The Kurds, an ethnic group spanning Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Armenia, constitute one of the world’s largest stateless populations. Historically subjected to systemic persecution, many Kurds have been driven to seek refuge abroad, including in Japan. In Kawaguchi City, a Tokyo suburb of approximately 600,000 residents, a community of several thousand Kurds has established a significant presence.

While this enclave was once referred to sympathetically as “Warabistan” (a portmanteau of Kurdistan and the local Warabi Station), public sentiment has shifted dramatically. Since 2023, the community has transitioned from a symbol of multicultural curiosity to a primary target of xenophobic discourse in Japan.

Prior to this period, Kurds were referred to almost exclusively in relation to Middle Eastern affairs, such as the Syrian civil war and Turkish politics. Although public interest in Kurds within Japan was limited, they were generally portrayed as individuals fleeing persecution who nevertheless faced significant difficulties in Japan due to their inability to obtain refugee status.

However, 2023 marked a turning point as Kurds increasingly became targets of hate speech and racial harassment. This shift was precipitated by the June 2023 revision of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, which facilitated the deportation of asylum seekers, leading to Kurds being labeled “bogus refugees.”

Simultaneously, the right-wing members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party passed a resolution in Kawaguchi calling for strengthened crackdowns on crimes committed by “some foreigners,” a measure widely interpreted as implicitly targeting Kurds. The situation escalated further in July 2023, after a localized hospital incident was reported by the Sankei Shimbun under the headline “Kurds mobbed, citizens frightened,” a narrative that was repeatedly weaponized to suggest a community-wide propensity for violence. Although these incidents were isolated, their close temporal proximity and sustained amplification contributed to the broader criminalization of Kurds in Japan.

Media Amplification and Online Mobilization

The heightened hostility is reflected in a dramatic surge in media coverage and digital engagement. Data indicates that while center-left outlets like the Asahi Shimbun maintained a relatively stable or sympathetic tone, the right-wing Sankei Shimbun saw an unprecedented spike in Kurdish-focused content, rising from just eight articles between 2020 and 2022 to 213 after 2023.

This contrasts sharply with the center-left Asahi, which ran 63 and 112 articles during the same periods, respectively. Newspapers other than Sankei, including the conservative Yomiuri, have fundamentally maintained a neutral or sympathetic tone toward Kurds. This comes in contrast to Sankei’s relentless negative campaign against Kurds. Far-right journalists have also intensified their efforts, with four books targeting Kurds published since 2024.

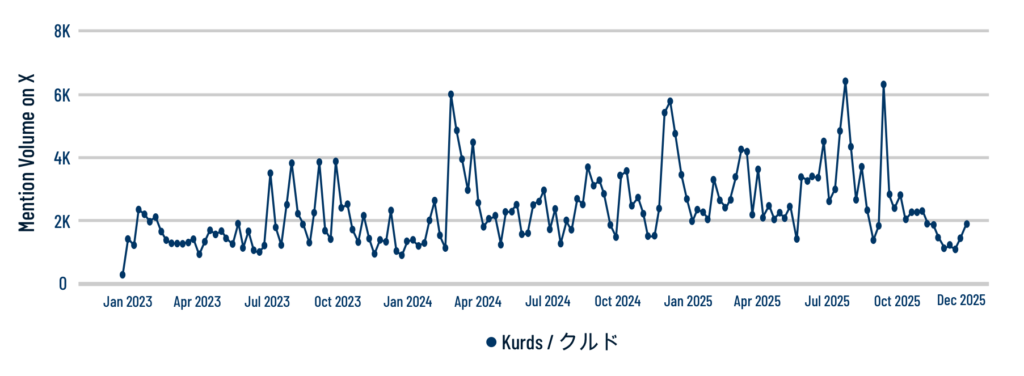

This media blitz was mirrored online, where the number of mentions of Kurds rose sharply starting in July 2023. This pattern suggests that anti-Kurdish sentiment has moved beyond a local grievance in Kawaguchi to become a nationalized issue for the Japanese far right. At least seven hate groups, such as Hinomaru Gaisen Club, Nippon Daiichi-to, Tsubasa no To, Kawaguchi Jikeidan, Nihon Yamato-to, Gaikokujin Hanzaisha Bokumetsu Undo, and Nippon Shinryaku wo Yurusanai Kokumin no Kai, have since mobilized in the area, repeatedly organizing physical anti-Kurdish demonstrations.

