For many in Pakistan, 2025 marked the end of a long period of its strategic isolation. The reasons are evident: an unexpected turnaround in US-Pakistan relations in the early months of the Trump presidency; a new energy in Pakistan-Saudi ties following the conclusion of a defence agreement; and a new relevance in the tangles of West Asia given the US interest in raising a multinational force to address new realities in Gaza. Underpinning this diplomatic momentum was the cloak of legitimacy the military and the govt in Pakistan accorded themselves through a carefully orchestrated narrative — that they had led the country into successfully standing up to India in May 2025.

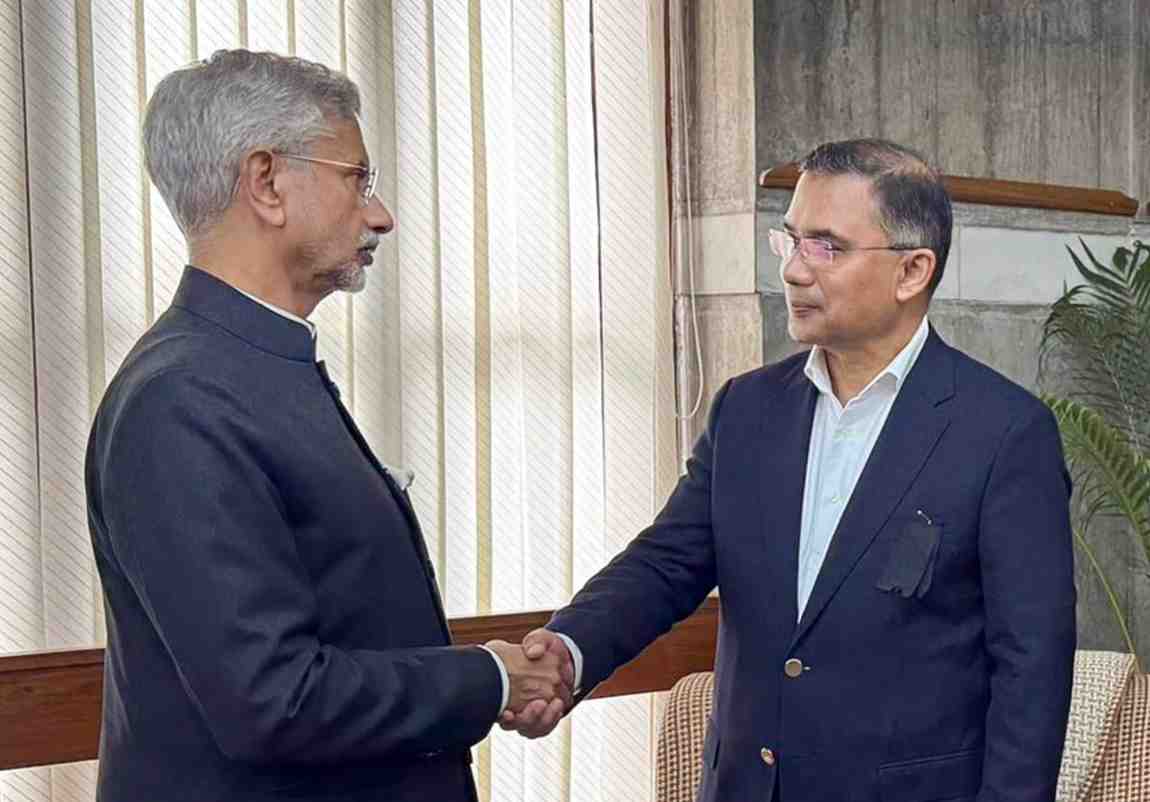

Dhaka outreach? Foreign minister S Jaishankar was right to attend Khaleda Zia’s funeral in Dhaka

Dhaka outreach? Foreign minister S Jaishankar was right to attend Khaleda Zia’s funeral in Dhaka

Some in Pakistan may believe that the first sign of these improving regional dynamics came much earlier when the Monsoon Revolution in Bangladesh in July 2024 swept away the Awami League govt. Pakistan-Bangladesh relations had stagnated at a very low level throughout the long duration of Sheikh Hasina’s second tenure as prime minister from 2009 to 2024, and this change in Dhaka was seen as an opportunity to reset the relationship.

After more than a decade, Pakistan’s foreign minister (who is also deputy prime minister) visited Bangladesh in 2025. There have been other ministerial and high-level military contacts. There are positive statements from both sides on trade and economic cooperation, as also some expectations of the resumption of direct flights. For former PM Begum Khaleda Zia’s funeral, there was high-level participation from Pakistan.

Taken together, this may amount to no more than a modest revival of a long-moribund relationship. Nevertheless, from a Pakistani perspective, this new civility —certainly there is more than civility here — marks a significant breakthrough given the deep divides that existed over 1971 and its multiple legacies.

For India, however, the fear that Bangladesh could be visibly reverting to something akin to East Pakistan once again forms the subtext of many conversations. In fact, the dramatic intensity of events that forced Sheikh Hasina into exile in 2024 recalled the events of August 1975 and the upheaval that followed Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s assassination.

Sheikh Hasina’s long tenure as PM had come to represent all the promise and potential of 1971. The upsides and gains were directly visible in relations with India in terms of trade and investment, infrastructure and connectivity. Bangladesh reverting to an East Pakistan-type of neighbour is, therefore, a nightmarish scenario. The Radcliffe Line on the East is immeasurably more complex than the fenced and tightly regulated international border or LoC on the West. The security ramifications of an adversarial relationship with Bangladesh are uniformly bleak.

The accumulated wisdom about Bangladesh points to a country with a deep divide best summarised as the spirit of 1947 in collision with the spirit of 1971. Through at least some strands of its politics, we can see the forces of religious and linguistic nationalism battling it out. There is merit in viewing both as indigenous impulses rather than falling for the temptation of seeing them as simply proxies for Pakistan and India.

The past few days have presented a deeply worrying picture. Acerbic statements by both govts have coincided with the corrosive impact on public opinion in India of attacks on minorities in Bangladesh. Sheikh Hasina’s asylum in India will remain a constant point of friction. The exclusion of the Awami League from the election and the political marginalisation of pro-India elements will continue to be a source of deep frustration for us. The growing power of Islamist forces, including the Jamaat-e-Islami, will inevitably raise the spectre of Pakistan. Our own emergent electoral landscape further compounds these complexities.

History may not offer neat lessons, but it does contain warnings. Pakistan broke up because the spectre of India in East Pakistan blinded its leadership into committing error after error. There are numerous other examples of strategic errors born of seeing a situation in Manichean or black-and-white terms. Given Bangladesh’s turbulence, we should learn to live in a grey world for some time. There is also a lesson from the ‘measurement problem’ of quantum mechanics: You will find what you look for. If we remain too focused on the shadow of Pakistan, it will pop up everywhere and end up blinding us. It’s far better to concentrate on our strengths and be patient. External affairs minister S Jaishankar’s visit to attend Khaleda Zia’s funeral was a good step. We should look for more such opportunities.

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE