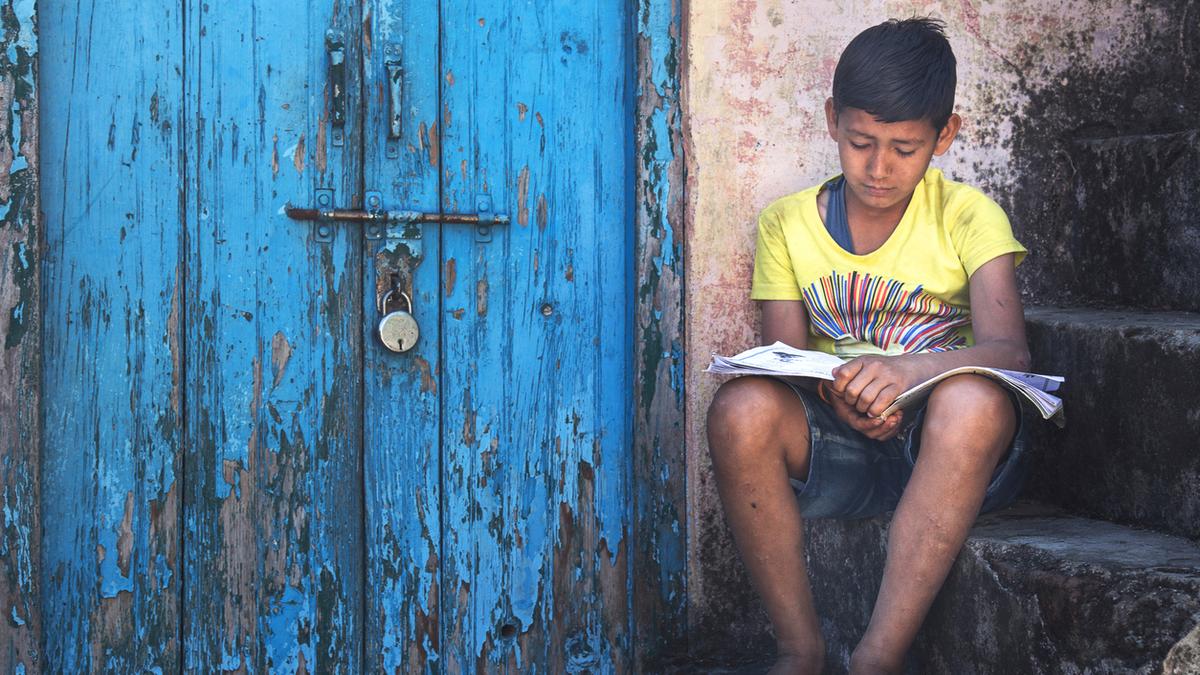

In several Indian cities, night shelters, bridge school programs, and seasonal hostels have been created to reach out to the children who cannot avail regular schooling due to homelessness, migration, or economic compulsion. Although these initiatives have shown success in patches, serious questions persist about their scalability, integration into formal schooling, and long-term effects.

Under the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009, free education is guaranteed to all children between six and 14 years. The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan goes a step further by urging targeted strategies for migration-affected children, including seasonal hostels and special training to help retain them in age-appropriate classes.

However, education departments and civil society alike recognise that no single programme offers a comprehensive solution to the barriers faced by children on the margins.

Night shelters: Safe spaces with limited educational reach

Night shelters or shelter homes are typically run by municipal bodies or in collaboration with Ngos, to provide food and safety to homeless children and adults. For instance, in Delhi, the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) through partners like SPYM operates dozens of shelters which provide service to thousands of homeless children and adults with basic amenities and non-formal education support.

When asked about the education initiatives in night shelters, Ramniwas Dy. Director (NIGHT Shelter DUSIB) shared that the department’s primary responsibility is to provide shelter and food (three times a day) to the children and adults staying there. We have 153 males, 17 females and 19 families with children in the shelter. The objective, he said, is to create a safer environment to accommodate families who are homeless and need help.

He added that while the Social Welfare Department and NGO occasionally helps to connect children for education outreach, they are not a replacement for full-time schooling. A local NGO educator who works with shelters shared that night shelters have no structured or sustained scheme to educate children with the shelter system. He added that there is no formal education enrollment mechanism, and many families either move or send their children to work, showing no such interest in the education of their children.

Officials said that shelters help build trust and stability, but a general lack of structured academic time limits substantive learning.

Bridge schools: A step toward integration?

India aspires to be a developed nation by 2047, and that largely rests on strengthened human capital through quality education. Despite several reforms like NEP 2020 and NIPUN Bharat, though learning gaps have marginally improved, they still persist on a large scale as flagged by ASER, PARAKH.

Of the estimated 47.44 million out-of-school children in the age group of 6-17 years in India, 16.8% are reported by the Ministry of Education on December 30, 2024, according to UDISE+ data for 2023-24. These numbers comprise those who have never been enrolled and dropouts. The data indicates that these statistics pose serious challenges to meeting universal enrollment goals envisaged under NEP 2020, with dropout rates higher at the upper-primary and secondary levels.