Frequency of Japanese-language mentions of Kurds on X over time

Hate at the Intersection

Demonstrably, Kurds have become a central target of anti-immigrant hate speech in Japan. Yet, the number of registered Turkish nationals, including Kurds, stood at just 7,711 nationwide as of December 2024, and even when accounting for undocumented residents, the total does not exceed 10,000. Given the small size of this community, the intensity of the backlash raises a critical question: why have Kurds borne such a disproportionate share of hostility?? This disproportionate targeting can be attributed to the intersection of several key factors that shape the Kurdish experience in Japan.

Kurds began migrating to Kawaguchi City in the 1990s, and it is estimated that a quarter of Turkish nationals in Japan, including over half of the Kurdish population, now reside in this area. Many Kurdish men work in the demolition industry, with Kurdish entrepreneurs owning roughly 70% of the demolition companies in the region.

While the demolition industry provides a vital source of income for many Kurds, it also exposes them to hate. Demolition companies rent material yards within Kawaguchi City, and the constant truck traffic to and from these yards is often perceived as a nuisance by local residents. This issue is all-too-common and rooted in social class, as Kurdish men gravitate towards physically demanding and low-wage labor. Yet this economic reality is often misinterpreted and weaponized to portray them as “troublesome Kurds.”

Furthermore, among the 73% of the 1,458 Turkish nationals registered in Kawaguchi City, men make up the majority. Because women are often not formally employed, men tend to be more visible in public spaces, a gender imbalance that hate groups have actively exploited.

There has been a proliferation of hateful graphics targeting Kurds online, including a fabricated, AI-generated image of angry Kurds bearing a sign displaying the text “the Japanese should get out of Kawaguchi.” The image, which notably only depicts men, garnered approximately 713,000 views on X.

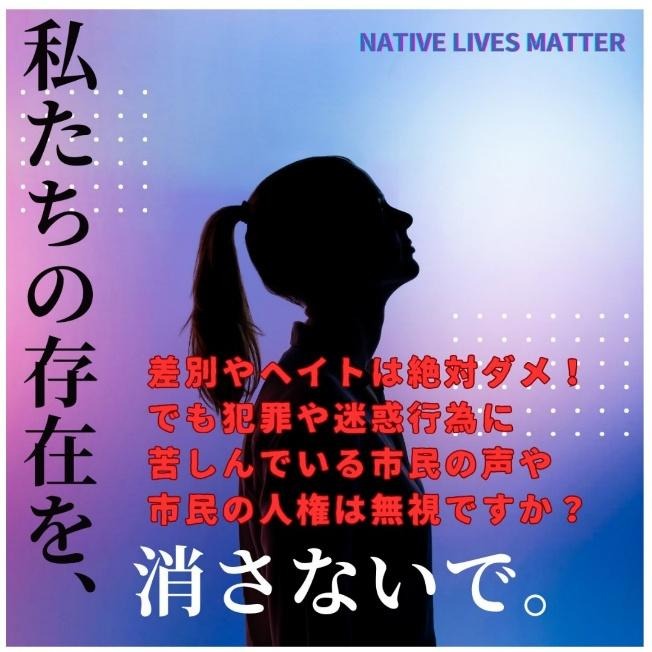

Seiichi Okutomi, a far-right member of the Kawaguchi City Assembly, shared another graphic with text: “Native lives matter! No to discrimination and hate! But do you ignore citizens’ voices and human rights suffering, crimes, and harassments?” which received approximately 357,000 views on X and was later featured in an article published by Sankei. The graphic portrays Japanese women as victims of crime and harassment. Sankei has repeatedly reported on a single rape case involving a Kurdish man, persistently framing Kurdish men as inherently violent and threatening.

