So why have millions of Iranians chosen to endure the hardship of life far from home rather than remain under the Islamic Republic?

This report draws on official United Nations figures for Iranian refugees and asylum seekers, which begin in 1980 – about a year into the Islamic Revolution.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) published no figures for Iranian refugees or asylum seekers before 1980, although UNHCR has been collecting refugee statistics since 1951.

Before the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, there were no recorded asylum cases, aside from scholarship students and legal Iranian migrants.

There are, however, personal accounts involving a small number of members of the Tudeh Party – a pro-Soviet Iranian communist party – who fled to the former Soviet Union. One such account concerns Ataollah Safavi, a former Tudeh Party member who, after fleeing to the Soviet Union, was sent to Siberian forced labor camps.

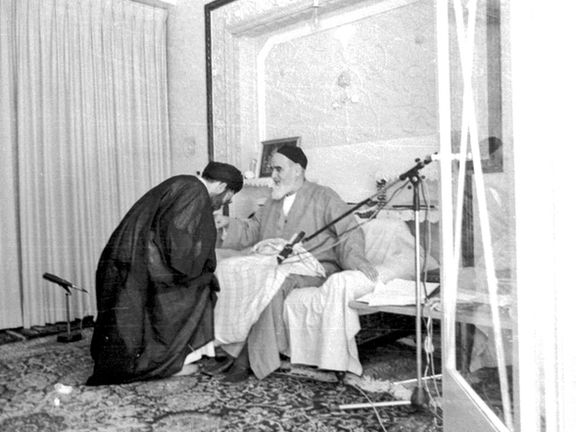

Ali Khamenei kisses the hand of Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, in an undated image.

Ali Khamenei kisses the hand of Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, in an undated image.

First decade: War years under Khomeini’s leadership

The first wave of Iranian asylum began in 1980. Shortly after the Islamic Republic was established, Iranians could still migrate relatively easily using passports issued under the previous government.

In this period, a large number of Iranians traveled legally to the United States.

From 1980, the registration of Iranian asylum seekers began with 44 cases, marking the start of a trend that would accelerate through the decade.

The first ten years, from 1980 to 1989, coincided with the eight-year Iran–Iraq war, the presidency of Ali Khamenei, and the premiership of Mirhossein Mousavi, while Ruhollah Khomeini served as Supreme Leader.

Over that decade, more than 312,000 Iranians were registered as refugees, according to United Nations data.

The peak came in 1985, when more than 88,000 refugees were recorded in a single year – the highest annual total of the decade.

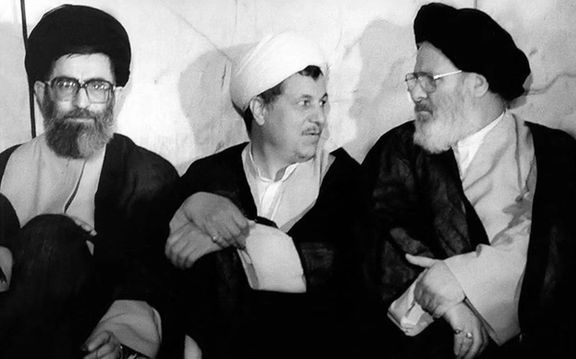

(From left) Ali Khamenei, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, and Mousavi Ardebili

(From left) Ali Khamenei, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, and Mousavi Ardebili

Second decade: Khamenei takes charge

In 1989, Ali Khamenei began his tenure as Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, and Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani took office as president – ushering in what Iran’s official political language calls the “reconstruction” era, a term used for the post–Iran-Iraq war drive to rebuild state capacity and the economy.

By the end of Rafsanjani’s presidency, inflation compared to his first year was up 478%, and the record for Iran’s annual inflation is still attributed to his government at more than 49%.

Against that economic backdrop, the trend in Iranian asylum intensified.

Over the 1990–1999 period, nearly 1.06 million Iranians were registered as refugees, with the peak in 1991, when 130,000 refugees were recorded.

After 1997 – often described in Iran as the start of the “reform era” – the pace of refugee registrations eased for a time, falling to below 100,000 a year.

