The strategic outlook for 2026 offers little respite from volatility, as zones of stability contract and contested regions expand — from the Arctic to the high seas, and from cyberspace to space itself. As we approach the new year, geostrategic and geoeconomic rivalry pervades every domain and sector, shaping information systems, infrastructure and even humanitarian relief.

The long-term shift to a more anarchic world order is accelerating. This transition has been driven by successive administrations in the United States who have chosen to reduce foreign engagement, while illiberal powers have sought to reshape an order they see as unrepresentative of their interests. But the policies of the Trump administration have now given it added momentum.

This emerging global order is often described as multipolar, yet that framing is arguably premature. The U.S. still has the military and economic weight to shape outcomes more than any other state by acting or by abstaining. Its restraint or involvement — such as in Gaza, Iran and Ukraine in 2025 — show that doing less can be as decisive as doing more. American power may be declining in relative terms, but so far the material change is why, when and where it exercises it.

What is emerging instead is a multisphere world: not a stable constellation of poles, but a fluid order defined by overlapping and often competing interests, dependencies and contestation. States, China above all, are not so much dismantling as repurposing multilateral institutions to advance narrower agendas and create narratives to justify wielding power coercively. Spheres of influence are forming without fixed boundaries or shared norms to contain them.

As commitments to uphold the rules of the liberal order erode, the balance of power between states becomes the main determinant of peace and order. Institutions that once mitigated the risks of conflict are atrophying, and trust is yielding to improvisation and self-interest. While multilateral diplomacy, aid and international cooperation are in retreat, political, economic and security systems are straining beyond their limits — and global power is decisively shifting towards militarization. Global defense spending reached a record $2.7 trillion in 2024, which is about 13 times total development aid. Investing in war fighting capabilities eclipses investments in stability and development, which is a global trend that shows no sign of reversing any time soon.

Grand strategy

In a militarized balance-of-power world, assessing strategic intent matters as much as capability. What states aim to achieve and what they want others to believe rarely align. This ambiguity lies at the heart of both coercion and deterrence, particularly for China. Concealed intent and deception can confer the military advantage of surprise. Misunderstood intent can also restrain conflict or invite it. As deterrence gives way to deception and dialogue to signaling, the risk of miscalculation rises, particularly as crisis-communication channels narrow, which is increasingly the case with China and the U.S.

Assessing how either side in the U.S.-China competition will act under different conditions requires an understanding that each is pursuing quite distinct ambitions in their grand strategy. China’s is long-term, ideological and systemic: Beijing aims to build a Sinocentric order less reliant on U.S. security guarantees or the dollar, modernizing its military, reducing exposure to sanctions and tightening control over supply chains.

The U.S. under President Donald Trump, by contrast, has pivoted from upholding a liberal order to one of sovereign primacy that is inherently transactional, often performative, short-term and self-interested. This has entailed challenging the value of alliances and institutions that once amplified its influence, all while its turbulent domestic politics outwardly projects disunity and dysfunction. Disruption and unpredictability can be effective in bringing rapid results, and the Trump administration is evidently willing to exercise decisive power on the global stage, as was made clear in its brief and blunt 2025 National Security Strategy. But the extent to which such an approach may inadvertently enable China’s long-term ambitions is an open question.

At the close of this decade, it may well be said that the warning signs of crises were visible but the politics to deal with them failed: more conflict, weaker growth, dislocations in financial markets and rising civil discontent. The mechanisms and institutions built to contain risk were left to falter and the assumptions that held the liberal order together, such as respect for sovereignty and economic interdependence, gave way to improvisation, disengagement and self-interest.

Authoritarianism is also ascendant, which compounds matters of good governance and leads to greater unpredictability. According to data from V-Dem, a monitoring institute based in Sweden, there are now 91 autocracies and 88 democracies with barely one person in eight living in a liberal democracy. At the same time, the number of active armed conflicts is 61, the highest since 1946. Three-quarters of humanity now live under regimes marked by restricted freedoms or chronic insecurity. Debt, climate stress and slowing growth are eroding resilience in developing and developed states alike.

All these dynamics increase tension in a system stretched by unresolved conflicts, eroding restraint and renewed coercive power. Hybrid, or “gray-zone,” warfare conducted below the threshold of open conflict is becoming its defining feature. It blurs red lines, shifts frontlines, weaponizes trade and infrastructure and replaces deterrence by clarity with deterrence by uncertainty. Watching for the pressure points of testing, probing and provocation that could trigger escalation will be vital throughout 2026.

Conflicts in focus

Conflict risks are rising almost everywhere, and with it the potential for contagion, sudden policy changes, political crises and supply-chain disruption. In the Americas, security threats are at their highest in decades, driven by polarization and militarized policing. In Latin America, cartel rivalries and inequality sustain high levels of unrest; Colombia’s 2026 election may be the most combustible in years.

