This article does not assert that the Israeli–Palestinian conflict has polarized the West; that reality is already evident. It reworks the strategic framing of the conflict so that Western politicians can use it. This change didn’t happen on its own, and what happened on the ground can’t fully explain it. Instead, important parts of the conflict were slowly taken out of their political, historical, and geographical contexts and turned into a universal moral test. What looks like anger coming out of nowhere is really the result of a framing strategy that has been building up over time. The war itself didn’t change in any big way. But the language, rewards, and symbolic meaning that came with it did. The code became more important than the fight.

This reconstruction does not rely on conjecture or claims of centralized control. It uses ideological texts, speeches given in schools, institutional incentive systems, and comparisons of conflicts in different parts of the world. The goal is not to say that there is a conspiracy, but to show how strategic logics move, change, and become part of systems that let them in. In this context, strategy emerges from persistent patterns rather than covert collaboration. When universities, NGOs, media ecosystems, and activist movements start to have similar moral frameworks, they become easier to study. This article examines discourse as infrastructure rather than emotion. It looks at how that infrastructure was built.

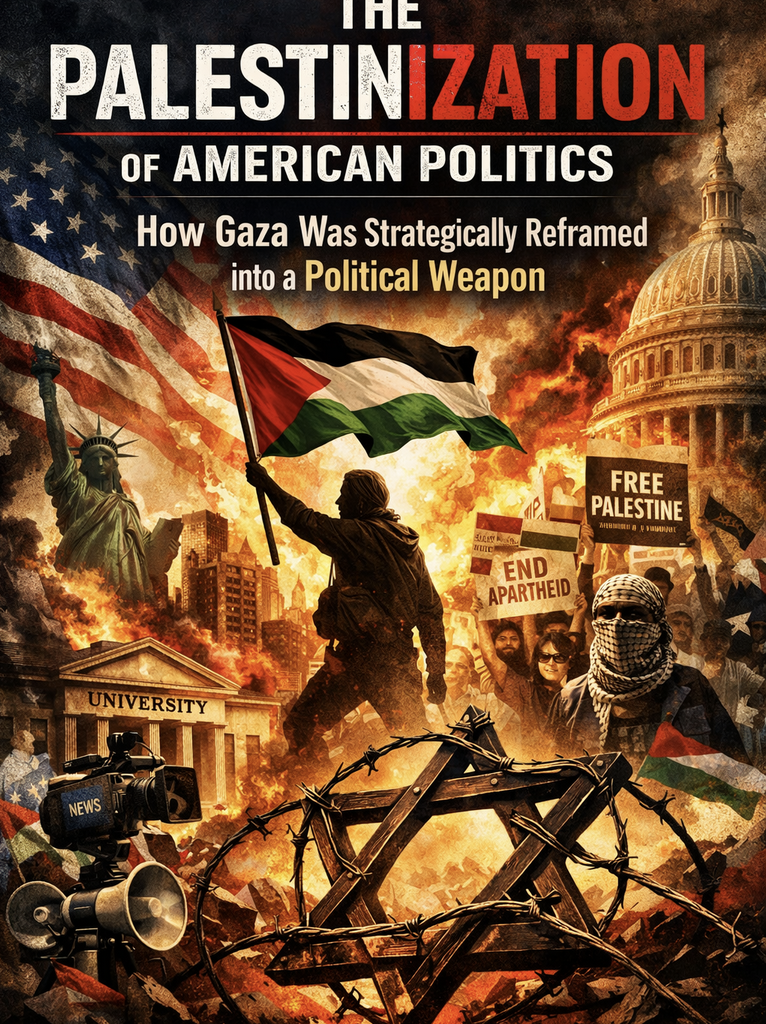

Dalia Ziada, an Egyptian writer and political analyst, says that what we are seeing is not just young people being activists or radicals. She calls it the “Palestinization of Western politics,” and that’s what happened. This process turns the Palestinian cause into a symbol that people in democratic societies far away from the Middle East can use and that they can’t argue with. Its goal is not to find a solution but to get people to act, not to live together but to force them to. In this context, people often think of Israel as a moral idea rather than a real country, and Jews are sometimes seen as stand-ins for power instead of a diverse group of people. When this change happens, debate becomes a set way of accusing someone. At that point, going against the grain becomes more socially risky.

