It is predicted that two-thirds of polar bears will become extinct by 2050 due to the effects of global warming. However, a study published in December 2025 by researchers at the University of East Anglia in the UK indicated that factors involved in regulating polar bear gene expression may be changing in order for polar bears to respond to the environmental stress of global warming. This high ability to adapt to climate change at the genetic level may also have an impact on future extinction risk assessments.

Diverging transposon activity among polar bear sub-populations inhabiting different climate zones | Mobile DNA

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13100-025-00387-4

Polar bears are adapting to climate change at a genetic level – and it could help them avoid extinction

https://theconversation.com/polar-bears-are-adapting-to-climate-change-at-a-genetic-level-and-it-could-help-them-avoid-extinction-269852

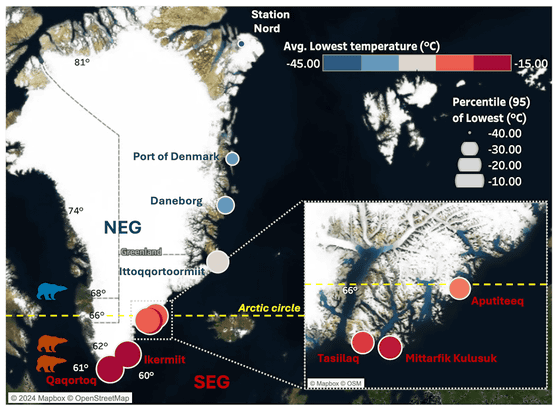

Recent research has revealed a large temperature difference between the northeastern and southeastern regions of Greenland, where polar bears live. Furthermore, while the northeastern region is covered with Arctic tundra, the southeastern region is covered with forest tundra, experiencing a harsh environment with heavy rainfall and strong winds. Modeling studies suggest that the polar bear population in the southeastern region is likely to decline by more than 90% within 40 years. The figure below visualizes temperatures along the coast of Greenland, where polar bears live, using data from the Danish Meteorological Institute.

A research team led by Alice Godden, a senior researcher in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of East Anglia, compared genetic data from blood samples of 17 polar bears living in northeastern and southeastern Greenland. By analyzing the RNA sequences of genes, they were able to determine which genes were activated in response to climate change and explore how environmental changes affect the ecology of polar bears.

The genetic analysis focused on

transposons (TEs), also known as ‘jumping genes’ because they move their genomic location within cells. TEs are normally repressed, but are prone to activation under environmental stress, potentially altering the expression of other genes. While 45% of human genes are made up of TEs and some plants have over 70% of their genes, polar bear genes are approximately 38.1% made up of TEs.

The analysis found that the warmer climate in southeastern Greenland caused a massive activation of TEs throughout the polar bears’ genomes. Furthermore, the altered TE sequences were more abundant in younger, more abundant southeastern polar bears than northeastern polar bears, and more than 1,500 TEs were ‘upregulated,’ indicating genetic changes that may help polar bears adapt to rising temperatures.

The researchers also found that TE changes may affect genes involved in heat stress, metabolism, and aging, suggesting that polar bears are adapting to warmer environments. Additionally, they found TEs that were activated in genomic regions involved in fat processing during times of food scarcity. This may indicate that polar bears in the northeast primarily feed on blubber-rich seals, while those in the southeast are adapting to a plant-based diet found in warmer regions.

‘This discovery suggests that polar bears may have mechanisms for adapting to extreme environments. However, this does not necessarily mean that the species as a whole faces a lower risk of extinction. Future research should explore other polar bear populations living in more severe climates to understand how polar bears adapt to extinction risk and survive, and which populations are most at risk,’ said Godden.