Asia remains the epicenter of global competition between the U.S. and China. China’s drive to consolidate influence and expand its military footprint will intensify, especially in the Taiwan Strait, the region’s most dangerous fault line. The risk of a limited operation under the guise of exercises, such as a blockade or island seizure, is higher than at any time in the past decade.

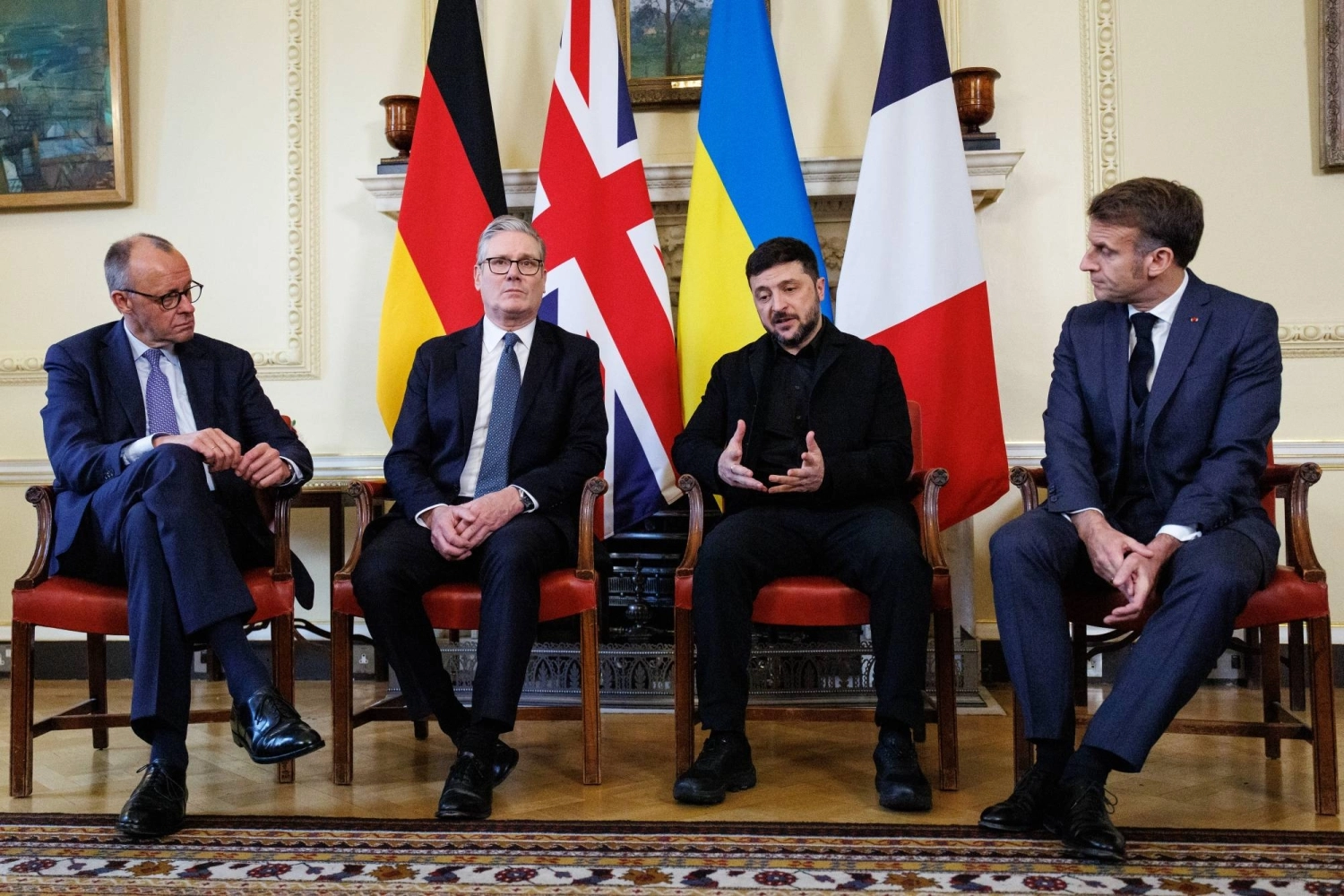

In Europe, the war in Ukraine will remain central. Moscow shows no inclination to compromise; a protracted war of attrition is the base case, deepening divisions and draining economies already burdened by inflation, debt and energy costs. Russia’s hybrid campaign aims to exhaust Western support and test defenses, betting that time will erode resolve faster than capacity.

The Middle East will remain both the crucible and a microcosm of multisphere disorder. Israel’s confrontation with Iran and its proxies will persist while Gulf states hedge with China. Lebanon’s fragility, Iraq’s factionalism and Syria’s partial recovery all leave the region vulnerable to new flare-ups. And across Sub-Saharan Africa, converging conflicts, climate pressures, coups and humanitarian crises create the world’s highest concentration of regime-instability risk.

