Contents

Why the United States Needs a Competitive Space Industry 4

The Space Industry’s Greatest Regulatory Challenges 6

Securing Spectrum for Launch Operations 11

Aging Spaceports and Operational Bottlenecks 12

Today, the United States faces fierce competition for a fixed market share of globally traded advanced industries, including space industries. This competition is win-lose, meaning any market share that another country gains is lost from the U.S. economy.[1] For example, if another country develops better rocket launch capabilities than that of the United States, then the U.S. share of the global launch industry will fall.

American market share is important because space is a dual-use industry, meaning that advancing America’s space capabilities has both economic and national security benefits.[2] Many commercial space operators use federal infrastructure for launches, and the military often uses commercial launch vehicles and payloads for national security missions. Space-based defense capabilities are important as adversary nations develop offensive space technologies.[3] Further developing the commercial space industry is critical for protecting the homeland.

A robust space industry will enhance American economic welfare and defense capabilities by creating new industries, spurring economic growth, supporting national security missions, and enabling innovation, all of which lead to key developments in related industries such as telecommunications, agriculture, precision navigation, and healthcare. As such, the United States should make competing in the space economy a policy priority. The United States is currently the global leader in space, but regulatory bottlenecks, insufficient resources, and aging infrastructure risk ceding the advantage to China.

Regulatory modernization can help unleash America’s innovative potential, but without more comprehensive reform, the United States risks falling behind in the global race to lead in space innovation.

President Trump’s executive order (EO) 14335 on Enabling Competition In The Commercial Space Industry aims to modernize key space policy regulations, including licensing for launch and reentry vehicles, the development of spaceports, and environmental reviews for space operations and infrastructure.[4] The EO represents an important step toward remaining competitive by recognizing the barriers to progress that space companies face in the United States and working to remove them.

However, significant challenges remain. This report outlines why U.S. competitiveness in space is important, discusses the state of the U.S. space industry, highlights the effective reforms in the EO, and suggests further steps lawmakers should take to support U.S. competitiveness in space. Regulatory modernization can help unleash America’s innovative potential, but without more comprehensive reform, the United States risks falling behind in the global fight to lead in space innovation.

A competitive space industry will provide far-reaching benefits that go beyond space capabilities.

Space Industry Contributions to the U.S. Economy

The most recent available data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) shows that in FY 2023, the total U.S. space economy generated $241 billion in gross domestic product (GDP) and supported 373,000 private sector jobs.[5] The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) generated more than $75 billion in GDP and supported more than 304,000 jobs.[6] The space economy accounted for 0.5 percent of total U.S. GDP that year, and real GDP attributable to the space economy increased by 0.6 percent, representing the second straight year of positive real growth.[7]

The economic benefits of a strong space economy will continue to grow, and advanced space capabilities will spur growth in other key industries too.

