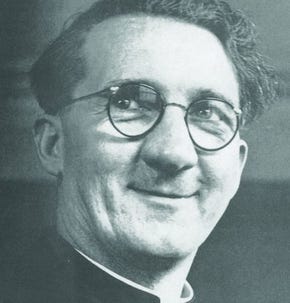

On this day, one hundred years ago, one of the bravest men Ireland ever produced was ordained into the priesthood of the Catholic Church.

Hugh O’Flaherty, born in Lisrobin, in County Cork but raised on a golf course in Killarney (his father was a steward there), attended seminary at Mungret College in Limerick. He was ordained on 20 December 1925, by Willem Cardinal van Rossum, and celebrated his first Mass the following day.

But O’Flaherty was never to become a parish priest as intended, and instead served his priesthood as a Vatican official in various roles, in the diplomatic service and the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office, which is today known as the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith but originally went by a more ominous name: the Inquisition. O’Flaherty, styled Monsignor, was known for his imposing height, stout Irish brogue, love of sport (especially, as one might expect, golf), and exemplary kindness.

For all his titles and assignments, O’Flaherty’s priesthood was defined by a role to which he was self-appointed, from which his superiors repeatedly tried to dissuade him, and which eventually caused the Pope to limit his movements for his own safety. Because this cheery golfing priest spent World War II hiding thousands of prisoners of war, Jews, and wounded partisans from the Fascist government of Benito Mussolini and later the Nazi regime that came to occupy Rome.

Drawing on his diplomatic contacts, connections within the Holy See, extravagant social circle, and more often than not sheer pluck and charm, O’Flaherty headed up a clandestine organisation of priests and nuns, Italian civilians and foreign nobility, escaped prisoners of war and officially neutral diplomats, film stars and coal men.

As Brian Fleming outlines in his excellent account, The Vatican Pimpernel, O’Flaherty is estimated to have hidden 6,500 people around Rome, the surrounding countryside, and even inside the Vatican itself, with roughly 2,000 of them civilians, including many Jews. (I can’t recommend Fleming’s book enough and have drawn on it for narrative, quotations and figures in this article. The volume is available on Amazon.)

In doing so, O’Flaherty routinely showed total disregard for his own personal safety even as he fiercely guarded that of others involved in the organisation. Despite constant surveillance by the S.S. and the Gestapo and multiple attempts to kidnap and kill him, O’Flaherty could not be dissuaded from helping anyone whose plight he learned about.

His secret ministry became so thoroughly unsecret that his name spread among prisoners of war, Jews and others, those who needed help and those eager to offer financial or logistical assistance, and every day he would stand in St. Peter’s Square praying the Divine Office and awaiting the next batch of escapees to accost him.

At its height, his organisation was spending a monthly three million lire (around £230,000 in today’s money) housing, feeding, and clothing escapees; forging passports and permits; and bribing low-level functionaries.

While lacking any formal hierarchy, the organisation’s collective leadership consisted of O’Flaherty; John May, a ridiculously well-connected servant to British ambassador D’Arcy Osborne; and Swiss diplomat Count Sarsfield Salazar; later joined by Lt. Col. Sam Derry. Key members included Delia Murphy, the singer and wife of the Irish ambassador Thomas Kiernan; movie director Renzo Lucidi and his wife Adrienne; and Henrietta Chevalier, a young Maltese widow ingenious at cramming P.O.W.s and Jews into the modest apartment she shared with her mother and daughters. The actress Gina Lollobrigida, active in the Italian resistance movement, helped out from time to time.

All were called upon to show uncommon bravery and all rose to the occasion at grave peril to their lives.

O’Flaherty’s strategic thinking and tactical cunning regularly embarrassed Obersturmbannführer Herbert Kappler, head of the Nazi security forces in occupied Rome, and Kappler made it known to the Holy See that if O’Flaherty stepped one foot outside Vatican City, he would be shot. The Pope strongly advised his priest to remain on the right side of the white line the Nazis had painted to delineate the border between the Vatican and Rome.

Yet with other members of his network under surveillance, imprisoned or killed, and with escapees appearing without warning and needing urgent transfer to a safe house, O’Flaherty often slipped out under the gaze of the S.S., disguised as everything from a road sweeper to a nun. On one occasion, he was visiting the palace of Filippo Andrea VI Doria Pamphili, a prince who helped bankroll the organisation, when Kappler learned of his presence and stormed the stately residence.

O’Flaherty evaded him by sheer luck: there was a coal delivery taking place at the time and the men put the priest in a spare soot-caked uniform, blacked up his face, and walked him out the gate right past the S.S. Little wonder he was dubbed ‘the Pimpernel of the Vatican’. (The prince was eventually sent to a concentration camp but was liberated by the British.)

O’Flaherty was particularly helpful to British soldiers, despite a fierce Irish nationalism and hostility towards Britain for its conduct in Ireland. As a seminarian, he and his friends were once seized and thrown in jail for attending the funeral of two men killed by the Brits.

Yet he repeatedly risked his life to come to the aid of British P.O.W.s, promoting one of their number, Lt. Col. Sam Derry, who was in charge of logistics and security for the organisation, to remark to the monsignor that it was ‘a good thing you’re pro-British’. O’Flaherty treated him to a bracing summation of the indignities and inhumanities that Crown forces had visited on his people that left Derry fully briefed on O’Flaherty’s loyalties.

What, then, had prompted this Irish Holy See functionary, a citizen of one neutral country residing in another, to put his life on the line day after day to resist the Nazis? In his own words:

When this war started I used to listen to broadcasts from both sides. All propaganda, of course, and both making the same terrible charges against the other. I frankly didn’t know which side to believe — until they started rounding up the Jews in Rome. They treated them like beasts, making old men and respectable women get down on their knees and scrub the roads. You know the sort of thing that happened after that; it got worse and worse, and I knew then which side I had to believe.

