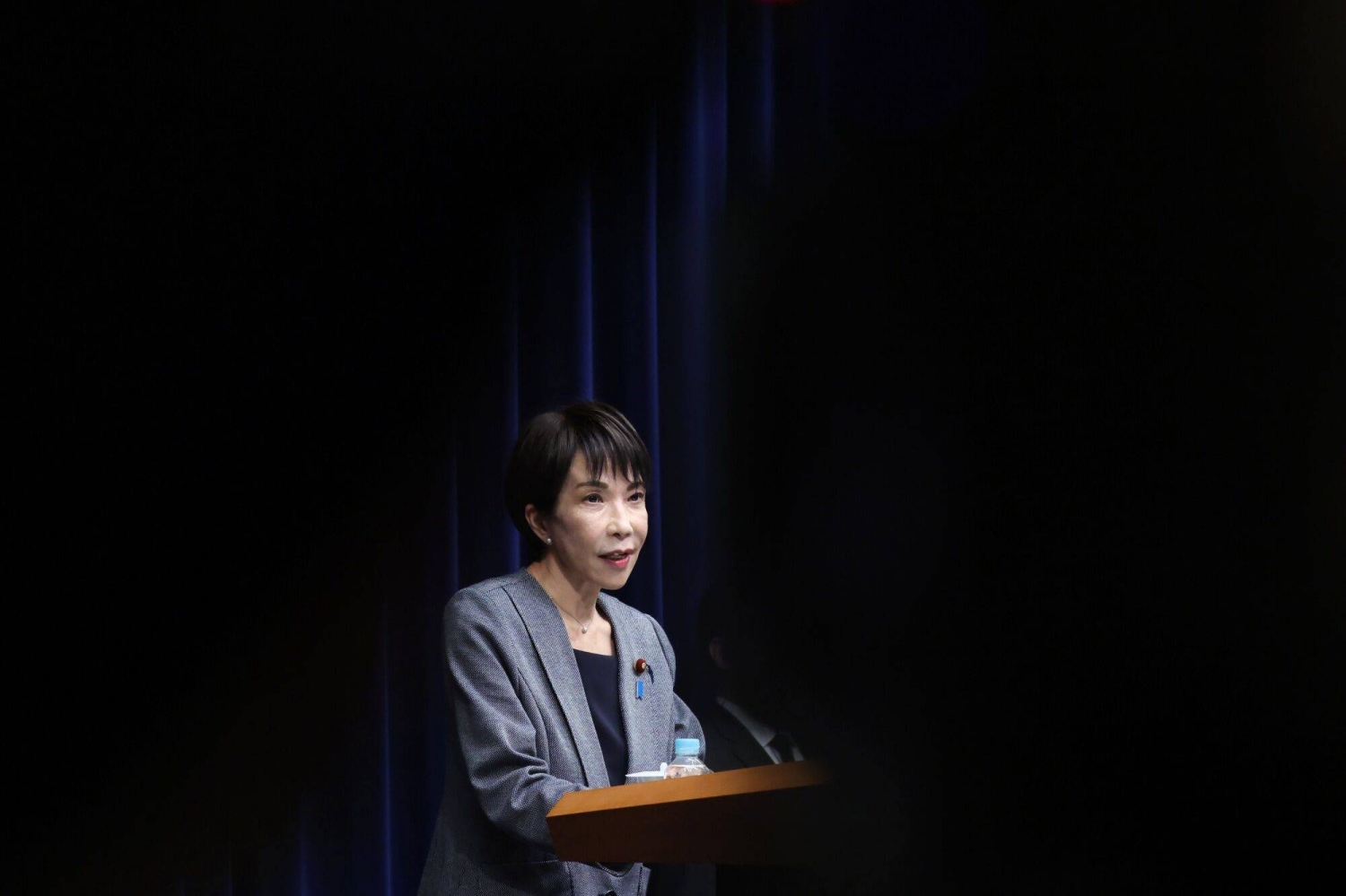

As she settles into the nation’s top office, Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s energy policy is coming into focus.

Conventional nuclear power and the pursuit of futuristic technologies like nuclear fusion are being prioritized, while renewable energy, especially megasolar, is getting less attention.

Over her short two months in office, Takaichi has emphasized the restart of aging nuclear reactors and developing futuristic — but not yet commercially viable — technologies like nuclear fusion. She has also given considerably less attention to renewables, with the exception of geothermal, all with the goal of making Japan 100% energy self-sufficient.

