A new Slovak criminal law linked to the post-war Beneš Decrees has triggered protests among Slovakia’s Hungarian minority, criticism from Hungary’s opposition, and a diplomatic escalation involving a potential future Hungarian prime minister.

Péter Magyar, leader of Hungary’s opposition Tisza party and the strongest challenger yet to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, has warned that a future Hungarian government led by him would respond with the “strongest possible diplomatic measures” if Slovakia does not change course. He has even suggested expelling Slovakia’s ambassador from Budapest.

The law in question was signed by President Peter Pellegrini shortly before Christmas, published on 27 December and entered into force immediately. It introduces a new criminal offence penalising the denial or questioning of the Beneš Decrees.

Why the Beneš Decrees still matter

The Beneš Decrees refer to a series of presidential decrees issued in 1945–46 by Edvard Beneš, then president of Czechoslovakia. They provided the legal basis for the confiscation of property and the loss of citizenship of ethnic Germans and Hungarians after the Second World War, based on the principle of collective guilt.

While widely considered part of history, some of their legal effects remain relevant in Slovakia, particularly in property disputes. In recent years, Slovak authorities have continued to rely on the decrees in retroactive land confiscation cases affecting descendants of ethnic Hungarians, keeping the issue politically sensitive both domestically and in relations with Hungary.

The latest amendment was adopted after the opposition party Progressive Slovakia (Progresívne Slovensko, PS) called on the government, during a tour of southern Slovakia focused on issues facing the Hungarian minority, to ensure that the Beneš Decrees could no longer be used as a legal basis for land expropriations.

The governing coalition has argued that PS was seeking to “open” the Beneš Decrees themselves, a claim the party rejects, saying it was calling only for an end to their continued practical application in property cases.

Related article

In Slovakia’s south, property disputes reopen a painful past

Read more

Before signing the amendment, President Pellegrini was urged to veto it by György Gyimesi, a former MP known for opposing the continued use of the Beneš Decrees, according to Denník N. In an open letter, Gyimesi reminded the president that ethnic Hungarians had played an important role in his election. Gyimesi is currently an adviser to Environment Minister Tomáš Taraba of the nationalist SNS party, who was the first member of the Slovak government to propose criminalising the questioning of the Beneš Decrees.

Criminal law change sparks backlash

The new amendment to Slovakia’s Criminal Code makes it a criminal offence to deny or question the Beneš Decrees. Critics argue the wording is vague and could restrict freedom of expression, including academic debate, journalism or political discussion.

Opposition parties and General Prosecutor Maroš Žilinka have both challenged the amendment at Slovakia’s Constitutional Court, arguing it is poorly drafted and incompatible with constitutional protections.

For Slovakia’s Hungarian minority — numbering roughly 450,000 people — the change is seen as an attempt to silence discussion of historical injustices that still have real-world consequences.