One photograph that particularly affected the monsignor appeared on the front page of a June 1942 edition of the newspaper Il Messaggero. It showed roughly 50 Jews being forced into labour on the banks of the Tiber. Four years earlier, Mussolini had declared the Jews an ‘unassimilable race’, banned them from studying or teaching, sacked them from the civil service, and cleared library shelves of Jewish-authored books. By the time of the Nazi occupation, Jewish homes across Rome were being raided and their inhabitants put on trains to the camps.

O’Flaherty became a staunch friend to the Jews of Rome. When Kappler demanded they hand over an impossible quantity of gold within 36 hours or face more deportations, local Jewish leaders asked O’Flaherty for help. What he did is unknown but the Pope abruptly ordered Vatican officials to hand over the requisite sum of the precious metal and Kappler was bought off, albeit temporarily.

On another occasion, a German Jew living in Rome begged O’Flaherty to hide his seven-year-old son as he and his wife were about to be arrested. The desperate father pressed into the priest’s hand a gold chain to pay for his son’s safekeeping. As ever, O’Flaherty went above and beyond, hiding the boy with some nuns and having new identities forged for his parents. After the city’s liberation, the child — and the gold chain — were returned to the family.

Following his death in 1963, and subsequent interest in his wartime activities, religious sisters from various orders have come forward with testimony about O’Flaherty’s use of their convents to hide Jews, especially children. The exact number of Jews he saved will likely never be known — records were kept on P.O.W.s but not civilians — but the figure was likely very significant. His service to am yisrael didn’t end there: he went on to help many of the Jews he had saved make aliyah to the newly founded State of Israel. It is no exaggeration to say he was the Irish Oskar Schindler.

London acknowledged O’Flaherty’s daring exploits with a C.B.E. while Washington D.C. gave him the Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm, a rare honour for a foreign civilian. The Italian state assigned him a pension but he collected not one lira of it. He was simply doing the Lord’s work. Following liberation, he lobbied the Allied occupiers for humane treatment of their new Nazi and Fascist prisoners of war. When he said, as he often did, that ‘God has no country’, he meant it.

Really meant it: when Herbert Kappler, the Nazi commander who had plotted to murder him, was convicted of war crimes and imprisoned for life, he had but one monthly visitor: Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty. In time, Kappler converted to Catholicism and it was O’Flaherty who baptised him into the faith.

O’Flaherty has been the subject of a handful of books and a 1983 T.V. movie starring Gregory Peck, The Scarlet and the Black, which I recently reviewed for Ticket Stubs. There is a statue to him in Killarney and in latter years Ireland has come to celebrate his anti-Nazi activities, even though they enraged senior Irish diplomats at the time.

But this good-humoured, staunch-hearted, boundless-spirited priest is more than a figure from history. When O’Flaherty was ordained, one hundred years ago today, Cardinal van Rossum would have prayed: ‘Censuramque morum exemplo suae conversationis insinuet’ — ‘May the example of his life lead others to moral uprightness’.

O’Flaherty is, I would submit, an example by which all of us, priest and layman, Catholic and non-Catholic, believer and atheist should commit to live our lives. In his courage, his selflessness, his generosity and his compulsion to help anyone in need, but specifically in his instinctive revulsion at the mistreatment of Jews and moral analysis that any force, no matter how powerful, that persecuted Jews had to be resisted, defied, and defeated.

We are in need of Hugh O’Flahertys in our times, when antisemitism has returned to the mainstream, when Jews are gunned down celebrating Chanukah or praying in their synagogues on Yom Kippur. When the classical antisemitism of fascists and white nationalists is in the ascendancy once more and when leftist and Islamist antisemitism continue to be respectable in universities, the media, the arts and literary circles. Even in the United States, the goldene medina, Jew-hating and Jew-baiting have escaped the fringes and become variously a content strategy, a path to electoral success, and a matter of consensus for anti-liberals left and right.

The guardrails erected after the Shoah have been dismantled and it is no longer considered indecent to heap execration on the Jews, whether in the name of the nation or of social justice. Israel is libelled as a racist state, an apartheid state, a genocidal state, a bloodthirsty murderer of gentile children, an unmatched threat to peace, an unparalleled violator of international law, and an oppressor that deserves what it gets. ‘Zionism’ is spat by those who question no other people’s right to self-determination and by those who see virtue in their own national sovereignty and shared heritage but only vice in Israel’s. They’re coming for the Jews again and they’re coming from all directions.

By his heroic example Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty teaches us that acquiescence to antisemitism is a choice and that other choices exist. And not just choices but moral imperatives: to come to the aid of Jews in need, to make their tormentor your enemy, to be for them even and especially when the world is against them, and to bear witness to the enduring evil of antisemitism.

Few of us will be called upon to demonstrate the kind of valour that Monsignor O’Flaherty did when he placed himself (and his life) between the Third Reich and the Jews it aimed to murder, but all of us are called upon by history and by conscience to lend whatever strength we can to the struggle against antisemitism and give all the solidarity at our disposal to the Jewish people.

With respect to Fr. Niemöller, it matters not when they come for the Jews or when they come for us, because they always come for the Jews and our willingness to speak against their persecution should not be contingent on the fear that the jackboot will soon be on our necks.

Antisemitism is a supreme evil and it is the duty of those who regard decency and civilisation as supreme virtues to fight it and, like Hugh O’Flaherty, live an example by which others might do the same.