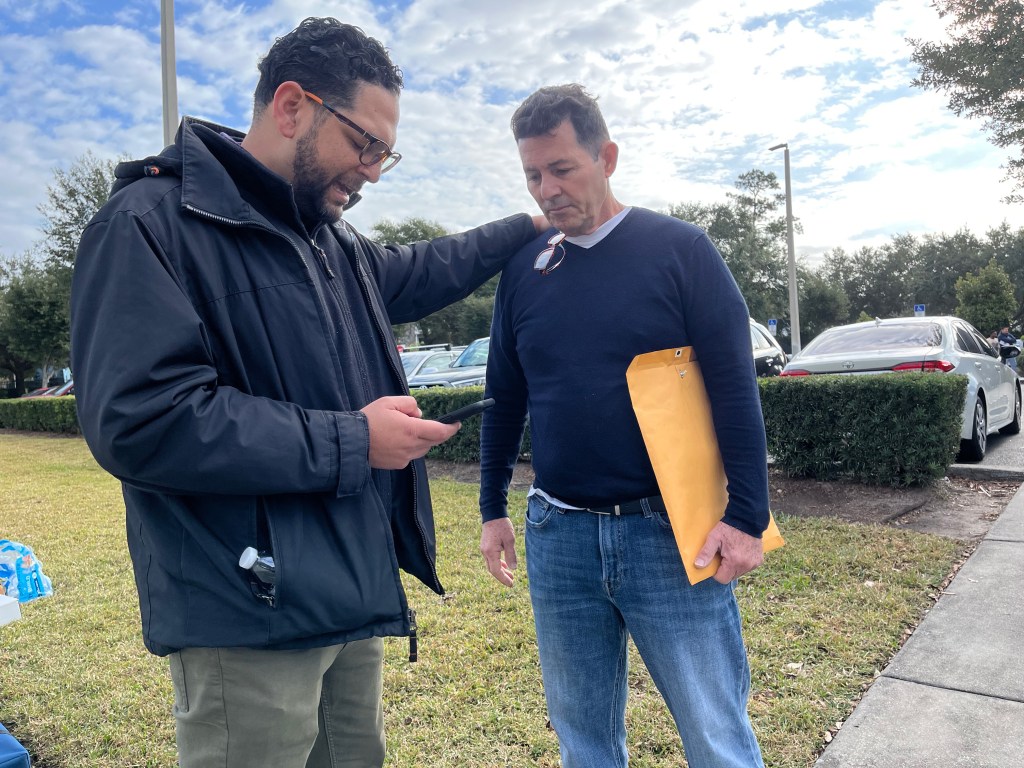

From a small tent on the sidewalk by the ICE office, two pastors, along with other volunteers, seek to help the immigrants in line. The group gathered for the final time this year, offering prayers, coloring books for kids, coffee, snacks and a printer — needed, they say, because immigration authorities sometimes demand, without prior notice, printed documents.

“We’ve been coming pretty much monthly since the summer. We started with individual folks to just accompany them in line so they don’t feel alone and decided to expand,” Pastor Socrates Perez said. “A lot of people come with fear and anxiety because they know that friends they’ve heard of or loved ones have gone in for their legal processes and they’ve been detained while they’re in there.”

Perez and Pastor Sarah Robinson, who lead the network, held a joint prayer for those in line before the office opened its doors at 8 a.m. They offered immigrants a stone with a butterfly painted on it to symbolize unity.

The immigrants in line represent the best, most law-abiding individuals, Robinson said. Many show up hours before their appointment, despite knowing they could face deportation, Robinson said. She estimated only half come out of their appointments. On Monday it was the most people in line the group has ever seen, she said.

“These are people who are doing everything in their power to do all the things that they’re being asked to do,” Robinson said. “They’re the ideal people in the ideal situation and still the stories that we end up hearing are horrible.”

For some volunteers, being there is personal. Susie Machado-Robinson, 33, immigrated to the U.S. from Venezuela with her family in 1996. She became a citizen at 13 and now works as an aerospace engineer. On Monday, she offered those in line coffee or water and helped many by answering questions in their native Spanish.

“The uncertainty is what is killer, especially if there are kids that are being ripped away from their parents,” Machado-Robinson said. “I’m so so lucky …I never had the fear of my parents being taken from me and it’s just so sad because the need is so much greater now.”

Guerra, 34, still remembered his boat trip to get to the U.S.

“Everything you ate you would throw up,” he said. “Some people even threw up blood. One of the little girls almost died, but we were able to revive her.”

Monday, he waited with many others in line and uncertain. “I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I’m terrified of going back to my country,” he said.

Nearly two hours after Guerra entered the office, and multiple people in line after him had exited, he still had not come out. By mid-afternoon, he could not be reached on his phone.

But Cuban refugee Zureli Escalona, who was one of the first in line with her four-year-old son and husband, exited the office around 9:30 a.m. She knelt on her knees and cried.

“They gave me one more year,” Escalona said through tears.