Since the establishment of the Federal Reserve System in 1913, each of the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks has effectively served as a “bank” for banks. A “master account” is an account at a Reserve Bank that offers regulated depository institutions the ability to maintain account balances at the central bank. A master account holder can access Federal Reserve payments services, such as Fedwire, and settle transactions with other depository institutions through its master account.

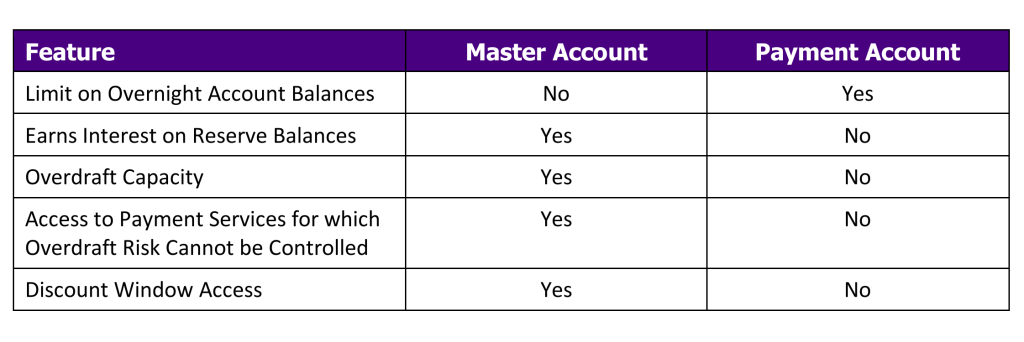

In October 2025, Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller announced that the Fed was exploring the idea of an alternative type of account, which he described as a “payment” or “skinny” account. This account, which would be more limited in nature than traditional master accounts, would be designed to benefit legally eligible institutions focused on innovations in payments.

On December 19, 2025, the Fed issued a request for information seeking public input on this concept. The Fed’s ultimate decision about whether and how to move forward with a major shift in its approach to providing accounts and services could have significant consequences for the structure, stability and resilience of the U.S. payments system.

This primer provides an overview of the risks presented by account access, the differences between traditional master accounts and the payment accounts described in the RFI, and the necessary risk mitigants the Fed should adopt if it establishes payment accounts.

Risks Presented by Account Access

Account access can present a range of significant risks. For example, the institution could pose (1) credit risk to the Reserve Bank if it overdrafts its account, (2) settlement risk to critical payments rails if it is unable to process transactions due to operational failures, (3) financial stability risk if the institution uses its account to draw deposits away from commercial banks, (4) BSA/AML risk if the institution uses its account to process transactions that support illicit activity, and (5) monetary policy risk if, for example, the accountholder could have unpredictable changes in the size of its account or the Federal Reserve is unable to use interest payments to that account to affect short-term interest rates in the economy more broadly.

Master account holders historically presented low risk along these lines. Until 1980, master account holders were Federal Reserve member banks consisting primarily of insured depository institutions, which must meet stringent requirements for capital, liquidity, risk management and consumer protection. In 1980, Congress expanded legal eligibility for master accounts to any institution that could accept deposits, including state non-member banks, savings and loan associations and credit unions.

Several years ago, however, the rise of novel charters presenting greater risks prompted the Federal Reserve to issue the Account Access Guidelines. The Guidelines establish a risk-based framework for how Reserve Banks should evaluate requests for master accounts and services. The Guidelines direct the Reserve Banks to consider the applicants’ legal eligibility and various risks that account access could pose, including but not limited to the risks described above.

The Guidelines also recognize that different types of institutions may present different levels of risk. The Guidelines therefore establish three categories of review for master account applications by eligible institutions, in which higher-tier institutions generally receive a relatively higher level of scrutiny.

Tier 1 – Federally insured depository institutions: lowest risk, less intensive review.

Tier 2 – Non-insured depository institutions subject to federal supervision at all levels by statute or commitment: moderate risk, intermediate review.

Tier 3 – Non-insured depository institutions without federal supervision: highest risk, strictest review.

A Fundamental Shift in Account Access from Insured Depository Institutions to Payments Companies

As noted above, master accounts historically have been granted to insured depository institutions and certain other types of low-risk institutions.1 This is for good reason — insured depository institutions perform a unique role in the U.S. financial system and are subject to the highest level of regulation and oversight. These institutions present lower risk because, among other features:

Comprehensive prudential oversight. Insured depository institutions are subject to robust supervision and examination at all levels for compliance with rigorous capital, liquidity, resolution and contingency planning, anti-money laundering, economic sanctions and consumer protection requirements.

Activities restrictions. Insured depository institutions—as well as their parent and affiliates—are not permitted to engage in commercial activities, which reduces risk to the bank and financial system. For this reason, the separation of banking and commerce is a longstanding principle that underlies U.S. bank regulation.

Deposit insurance. This critical part of the federal safety net supports the safety and soundness of the insured depository institution, protects its depositors, and increases trust in the financial system.

Facilitation of financial intermediation and monetary policy. Insured depository institutions engage in the “business of banking”: they take deposits, make loans and process payments. Master account access facilitates these activities while also enabling the Fed to conduct monetary policy by adjusting the interest rate on reserve balances.

Safeguards for Payments Accounts

Expanding account access beyond insured depository institutions and other low-risk institutions creates the serious risks described above, because other potential accountholders are not subject to the same standards. To mitigate some of these concerns, the RFI identifies the following important potential safeguards:

While some of these safeguards are straightforward, others — such as limits on overnight account balances — will need to be carefully designed and implemented to serve their intended purpose.

Further, institutions that are not required by law to be supervised by federal banking agencies at all levels should only be able to obtain payment accounts, rather than full-service master accounts, consistent with their risk profile. Finally, to ensure that these safeguards are applied consistently and transparently over time, they should be codified in regulations that apply to the Board and Reserve Banks.

The RFI states that the Fed is considering additional risks controls and conditions for a payment account. To that end, the Fed should consider codifying in regulation the following measures to further mitigate potential risks.

Subject all account holders to strict BSA/AML requirements. No institution with access to the

U.S. payment system should serve as a vehicle for illicit finance.

Impose a trial period. New payment account holders should undergo a testing or trial period to

monitor for potential risks.

Monitor for ongoing compliance. The Federal Reserve should conduct ongoing monitoring of

these accounts for compliance with all laws, regulations and commitments.

Do not allow pass-throughs. Affiliates or third parties that are not themselves eligible for an

account should not be able to circumvent the law by using the payment account holder for their

own benefit. In addition, as with master accounts, the RFI appropriately states that the Reserve

Banks would not recognize third-party interests in payment account balances.

No conversion to a full master account. A payment account holder seeking a full-service master

account should be required to become an insured depository institution (or become subject to

laws requiring federal supervision at all levels) to apply for a full master account.

Risk-based review process. The RFI proposes that Reserve Banks would be required to act on

payment account requests within 90 days of receiving a completed application and generally

subject these requests to a streamlined review. Given the significant risks described above, the

Reserve Banks should subject the payment account requests to an appropriately rigorous review

and should not be held to an artificial timeline.