Today the story would be unremarkable: two gay men, migrants from England, give their Queensland home a portmanteau of their last names.

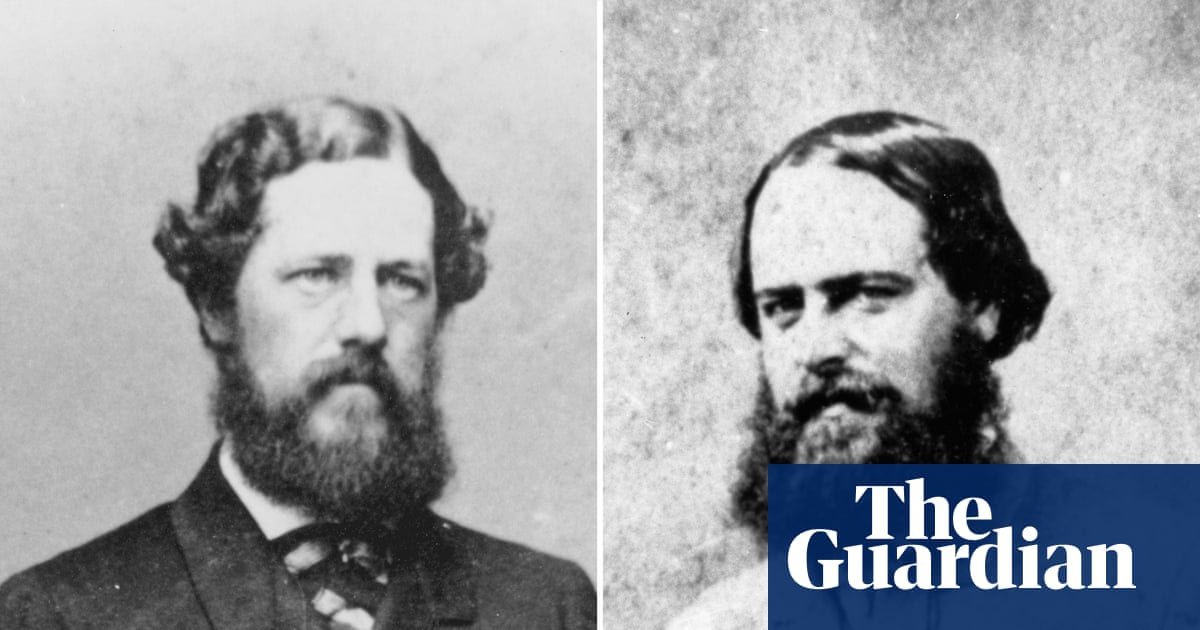

But in 1859, these two men, Robert Herbert and John Bramston, were the new state’s first premier (then called colonial secretary) and one of his attorneys general.

The name, Herston, was later used to name the modern suburb that covers the area, and in less than seven years, the suburb in Brisbane’s north will host the main stadium for the 2032 Olympic Games.

As the city takes the world stage, gay historians argue that the long-forgotten history of Herston should finally get the recognition it deserves.

The Herston story is recounted in the 2001 gay history of Queensland, Sunshine and Rainbows: the Development of Gay and Lesbian Culture in Queensland. Its author, Clive Moore, says he was not the only one to conclude that Herbert was in a gay relationship.

Herbert and Bramston met at Balliol College, Oxford, in the 1850s, and shared rooms there and in London.

Moore describes their lives as a “gay love story”, though it would have been impossible to admit such a thing publicly. Herbert never married and had no children.

In an 1864 letter to his sister, Herbert explained that marriage would risk “being wretched”, for a chance “of a little possible additional happiness”.

“It does not seem to me reasonable to tell a man who is happy and content, to marry a woman who may turn out a great disappointment,” the letter reads.

Herston, the house shared by Robert Herbert and John Bramston, has been demolished. It is now the site of the Royal Brisbane and women’s hospital. Photograph: State Library of Queensland

“There must be a lot of gay men today who have explained it that way to their sisters and mothers,” Moore says.

Herbert held his position until February 1866 and returned to England shortly afterwards, where he lived until his death in 1905.

Bramston also returned briefly to England, but was back in Queensland by 1868, and married Eliza Russell in Brisbane in 1872. He died in Wimbledon in 1921.

Herbert’s government showed an unusual degree of sympathy for gay men. Queensland was the first state in the country to remove the death penalty for the offence of male sodomy. NSW did not do so for two decades.

Moore argues their relationship was doubly unlawful, doubly secret, because it was within cabinet. Even then that was against the rules, he says.

The president of the Australian Queer Archives, Timothy Jones, says there were many people in influential positions throughout history thought to have been gay.

“Learning this history is super exciting for queer people today,” he says.

Jones is one of many in the gay community who believes their story should be told at the Olympics. There are 64 countries where homosexuality remains illegal, many of which participate in the Games.

But he cautions against lionising individuals simply because they are now thought to have been gay.

“We need to be careful about celebrating people in the past who lived closeted lives,” Jones says.

“We only know a limited amount about them, and they are ambivalent figures in perpetrating injustices of colonialism. But I think it’s a good opportunity to point to the progress that’s been made and what still needs to happen.”

The president of Brisbane Pride, James McCarthy, says the Olympics gives us “the opportunity to project the image of the confident and inclusive city that we all know Brisbane to be”.

“It is essential that LGBTQIA+ communities and histories are front and centre in the telling of Brisbane’s story,” he says.

When Moore moved to Queensland in the 1980s, his sexuality was unlawful. Gay school teachers were being threatened with the sack; Greg Weir, an openly gay trainee teacher was refused employment due to his sexuality. Homophobia in politics escalated at the end of the decade, part of a desperate attempt to distract from revelations of corruption in cabinet and the police, by the conservative government of Russell Cooper. He said a Labor government would bring a “flood of gays crossing the border from the Southern states”. There was even a proposal to extend the state’s laws to cover women for the first time.

In 1989, Queensland police laid some of Australia’s last charges under anti-gay laws. In 2017, the state government apologised and quashed a century and a half of recorded convictions.

Queensland’s first openly gay MP, Trevor Evans, was elected in 2016, 157 years after Herbert took office.

The Herston home is long gone – it is now the site of the Royal Brisbane and women’s hospital.

Herbert’s name lives on, but more prominently in far north Queensland, which boasts a Herbert river, a Herbert range, the town of Herberton and the federal electorate of Herbert.

In 1975, the Queensland Place Names Board approved the official naming of the Brisbane suburb as Herston. But there are no heritage sites in the area to commemorate the name, nor are Bramston and Herbert’s full names recognised anywhere in the suburb.

“It’s time Queensland faced up to a few things,” Moore says.

“The gay community knows about [Herbert and Bramston], but basically the straight community in Brisbane doesn’t know about it. It’s never been aired in a public sort of a way.”