Takaichi’s bid to resurrect nuclear power comes despite significant renewable energy growth in recent years, as Japan pursues its goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry data show that renewable energy provided 23% of Japan’s electricity generation in fiscal 2024, while nuclear’s share was 9.4%. Thermal power (including oil, LNG and coal but excluding biomass), however, still accounted for the largest share at 67.5%, raising significant questions about whether the goal of self-sufficiency is achievable.

Last February, Japan’s latest Strategic Energy Plan included a goal to increase the share of renewable energy in power generation from approximately 20% to between 40% and 50% by the 2040 fiscal year.

But that plan was approved during the administration of Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba and it’s clear that Takaichi intends to take Japan in a slightly different direction.

Here is where things stand at the end of 2025 with the Takaichi government’s views on key energy sources.

Nuclear power

Takaichi, long one of Japan’s strongest advocates for nuclear power, says the controversial energy source is needed to deal with projected increases in electricity consumption, especially by energy-hungry data centers. But so far she has provided few details as to how much it will cost to restart many of the country’s still-dormant nuclear reactors.

Nationwide, Japan has 60 reactors. Of these, 24 are being decommissioned, a process that will take decades. The two dozen being scrapped include 10 in Fukushima Prefecture, where the March 11, 2011, quake and tsunami caused a triple meltdown at Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings’ (Tepco) Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

Of the remainder, 14 had been restarted as of December. Another four have received permission to restart after beefing up plant safety, while eight are currently undergoing safety inspections after applying for a restart.

Ten reactors did not apply for restart approval and it’s unclear if they ever will.

Already during Takaichi’s tenure, the governor of Hokkaido approved the restart of a reactor at the Tomari nuclear plant in Hokkaido, operated by Hokkaido Electric Power, while the Niigata governor OK’d a restart of Tepco’s Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant, marking the first time a Tepco plant has been approved to go back online since the Fukushima disaster.

In fiscal 2023, Hokkaido received around 43% of its total electricity from renewables. Hokkaido Gov. Naomichi Suzuki gave his OK for restarting the Tomari No. 3 reactor — idled since 2012 — in the hope that it would bring down electricity bills.

“Electricity rates in Hokkaido are among the highest in the country. Hokkaido Electric has indicated its intention to reduce rates after the Tomari No. 3 restart,” Suzuki told reporters on Dec. 15.

That same day, Suzuki presented the central government with a list of requests in exchange green-lighting the restart. These included assistance for developing Hokkaido`s power grids and communication networks and efforts aimed at local economic revitalization of areas surrounding the Tomari plant.

In Niigata, the impending restart of the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant, which may provide up to 2% percent of power in the Tokyo area, could also come with similar local conditions about central government money to help with regional revitalization, further adding to the price tag for the Takaichi government’s push for nuclear power. Especially, said Niigata Gov. Hideyo Hanazumi, given ongoing local opposition due to safety concerns and questions about the necessity of nuclear power.

“Many residents in the prefecture still feel uneasy about the restart, and many harbor distrust toward the operator,” the governor told Takaichi on Dec. 23, when he conveyed his decision to allow the restart.

But even as Takaichi is pushing the restart of the aging conventional reactors, she has kept one eye on nuclear fusion and the enormous potential the energy source offers as a safer alternative to nuclear fission.

Unlike nuclear fission, which is the process that powers conventional nuclear plants, fusion sees two atoms slam together to form a heavier atom, the same process that powers the sun, creating huge amounts of energy without producing radioactive waste.

The potential for nuclear fusion reactors has long been known. But the extremely high temperatures needed to sustain a fusion reaction mean commercial viability is still far from reality.

Last year, a project called FAST (Fusion by Advanced Superconducting Tokamak), which aims to demonstrate fusion power generation in Japan sometime in the 2030s announced they had completed a conceptual design for a device.

But much about the project has yet to be decided, including where in Japan a nuclear fusion reactor would be located, when it might start generating electricity and whether it can be cost-competitive. Despite those major question marks, Takaichi sees the technology as a key part of her current economic security strategy to reduce reliance on energy imports.

Finally, there is the issue of what Takaichi intends to do about reprocessing spent nuclear fuel at a plant in Rokkasho, Aomori Prefecture. Last year, Japan Nuclear Fuels Ltd. (JNFL), the plant’s operator, announced that the start of operations had been pushed back to 2027 — the 27th time the facility has been delayed due to technical problems.