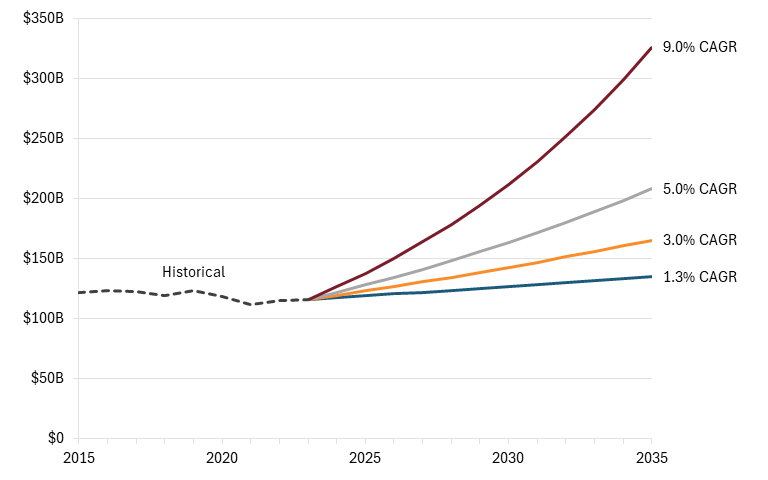

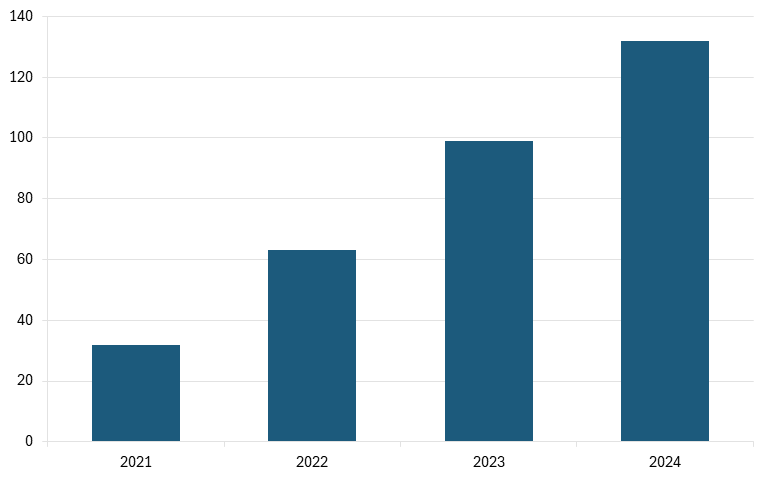

BEA data from 2021–2023 can help predict gains in the U.S. space economy for 2026 and beyond. Figure 1 presents BEA’s latest set of satellite account estimates. These statistics introduce new data for 2023, and revised statistics for 2012–2022, that reflects updates from BEA’s 2023 comprehensive update of its National Economic Accounts, as well as BEA’s 2024 annual update of its National Economic Accounts.[8]

Figure 1: Potential growth of the U.S. space economy (real value added, 2017 dollars)[9]

Analysis from the World Economic Forum and McKinsey & Company predicts that the global space economy will grow 9 percent annually. Applying that same growth rate for the United States predicts that the U.S. space economy will reach $326 million by 2035.[10] The economic benefits of a strong space economy will continue to grow, and advanced space capabilities will spur growth in other key industries too.

Space Capabilities Lead to Innovation and Growth in Other Industries

The evolution of satellite technology enables the advancement of related industries such as communications, agriculture, disaster prevention, navigation, and healthcare.

Communications

Communications satellites have become a legitimate competitor in the consumer broadband market, making connectivity more accessible in areas that were previously unreachable with terrestrial technologies, including many developing countries.[11] This advancement is critical, as the United States and China compete to develop low-earth orbit satellite constellations that will provide connectivity for people around the world.[12] The developing world is a large market in which the United States should prioritize outcompeting China for market share as it joins the connected world. Communications satellites are also driving advancements across other communications technologies through services such as direct-to-device connectivity, in-flight Wi-Fi, and backups to terrestrial networks in the event of natural disasters.[13] Certain states and the federal government leverage satellite broadband for programs aiming to close the digital divide because of these advancements.[14]

Precision Agriculture

Satellite imaging from low-earth orbit, remote sensing, and navigation systems improves precision agriculture. The United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs says that satellite imaging enhances agricultural development and food security by providing farmers with critical information, such as quickly pinpointing low productivity zones across massive areas.[15] This data saves time and manual labor, which allows farmers to focus on solving problems instead of merely identifying them.

A robust space industry will enhance American economic welfare and defense capabilities by creating jobs, growing GDP, advancing national security missions, and enabling innovation.

Disaster Prevention and Response

Satellites also enable early detection of natural disasters and aid in quick, effective response.[16] Satellite data “on ground moisture, surface temperature, and atmospheric pressure” can also help predict floods and landslides.[17] During an emergency, satellites can rapidly collect and disseminate key information to first responders, find evacuation routes, and track the progression of floods and wildfires.[18] Satellite imaging can assess damage and aid reconstruction after a natural disaster using pictures taken before such an event.[19]