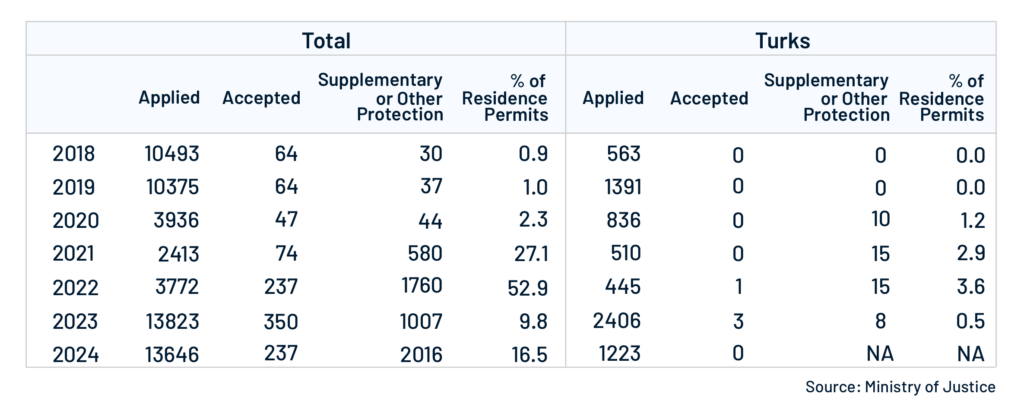

Hate groups have also capitalized on the fact that many Kurds submit multiple refugee applications after arriving in Japan, portraying this practice as an “abuse” of the country’s asylum system. The reality is that Japan is widely recognized for its extremely low refugee recognition rate, as shown below. Although the number of recognized refugees increased in the 2020s, the rise was driven primarily by applicants from Myanmar and Ukraine, while recognition rates for other nationalities have remained largely unchanged.

For Turkish nationals, who are predominantly Kurds, only four individuals have ever been recognized as refugees, and granting residence status on humanitarian grounds remains exceedingly rare. Even cases that would likely receive protection in other countries are often rejected in Japan. Although a provisional visa is typically granted during an initial refugee application, subsequent applications are frequently denied. As a result, approximately one-third of Kurds living in Kawaguchi City are stuck in an irregular status, a condition that substantially heightens their vulnerability.

Number of refugee applicants in Japan

Number of refugee applicants in Japan

Manufactured Crisis and Far-Right Convergence

Notably, Islamophobia has not been the primary mobilizing frame in Kawaguchi, in part because Kawaguchi City lacks a mosque and because Kurds do not engage in large-scale public religious gatherings, such as Eid celebrations or Friday prayers. Instead, hostility toward Kurds has been amplified through the intersection of race, class, gender, and irregular status as explained above. Consequently, the relatively small Kurdish community, numbering only a few thousand, has been discursively constructed as bandits who disturb the peace and order of Kawaguchi City.

Most concerning is the far right’s demonstrated capacity to manufacture a social problem where none existed. Far-right local politicians submitted resolutions to the neighboring Kawasaki City Assembly, a far-right journalist emerged as a central influencer amplifying the issue, and a media outlet sustained a negative narrative. Hate groups then translated this discourse into repeated physical mobilization.

These coordinated actions, initiated and sustained by far-right actors, demonstrate that the convergence of political, media, and street-level mobilization can effectively demonize even small and marginalized communities such as the Kurdish population.

Japanese hate groups have long targeted ethnic Koreans who migrated to Japan before and during World War II, illustrating how the far right in Japan has been historically embedded within East Asian geopolitical structures. The recent expansion of hostility toward Kurds, however, represents not merely a continuation of this pattern but a qualitatively distinct form of hatred that increasingly converges with Western far-right ideologies.

This shift is further reflected in electoral outcomes: in the July 2025 Upper House election, the far-right Sanseito party, campaigning on a “Japanese First” platform, secured the third-largest share of votes in the proportional representation bloc. Sanseito’s electoral gains mark the first time an anti-immigrant party with a stated commitment to restricting the rights of foreign residents has gained mainstream acceptance in Japan. This development can be understood as evidence of the transnational diffusion of far-right ideology, with anti-Kurdish sentiment potentially serving as a harbinger for future xenophobic mobilization.

(Naoto Higuchi is a professor of sociology at Waseda University and the author of the forthcoming book The Digital Rise of the Far Right in Japan, co-edited with Yuki Asahina (Manchester University Press).

Nanako Inaba is a professor of sociology at Sophia University and the organizer of a scholarship project supporting undocumented high school students.)