Spheres of primacy

The second Trump administration has confirmed a worldview built on hierarchy, transaction and regional spheres. Its foreign policy is organized around spheres of influence and interests rather than shared values and rules. Alliances are recast as services to be paid for, not partnerships of mutual interest. For instance, NATO’s security guarantee risks are being framed as a billable arrangement for paying members only, with nations falling short of the 5% GDP spending target facing the uncertainty of being left to face Russia alone.

This approach recognizes only major powers as consequential actors, treating smaller states as clients whose sovereignty depends on patronal indulgence. Washington’s readiness to concede Russia a sphere in Moscow’s near abroad reflects a view of seeing the Western Hemisphere as America’s own sphere of primacy. Trump’s rhetoric about purchasing Greenland implies a mindset in which sovereignty is treated as a tradable asset. His reassertion of a Monroe Doctrine-like stance in the Americas also reflects one of transactional geopolitics — where might defines legitimacy and compromise is seen as weakness.

Europe’s response is wary. The EU and several NATO members are investing heavily in defense but remain strategically dependent on Washington. Whether Europe can turn talk of “strategic autonomy” into action will be a key test in 2026. China’s stance is more nuanced. Once excluded from great-power councils, it now seeks to dominate them. Its growing weight in global institutions like the United Nations and Word Bank reflects pragmatic multilateralism as a strategy to promote and manage the emerging multipolarity to its advantage. In 2026, tension between America’s bilateral leverage and China’s institutional capture will shape the next phase of global reordering.

Major powers are multiplying risk faster than they can manage it. Deterrence is being bought at the expense of prevention, creating a security dilemma in which every act of protection breeds new insecurity. As diplomacy thins, miscalculation becomes more likely. The U.S. remains indispensable yet unpredictable as both stabilizer and disruptor, yielding tactical gains but stimulating hedging among allies.

Viewed from abroad, each episode of political violence in the U.S. reinforces perceptions that America is distracted and divided. NATO allies question not U.S. capacity but attention span. Germany’s “Zeitenwende” — a turning point in foreign policy after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — remains incomplete, and France is constrained by domestic unrest. Japan and South Korea are planning for greater self-reliance. Multipolarity may sound manageable, but in practice it leaves smaller states exposed as debt, inflation and financial fragility rise.

Tellingly, global public debt stands at 93% of GDP; interest payments consume record shares of national budgets. A financial correction in the markets is increasingly probable. If growth slows or liquidity tightens, fiscal stress will feed political volatility. When finance and geopolitics converge, contagion can spread in both directions. The Gen Z protests of 2025 showed how swiftly economic pain can turn to political anger.

Technology amplifies exposure further. Artificial intelligence accelerates analysis but lowers the threshold for cyberattacks and disinformation. A single strike on a logistics or energy network could cascade globally within hours. The systems that deliver efficiency also transmit instability. In a world tightly bound by technology but fractured by politics, resilience will depend on how quickly actors can respond when systems fail, or when they empower the discontented.

Dynamic resilience

Not all signals point downwards. The most forward-leaning governments and corporations are adapting to turbulence rather than resisting it by building dynamic resilience: the capacity to anticipate and absorb shocks, adapt swiftly and still advance. The most agile monitor flashpoints, map exposure and stress-test plans for scenarios in which deterrence or governance fails. Resilience now lies less in strength than in anticipation and agility.

Supply-chain diversification is central to this shift. Reshoring and friend-shoring are costly but reduce dependence on single hubs. The U.S. and Europe are securing access to critical minerals through new partnerships in Africa and Latin America. These efforts merge national security with the energy transition; the two are now inseparable.

Resilience is extending into new domains. Stability in 2026 will depend less on restoring the old order than on diffusing adaptive capacity. Regional powers such as India, Japan and several European states, for example, are developing sovereign space capabilities to secure communications and intelligence. More distributed constellations and launch systems will make global infrastructure less fragile, though space itself may become the next theater of conflict.

While the overall risk picture is negative, many states see opportunity in flux. Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia and Turkey all perceive openings to raise their standing. Even the European Union, despite domestic strains, appears more cohesive than at any time in a generation. There is opportunity in a multisphere world if one accepts it as the new reality and adapts to it.

That new reality also means that geopolitical risk is now everyone’s business. Strategic advantage depends on interpreting intent and assessing capability, on understanding how power is exercised, and knowing how trade, finance and information flows are instrumentalized. Each misjudged signal or poorly informed decision carries a cost. Understanding the vectors of those risks and building dynamic resilience is where the challenge now lies.

Henry Wilkinson is chief intelligence officer at Dragonfly, a geopolitical risk consultancy, and editor-in-chief of its Strategic Outlook 2026.