Positioning, Navigation, and Timing

Positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) capabilities, of which the Global Positioning System (GPS) is the most widely used, are critical for commercial operations across numerous sectors, including many of consumers’ favorite applications. Rideshare apps, dating apps, online gaming, and e-commerce platforms all rely on GPS to function.[20] GPS is also critical for industries such as maritime navigation, supply chain management, and the financial sector.[21] A 2019 study from RTI, on behalf of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, shows that GPS has produced $1.4 trillion in U.S. economic benefits since its establishment 1980.[22]

Healthcare Science on the International Space Station

Science on the International Space Station (ISS) has led to breakthroughs in drug development and disease prevention. Protein crystal growth experiments on the ISS for creating new disease-fighting drugs have yielded positive results, especially one experiment on an incurable genetic disorder called Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.[23] Other ISS research on diseases, including cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and asthma, provides critical insights for understanding how to fight them.[24]

These experiments are more effective on the ISS because the lack of gravitational influence allows researchers to study disease proteins and drug crystals with greater precision and gain a clearer understanding of their properties and responses to treatment.[25] Science aboard the ISS is essential for a better understanding of the biology of humans back on Earth.

Space Capabilities Are Dual Use

Defense agencies, such as Space Force, work with private space operators to enhance national security capabilities. Space Force released its Commercial Space Strategy last year, which outlines how the agency will “leverage the commercial sector’s innovative capabilities, scalable production, and rapid technology refresh rates to enhance the resilience of national security space architectures.”[26] Private space companies contribute to military space capabilities by developing rockets and specialized satellites that enable offensive and defensive operations from orbit.[27] In turn, private space companies often use federal launch ranges for conducting commercial operations.

The military benefits from a strong space industry, which, alongside the economic benefits, is why the United States must dominate the global space economy.

In addition to cooperation and shared resources, many of the aforementioned space capabilities are dual use. Communications satellites are critical for military operations and coordination, especially in remote areas such as the middle of the ocean.[28] Satellite imaging and PNT are essential tools for numerous battlefield and intelligence operations.[29] The military benefits from a strong space industry, which, alongside the economic benefits, is why the United States must dominate the global space economy.

Despite the immense potential benefits of U.S. space dominance, an overburdensome regulatory landscape prevents the United States from reaching the full economic and national security potential of a robust space industry. Commercial space operators face multiple layers of regulatory reviews from numerous different agencies. These cumbersome and often duplicative efforts slow the pace of innovation, threatening U.S. leadership in space.

Permitting for Launch and Reentry Vehicles

A core part of U.S. space regulation is licensing for launch and reentry vehicles. These vehicles, depending on type, are designed to reach outer space, deploy satellites, carry cargo, and transport humans and then reenter the atmosphere for recovery and use in additional launches. Companies must obtain a license from the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) Office of Commercial Space Transportation (AST) to operate a launch and reentry vehicle.[30]

Launch operators must secure authorization for a vehicle itself, the payload it intends to carry, and the associated mission support operations, communications during launch, and emergency preparedness if something goes awry. Each of these license components involves oversight, potentially from different agencies, including the Department of Transportation (DOT) via the FAA, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which issues licenses for launch communications spectrum, the Department of War (DOW), the Department of State (DOS), the Department of Commerce (DOC), and NASA.

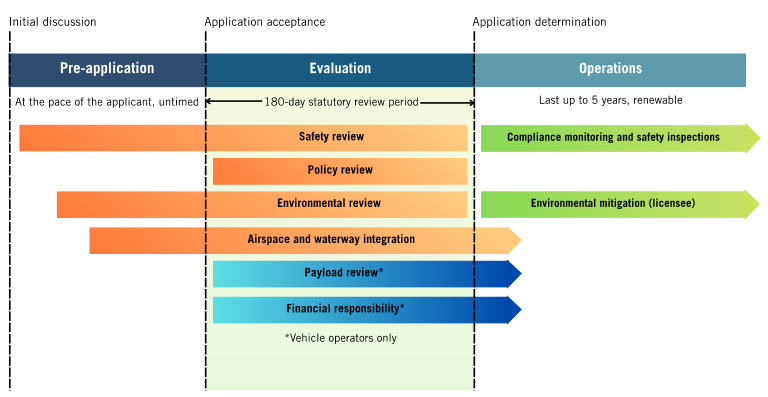

The Vehicle Licensing Process

AST oversees the permit review process, which begins when a prospective applicant notifies the agency that they would like to initiate the pre-application process.[31] AST and the applicant hold initial discussions on the applicant’s Concept of Operations (CONOP), which determines the regulatory review path the application will take, including the other reviewing agencies. Once the path is set, applicants move into the pre-application consultation period, when they work with a team from AST to create and refine their license documents.