Bridge schools are planned to serve as transition learning spaces for out-of-school children, migrants, or those who missed earlier years of schooling. Such programs compress foundational content for learners to enter age-appropriate classes in mainstream schools.

Organisations such as Samridhdhi Trust and Help2Educate establish bridge programs in urban slums and migrant settlements, using multilingual instruction adapted to the children’s prior learning levels. Together, these kinds of initiatives have identified and educated thousands of youngsters, facilitating the entry of many into formal schools after a year of intensive learning.

Sanjay Kumar Yadav, Block Education Officer (Rural), Delhi, said the department follows a multi-pronged approach to identify and enrol migrant and out-of-school children in rural areas. Children are identified through door-to-door household surveys, awareness initiatives such as School Chalo Abhiyan, educational fairs.”

“No child is denied admission due to lack of any documents. As per the Right to Education Act, address proof, Aadhaar or TC are not mandatory at the time of education. Schools accept self-declarations or local verification and later assist parents in completing documents.” he added

When asked about the migrant and out-of-school children, he said, “These children are tracked separately in enrolment data, allowing schools to provide targeted support, monitoring and flexible admission to ensure continuity of education. Rural schools often deal with migration due to child labour, poverty, and job between villages or districts.

Skand Gupta, Education officer (Urban), “Under the Urban Education Department, we are working on a large scale for homeless children and juvenile offenders with two different sections of education. For each sector, more than 50 children are enrolled, and two teachers are deputed under the scheme. These teachers come from different government schools after regular school hours and impart education to every child irrespective of their background. Our aim is to make these children literate by providing them subject knowledge and a foundation for formal education.”

However, most such children are unable to enroll in regular schools because they lack identity documents and face legal requirements regarding Aadhaar and Permanent Education Numbers. Despite these constraints, we are making every possible effort to ensure continuity in learning. Going forward, establishing dedicated schools up to Class 8 within shelter homes, along with skill development, would help address mainstream integration issues and enable such children to become self-reliant.” he added.

Parvati Kanwar, a child rights activist, also brought nuance into the debate, saying, “Bridge education shows potential, but without mechanisms that guarantee admission and retention in formal schools, its impact tends to be short-lived.”

She mentioned that though the government policies guarantee free education for all children below 14 years under the RTE Act in government schools, many children continue to drop out because they are forced into begging and child labour.

Ms. Kanwar said that several such children have been rescued and sent back to their home states, where they were produced before the Child Welfare Committee and placed in shelters through District Child Protection Units. Later, these children were enrolled in schools in coordination with the respective state governments.

She also pointed out the disturbing trend of many underage children providing fake Aadhaar cards for employment. Later, however, medical tests usually reveal the real age, indicative of the child labour and how the age-related protections are applied.

Seasonal hostels: Promising in concept, challenging in practice

Seasonal hostels are designed to keep the children of migrant workers in educational settings while their families are migrating for work. According to SSA guidelines, these are supposed to run through migration periods, keeping children in local schools rather than having them migrate with adults to work sites.

The number of out of school children increased from 28,139 in the last academic year to 31,068 in 2024, according to the latest survey conducted by the Haryana education department for the age group 7-14 years. The survey carried out in December 2023-January 2024, is for the academic year 2024-25.

On the ground: What practitioners see

Frontline providers — NGOs and child labour activists, recount how programmes often face practical limitations:

Anastassiya Savchenko, NGO Educator, Indian Women Impact (IWI), by Luminfinity Foundation, said, “For children living on the streets and migrant, school does not start with the enrollment paperwork, it starts with trust. In cities that prioritise survival, non-governmental organizations are connecting the policy with the child. Our duty is not merely to educate but rather to be a support for the kids during their difficult times, such as when they are moved, or when they are scared, or when they doubt themselves. The moment learning is paired with emotional safety, creativity, and acquiring skills for livelihood, the kids who once viewed education as a burden now start to see it as a future.”

Parvati Tanwar, Child Labour Activist, says, “For children who work or live without stable shelter, schooling competes with immediate economic needs. Even with outreach programmes, retention is a persistent problem.”

Many NGOs like Salaam Baalak Trust and Butterflies work directly with street and working children, offering informal education, life skills and pathway support into formal schooling. Yet, replicating these models at scale remains a challenge.

Night shelters, bridge schools, seasonal hostels, NGOs are working tirelessly to impart education to the children but all fall short when not integrated with mainstream education systems, lack robust tracking mechanisms, or fail to address underlying issues like housing instability and child labour.

Policy gaps and the way forward

Experts emphasise that programmes must be embedded within broader systemic frameworks:

Baila Srivastava, retd Government School, Principal, Government UPS Bandri Ka Naasik said, “Without flexible attendance norms, coordinated tracking and proactive support from education departments, these interventions remain adjuncts rather than solutions. The RTE Act and SSA guidelines articulate inclusive schooling and special strategies for migrant children, but operational gaps, particularly in urban contexts and among homeless populations, persist.

(Uttkarsha Shekhar is an independent journalist whose interests span defence, science, environment, education, entertainment and fashion.)

(Sign up for THEdge, The Hindu’s weekly education newsletter.)