Former presidents Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (left) and Mohammad Khatami

Former presidents Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (left) and Mohammad Khatami

Third decade: Reform and Ahmadinejad

In 1997, the election of Mohammad Khatami ushered in a period often described as Iran’s “reform” era, bringing a measure of optimism to parts of Iranian society.

During the first three years of Khatami’s presidency, the number of Iranians registered as refugees and asylum seekers declined modestly, before reversing course and rising again.

From 2000 to 2009, nearly 1.1 million Iranians were registered as refugees or asylum seekers, although some cases initially recorded as asylum claims may have been reclassified as refugee status in subsequent years.

A similar pattern emerged under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, whose early presidency also saw a year-on-year decline in asylum registrations. That trend, however, reversed after his first two years in office.

In 2009, as protests known as the Green Movement erupted following Iran’s disputed presidential election, refugee and asylum registrations reached their highest level of the decade.

The ministers of foreign affairs of France, Germany, the European Union, Iran, the United Kingdom and the United States as well as Chinese and Russian diplomats announcing the framework for a comprehensive agreement on the Iranian nuclear program (Lausanne, April 2, 2015)

The ministers of foreign affairs of France, Germany, the European Union, Iran, the United Kingdom and the United States as well as Chinese and Russian diplomats announcing the framework for a comprehensive agreement on the Iranian nuclear program (Lausanne, April 2, 2015)

Fourth decade: Nuclear tensions and the JCPOA

In the decade spanning 2010 to 2019, Iran’s migration pressures unfolded alongside an increasingly fraught nuclear dispute and repeated economic shocks.

Unlike earlier periods, the trend in Iranian asylum did not ease after Hassan Rouhani took office in 2013, remaining on an upward path even after the JCPOA – the 2015 nuclear accord formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action – was signed between Tehran and world powers.

After Donald Trump became US president in 2017, asylum registrations by Iranians rose sharply, reflecting the renewed strain that followed his administration’s tougher posture toward Tehran.

The same period also coincided with the rise of ISIS in Syria and Iraq, adding another layer of regional instability.

Over the decade as a whole, around 1.5 million Iranians were registered as refugees or asylum seekers.

A scene of 2019 protests in Tehran

A scene of 2019 protests in Tehran

From Bloody November 2019 to today

“Bloody Aban” is the term commonly used by Iranians to refer to the November 2019 crackdown on nationwide protests, an episode that marked a turning point in the country’s recent political and economic trajectory.

From 2020, Iran’s economic conditions deteriorated further, adding to pressures already created by sanctions and domestic mismanagement.

In the years following 2019, the overall trend in Iranian asylum and refugee registrations moved upward, with the exception of 2022, when the numbers temporarily eased.

This period was also shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic, which compounded existing strains.

In Iran, pandemic-related restrictions were imposed in 2019 and were fully lifted in 2022.

Across the six years that followed, 1,266,000 people were registered as asylum seekers or refugees.

One in every 15 Iranians lives outside Iran

United Nations data show that trends in Iranian asylum do not closely track changes of administrations in Tehran, suggesting that leaving the country has been driven more by long-term structural pressures than by shifts between governments.

There is no single, definitive figure for the total number of Iranians living abroad.

Domestic sources such as Iran’s Migration Observatory estimate the number of Iranian migrants at around two million.

Iran’s Foreign Ministry places the figure at about four million, a total that includes people born in Iran as well as a second generation born abroad.

Even so, UN data show that from 1980, when registrations of Iranian asylum seekers began, until today, 5,183,000 Iranians have been registered as asylum seekers or refugees, reflecting the scale of forced or protection-based departures over more than four decades. Of that total, nearly 4,142,000 are recorded as refugees.

Taken together with estimates that nearly two million Iranians have also left the country through legal migration, the combined figures point to a stark conclusion: roughly one in every 15 Iranians now lives outside the country.

From the outside, Iran’s migration story can appear singular. In reality, it spans legal migration and forced displacement, driven by a combination of economic pressure and political anxiety.

Many Iranians describe the same trade-off: accepting language barriers, unfamiliar cultures, and separation from family in exchange for the belief that staying offers little stability or future.