Malta’s concrete bridges face a silent, constant battle. To the casual observer, concrete appears to be an immutable material, but it is chemically complex and vulnerable. Concrete structures have a lifeline between 50 and 100 years, however, with heavy daily traffic loads and the humid, saline air of our coastal environment, degradation can accelerate.

Concrete offers high compressive strength because it can withstand the weight of thousands of cars pressing down on it. However, it also has low tensile strength. This necessitates the use of steel reinforcement bars to hold it together. However, when salt and moisture penetrate the concrete, the reinforcement can corrode, expanding and causing cracks in the surrounding material. If these defects are not identified and addressed promptly, they can compromise the structural integrity of the entire bridge.

Traditionally, monitoring these structures has been slow, expensive, and often disruptive. Inspecting a bridge usually means closing lanes, setting up scaffolding, or bringing in heavy machinery to lift engineers to the underside of the deck. For the inspectors, it involves physical risk; for the average commuter, it means more traffic.

Our team at the University of Malta, in collaboration with Zhejiang University, is working on a novel solution to this problem. The DiHICS project (Digital Inspection of Heritage and Infrastructure Concrete Structures) is funded through the Xjenza Malta SINO-MALTA Fund 2023 Call, bringing together researchers from both institutions to explore next-generation inspection methods for concrete structures. The research is a joint effort by a multidisciplinary team including Vijay Prakash, Muhammad Ali Musarat, Wei Ding, Jiangpeng Shu, Ruben Paul Borg, Saviour Formosa, and Dylan Seychell.

From concrete to cloud

This project advocates the idea that instead of sending a human up a ladder or hanging off the side of a bridge, we send a drone. This goes beyond using the drone to take photos. It is about creating a precise 3D reconstruction of the bridge that allows for measurable analysis.

To test the methodology, the team selected two high-traffic locations: the bridge near the University of Malta in Msida and another in San Ġiljan.

The data acquisition phase required precision. Using a drone equipped with a high-resolution consumer camera, we captured thousands of high-resolution images at rapid intervals. The choice of camera was deliberate. Standard drones often have limited camera angles, typically capped at 60 degrees. By modifying the setup to achieve a 90-degree view, we could capture shadow-free shots of hard-to-reach areas directly beneath the bridge deck. This included areas that are often the most difficult for human inspectors to access safely.

Crucially, we also had to solve the problem of positioning. GPS signals often fail under the thick concrete of a bridge deck. We synced geolocation data directly to the camera images to compensate for any signal loss, ensuring that every photo could be accurately placed in 3D space.

Building the 3D model

Once the drone lands, the real work begins. We use a technique called photogrammetry, where software aligns thousands of overlapping 2D images to generate a 3D “skeleton” of points. This is then densified into a detailed point cloud, and finally, a textured 3D mesh, which is a solid, surface-mapped model of the bridge.

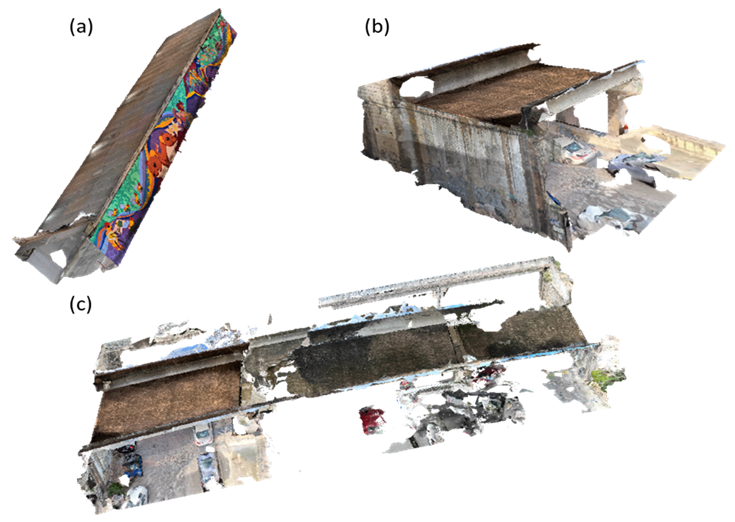

3D Mesh; (a) UM Bridge, (b) Partial St Julian’s Bridge, (c) Full St Julian’s Bridge.

3D Mesh; (a) UM Bridge, (b) Partial St Julian’s Bridge, (c) Full St Julian’s Bridge.The level of detail is significant. For the Msida bridge alone, 631 images were aligned to generate a 3D mesh consisting of over 42 million triangles. The San Ġiljan bridge, due to its length, was analysed in partial and complete sections, achieving alignment rates of 98% and resulting in meshes of up to 50 million triangles.

RELATED STORIES

The result is a high-fidelity virtual replica of the bridge that civil engineers can inspect on a computer screen, zooming in on specific sections without ever visiting the site.

From images to insight

In this virtual environment, we manually annotate visible cracks on the abutment walls and side decks. This data creates a precise inventory of defects, allowing us to measure them against international safety standards. We utilise benchmarks such as Eurocode 2 and EN 1504, which set strict limits for crack tolerance, to balance safety and aesthetics.

Annotating these cracks manually is still time-consuming, but it serves a secondary purpose: training Artificial Intelligence. By feeding these annotated images into the software that we are developing, we are teaching the system to recognise the specific visual patterns of concrete cracks. Theoretically, this paves the way for fully automated detection. In the future, a drone could fly over a bridge, process the data, and automatically flag areas of concern to the engineers, significantly reducing the “human error” factor.

Sample of the annotation of cracks (in yellow) used to train and test the AI model.

Sample of the annotation of cracks (in yellow) used to train and test the AI model.Democratising inspection

One of the most important findings of the DiHICS project is that it reduces the need for prohibitively expensive equipment to achieve these results. We found that even a basic setup with a commercial drone and a standard high-resolution consumer camera can yield professional-grade 3D models. This democratises the technology, making it accessible not only to large engineering firms but also to smaller maintenance agencies.

While the results are promising, this is not a magic fix. Real-world environments are messy. Obstacles such as trees or dangling wires can block the drone’s view, leading to gaps in the 3D model. Furthermore, processing 42 million data points requires significant computational power.

However, the project demonstrates that we can shift infrastructure monitoring from a reactive approach, fixing things when they break, to a proactive, data-driven strategy.

The DiHICS project offers a timely solution for regular, detailed, non-invasive monitoring that identifies problems early, when repairs are more straightforward and cheaper. This approach promises not only to save time and money but to become more proactive with how we care for our infrastructure.

Prof. Ing. Carl James Debono is the Dean of the Faculty of ICT and Principal Investigator of the DiHICS project.