Protests in southern Slovakia

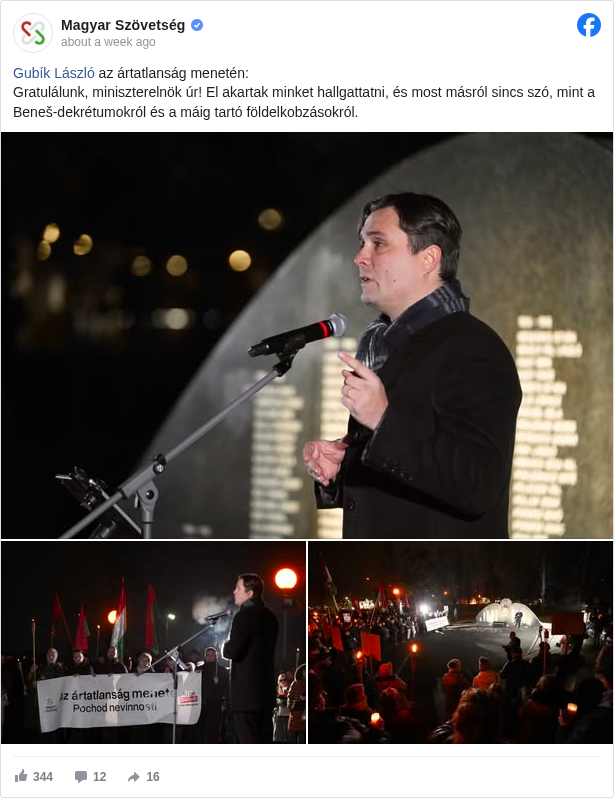

The issue has mobilised Hungary’s ethnic kin in Slovakia. On 20 December, around 300 people joined a protest march in Dunajská Streda, a town in southern Slovakia with a majority Hungarian population. The demonstration, organised by the Hungarian Alliance party under the title The March of Innocence, protested against the criminal-law amendment and warned of further action.

Party leader László Gubík said the amendment could criminalise historians, filmmakers or citizens who openly discuss post-war expulsions and property confiscations. He warned that if the law remains in force, the party could consider civil disobedience alongside legal challenges and international pressure.

The protest began at a memorial to Hungarians expelled after the war and ended with speeches condemning what organisers described as an attack on free expression and legal certainty.

The presence of representatives of Hungary’s far-right Mi Hazánk party, as well as nationalist slogans referencing the Treaty of Trianon, underlined how easily the issue can slide from minority rights into broader nationalist symbolism — something Hungarian minority leaders in Slovakia have sought to avoid.

The Hungarian Alliance has also announced a conference titled “Through the Prison Window?”, scheduled for 22 January, Hungary’s Day of Culture. The event is intended to focus on freedom of expression, property rights and legal certainty in relation to the Beneš Decrees, according to Denník N.

Magyar challenges both Bratislava and Budapest

Péter Magyar has used the controversy to criticise Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico, calling him “openly anti-Hungarian”, but also to attack Viktor Orbán for what he describes as passivity.

In December, Magyar accused Orbán of having “left Hungarians in Slovakia to their fate”, a notable intervention from an opposition leader who rarely comments on foreign policy. After the law entered into force, his rhetoric sharpened further.

“If Slovakia keeps legislation that collectively punishes the Hungarian minority and threatens people with prison, then Slovakia’s ambassador has no place in Hungary,” Magyar said, adding that a Tisza government would act decisively in line with EU law.

With parliamentary elections due in Hungary in the spring and opinion polls suggesting Tisza leads Orbán’s Fidesz party, Magyar’s statements carry weight beyond opposition rhetoric.

Hungarian government takes cautious line

By contrast, the Orbán government has responded carefully. Prime Minister Orbán said Hungary first needed to analyse the Slovak law, noting that Hungarian law does not recognise a general ban on “questioning” historical events, apart from Holocaust denial.

Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó said Budapest had been assured by Slovak officials that the legislation was not aimed at the Hungarian minority, while also promising that Hungary would use all available political and legal tools to prevent harm to ethnic Hungarians in Slovakia.

A more critical tone came from senior Fidesz MP Zsolt Németh, who described Slovakia’s approach as unacceptable but stressed that Hungary does not want to interfere directly in Slovak domestic politics.

“We consider it particularly problematic that land continues to be expropriated on the basis of the Beneš Decrees,” Németh told Napunk. “In our view, this is incompatible both with the long-term coexistence of Hungarians and Slovaks and with the legal certainty to which Hungarians in Slovakia are entitled.”

In the past, Fidesz politicians have spoken very sharply about the Beneš Decrees. In 2021, the Speaker of the Hungarian Parliament, László Kövér, described what was done to the Hungarian community in Slovakia between 1945 and 1947 as “a crime before God and before mankind”.

Issue moves to European level

The controversy has also reached the European Parliament, where opposition Hungarian MEPs have argued that both the continued application of the Beneš Decrees and the criminalisation of their criticism contradict EU principles of the rule of law and freedom of expression.

Meanwhile, a civic protest has been announced outside the Slovak Embassy in Budapest on 3 January, organised by non-partisan activists who say they want to defend European values and free debate.

Legally, the fate of the Slovak amendment now lies with the Constitutional Court. Politically, however, the damage is already done. A domestic criminal-law change has evolved into a regional dispute, entangled with Hungary’s election campaign and long-standing historical grievances.