Palestinization is the act of taking a foreign conflict out of its political and territorial context and making it a moral key for civilization. This key is supposed to make people angry and less likely to look into things. In this context, Gaza often serves not only as a geographic location but also as a symbolic catalyst that prompts automatic moral judgments. A lot of people see Israel as a sign of guilt rather than a political player. Regardless of belief, nationality, or dissent, there is only one political interpretation of Jewish identity. Moral complexity is supplanted by moral choreography. The outcome is not comprehension but coerced adherence.

Palestinization does not include all types of Palestinian advocacy, and it does not make the suffering of Palestinians any less real. It means using the cause in a certain way as a way to enforce morals in some Western activist and institutional settings. This difference is important because the strategy’s strength comes from its ability to protect itself from criticism by making analysis cruel. If people think the cause is sacred, they might think that questioning it is mean. Instead of trying to convince people, alignment now means expecting them to do something. This is how a political issue turns into a test of identity. And this is how it costs society to disagree.

For ground-breaking analysis, you need proof of intent, not just an interpretation. According to Ziada, ideological texts and public speeches are proof, but that doesn’t mean that there is centralized operational control. At an Al-Quds conference in 2002, the late Yusuf al-Qaradawi spoke very clearly about a strategic framework. Qaradawi said that Muslims come together because of causes, not race or culture. He also said that Palestine should stay the center of Islamic thought until Al-Aqsa is free. He didn’t just think of this as a goal; he thought of it as his duty. His audience was not just in the Middle East. He was directly speaking to Muslims who live in the West.

Qaradawi’s importance was not small or limited. He was one of the most powerful Sunni Islamist leaders in the world at the time, and the media in Qatar helped him reach even more people. He told his followers in later talks and writings to use the Palestinian cause to make friends with non-Muslim groups like academics, progressives, and civil society groups on purpose. The goal was to bring people together strategically, not to convince them of a religious belief. Qaradawi contended that political Islam would not progress in the West as a doctrine. It would move forward through translation, by becoming part of language that is humanitarian and anti-colonial. This continuity does not mean centralized control; rather, it means that a strategic logic has survived its creators.

To comprehend the strategy, it is essential to analyze what did not yield analogous outcomes. There are a lot of brutal and morally important conflicts going on in the world right now. Many of them have to do with war crimes, occupation, or mass displacement. In Ukraine, Taiwan, Sudan, Yemen, and Syria, many civilians are suffering. But none of these wars have divided Western societies as much as the one in Gaza. They have not consistently generated widespread campus occupations, ideological loyalty assessments, or moral purges. They haven’t been fully brought into domestic identity politics either. This difference needs to be explained.

Gaza was especially good at using this framing strategy. In Western discourse, it could be turned into a simple oppressor-oppressed binary based on race. It could be turned into a holy battle with cosmic stakes. It could be visually condensed into images that move around and often work on their own, without any context. Most importantly, it could change from a temporary political fight into a lasting moral identity. What cannot be converted into moral identity struggles to sustain mass mobilization. Gaza could. That ability to change is one reason it became the center of attention.

When Palestinization takes hold, the moral structure often becomes unbalanced. One side is mostly defined by pain and has no power. The other is mostly based on guilt and doesn’t have any historical context. Evidence is secondary because moral conclusions are often presupposed. Intent becomes insignificant due to the assumption of harm. People say that context is propaganda, not information. When one side is effectively free from moral judgment, asymmetry turns into war.