Tadahiro Katsuta, a Meiji University professor and nuclear policy expert who served on the independent Nuclear Regulation Authority’s safety regulation review team, is skeptical that the Rokkasho reprocessing plant will ever work.

“Even if it does start operating, I believe there is a high possibility it will shut down immediately due to operational issues,” he said. “JNFL, which has no experience in reprocessing, is being monitored by the NRA, which also has no experience with reprocessing. It will be difficult for a plant with such complex circumstances to continue operating smoothly.

Geothermal

When Takaichi signed a coalition agreement in October with the Japan Innovation Party, also known as Nippon Ishin no Kai, one of the promises she made was to explore the potential of geothermal energy sources.

Geothermal has long been seen by proponents as a missed opportunity for Japan.

The Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMAC) estimates total geothermal potential at around 23 gigawatts, the third largest in the world after the United States and Indonesia. However, Japan ranks 10th worldwide in terms of installed capacity. Geothermal provided only 0.3% of Japan’s total electricity in 2023 and that figure is expected to rise to only 1% by 2030, and to 1% to 2% by 2040.

On Oct. 20, the same day Takaichi met with the JIP’s Hirofumi Yoshimura to sign the coalition agreement, LDP and opposition party members promoting geothermal attended a JOGMAC-sponsored seminar in Iwate Prefecture.

“In the government’s revised basic energy plan earlier this year, geothermal energy is prioritized. This has created an environment in which geothermal energy — which previously struggled to make progress — can move forward in collaboration with the hot spring industry and close dialogue with those who are protecting the environment,” said former Environment Minister Goshi Hosono, an LDP lawmaker who leads a parliamentary group pushing for further development of geothermal.

“Geothermal power will also be a major method of revitalizing local areas, creating local jobs and production,” added Kenta Izumi, a senior leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party and member of the geothermal group.

Given its wide-ranging political support, additional funding for geothermal-related projects is likely to be a part of the Takaichi administration’s discussions once the 2026 session of parliament begins.

Solar and wind

The prime minister made headlines with her opposition to megasolar project development in the Hokkaido’s Kushiro Wetlands area, and her government is proposing that new operators be excluded from government subsidy programs beginning in fiscal 2027.

Other large-scale megasolar projects have also been targeted by Takaichi’s administration, especially those that threaten the environment. On Dec. 23, the government announced that it was tightening environmental protection rules for new megasolar developments.

But Takaichi does not oppose solar energy if it’s developed in Japan. During parliamentary questioning last month by right-wing nationalist Sanseito leader Sohei Kamiya about Japan’s energy policies, she emphasized that the industry should not look to other countries for solar panel technology.

“Rather than simply installing imported solar panels, we should focus on promoting perovskite solar cells invented in Japan,” she said.

Perovskite solar cells are one-hundredth the thickness and one-tenth the weight of conventional silicon-based solar panels. They are also resistant to distortion and can be installed in a broader range of areas than conventional panels. The New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization has set a goal of power generation costs of ¥14 per kilowatt hour, about the same as conventional solar cells, by 2030.

Takaichi has said little about either on or offshore wind power, another major renewable energy resource, since taking office.

Ishiba’s Strategic Energy Plan had positioned offshore wind as the centerpiece of future expansion.

“Japan added more offshore wind capacity in 2024 than ever before, albeit from a modest base, reaching 253.4 megawatts (MW) of operational capacity,” according to a report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “Meanwhile, onshore wind capacity stood at 5,330 MW at the end of that year.”

Natural gas

Liquefied natural gas accounted for nearly 30% of Japan’s electricity in fiscal 2024. Under Takaichi, efforts are being made to increase Japanese investment in the U.S., which accounted for 8.7% of Japan’s 2024 LNG imports, after Australia, Malaysia and Russia.

But some projects are still on the drawing board. At her October meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump, the U.S. and Japan announced that Tokyo Gas and JERA, a 50-50 joint venture of Tepco and Chubu Electric Power, signed letters of intent for LNG from a yet-to-be-built Alaska LNG pipeline.

At the same time, the Takaichi administration convinced Trump to grant Japan an exemption from sanctions on Russia’s Sakhalin-2 oil and gas project that brings Russian LNG to Japan to the tune of 10% of total LNG imports. Tokyo Gas and JERA, as well as Kyushu Electric Power, are the major customers for Russian LNG.