This structure helps make sense of a number of patterns that would otherwise be hard to understand. Sometimes, people allow chants calling for Israel’s destruction as a way to show their sadness. Activists are increasingly seeing Jewish institutions as valid targets for protest instead of just safe spaces for minorities. Sometimes, Jewish students are seen as politically suspicious just because they are Jewish, no matter what they believe or do. Violence is put into context, made to look good, or excused in ways that are not acceptable in other places. The rule is not always the same, but it happens a lot. Many other rules are relaxed when Gaza is the main issue.

One of the more uncomfortable conclusions of Ziada’s analysis is that many Western institutions unintentionally made this process stronger. More and more, universities in many countries saw moral absolutism as serious thinking and activism as scholarship. Some NGOs discovered that narratives driven by outrage consistently secured funding and visibility. Media ecosystems that were designed to get people emotionally involved brought out the most divisive frames. Bureaucracies for diversity and inclusion often turned global conflicts into racial binaries that didn’t work well with the complexity of being Jewish.

At the same time, criticism of political Islam was often changed to “Islamophobia,” which made it socially dangerous to question ideas. At the same time, hatred of Jews was sometimes called “anti-colonial resistance,” especially after Israel was declared to be uniquely illegitimate. These changes weren’t the same everywhere, but they made each other stronger where they happened. Most institutions thought they were protecting justice. In practice, they sometimes used moral language to hide their ideology. The result was in line with the incentives.

These changes are happening more and more often, but not all the time. Synagogues have been called “protest sites” instead of just being seen as safe places for religious people. In some institutional settings, Zionism has been redefined as racism, regardless of historical or national differences. Jewish students have been told, either directly or indirectly, that they must not support Israel in order to be neutral. Calls for ceasefires have been made along with calls for erasure. Institutional statements have denounced “violence” without identifying the offenders or the underlying causes. People have often seen Jewish fear as a problem instead of proof. The pattern doesn’t need any extra decoration. The point is that it happens again.

Dalia Ziada saw this pattern early on, not because she is controversial, but because she knows how Islamist political strategy works from the inside out. She knows that it can change, that it takes a long time, and that it likes to have an indirect effect. Western analysts, who are used to seeing activism and identity politics, often miss ideology when it pretends to be morality. Ziada does not. She views the Palestinian cause not as an emotion but as a vector.

Her framework does not anticipate every result or elucidate every participant. It does, however, shed light on the main path of conversation and institutional alignment. Ziada’s warning is based on history and is very specific. Anti-Americanism and anti-liberalism often come after antisemitism becomes normal. The same framework that denies Jews the right to self-determination also tends to reject secular law, pluralism, and free inquiry. Israel is not the end. It is often the first step.

This strategy’s last illusion is that it is mostly about peace or making a Palestinian state. It is not in many cases. Peace necessitates compromise, acknowledgment, and political resolution. Palestinization relies on ongoing grievances and moral escalation. A settled conflict would diminish the cause’s ability to mobilize. Delegitimization keeps it alive.

This helps to explain why maximalist slogans are so popular. It helps us understand why people often say that concessions aren’t enough. It helps explain why ceasefires are rarely seen as the end of a conflict and why negotiations are seen as betrayal. Gaza must stay on fire, both in real life and in stories. The fire keeps people’s attention. The strategy loses power without it.

This strategic reframing has already changed some parts of Western moral language. It has made taboos less clear, made differences less clear, and pushed institutions to reward ideological certainty over inquiry. If this trend keeps up, Jewish life in Western democracies may rely more on political disavowal than on equal protection. Future conflicts may be pre-framed into moral binaries before facts are established. Liberal democracies might keep the language of pluralism but not use it.

It is clear that the tragedy in Gaza is real. It is also possible to see the instrumentalization of Gaza. It’s not empathy to mix the two up. It is giving up. You can’t unsee the code once you see it.

al-Qaradawi, Yusuf. [Address at the Al-Quds Conference on Palestine as a unifying cause for the Muslim ummah]. Al-Quds Conference, 2002.

Ziada, D. (2025, November 19). Speech at ISGAP conference on the Muslim Brotherhood threat to U.S. national security [Video]. X.