Applicants often spend months going back and forth with AST before they can apply for a license.

The pre-application consultation is one of the biggest pain points for applicants.[32] While the FAA must complete its formal review within 180 days, that shot clock does not include the initial discussions and consultation period. Applicants often spend months going back and forth with AST before they can apply for a license.

The official application review begins at completion of all necessary application components.[33] It contains five primary components, most of which require additional review from other agencies:

1. Safety review. The FAA, alongside the FCC and DOW for certain launches, evaluates potential risks to public health and safety from the vehicle design and launch operations.[34] This review includes verifying that any debris from the launch will not harm people or property, listing any hazardous materials used in the propulsion system, and proving that there is no risk of collision with other orbital objects. Licensees must also provide a safety plan, including lines of communication between the vehicle and ground control, a hazard control strategy, and an abort system. Misaligned safety requirements between the FAA, DOW, and FCC (for launches involving communications satellites) may cause delays for launches at the federal ranges.

2. Policy review. The FAA consults with DOW and DOS to identify any implications for national security or foreign policy.[35]The FAA may flag an application if the vehicle design or associated launch operations pose security risks or are noncompliant with international obligations.

3. Payload review. The FAA reviews all commercial payloads. The FCC also evaluates payloads containing commercial communications satellites.[36] The FAA consults with DOW and DOS for payload reviews to assess security or foreign policy risks, as they do with policy reviews. Applicants must provide information for both the launch and reentry of payloads, including the payload operations, physical descriptions of payload equipment, the delivery point and lifespan of the payloads, a list of any hazardous materials and explosive risks, and the designated launch and reentry sites. NASA is responsible for government-owned payloads.

4. Financial responsibility requirements. Applicants are financially responsible for any damage to property or injury to persons that occur from launch and reentry operations.[37] The FAA requires operators to demonstrate sufficient liability insurance or financial reserves to cover maximum probable loss.[38]

5. Environmental review. The FAA must comply with federal environmental protection laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).[39] Applicants may need to provide an environmental assessment or an environmental impact statement showing compliance with the relevant environmental protection regulations.[40]

Figure 2: AST licensing process flow chart[41]

The Impact of Part 450

Until 2020, the launch and reentry vehicle licensing regime (see figure 2) was divided into four separate regulations based on vehicle type. That year, the FAA adopted 14 C.F.R. Part 450 (Part 450), which consolidates the rules into a single framework.[42] The new regulation, which aligns with the “Evaluation” phase in figure 2, is performance-based, meaning applicants demonstrate a Means of Compliance (MOC) “identified by the FAA, or propose unique means of compliance that meet the safety standards of the regulation.”[43]

The goal of Part 450 was to create greater regulatory accommodations for new inventions. In practice, however, the cost of flexibility is regulatory efficiency. Applicants and licensees are struggling with Part 450 requirements, not because their vehicles and operations have become less safe, but because, in an attempt to be less prescriptive, the new rules have become ambiguous and complicated to navigate.

Performance-based reviews are good in theory, and industry supports them. Allowing operators to invent new launch vehicles and launch methods and then prove that those inventions comply with federal regulations is a positive step toward fostering a more innovative space industry.

But Part 450 implementation has been an overcorrection to the point that every license is a bespoke project requiring intensive review. For example, the lack of established requirements leads to duplicative payload reviews, as the FAA often requests information that other agencies have already approved. Unclear requirements mean operators must include application components that are not actually relevant to a proposed launch. Applications are growing by hundreds of pages as a result, slowing down the review process. Plus, the line between a license modification and a continuing accuracy update is no longer clear, so operators often go through the long process of modifying a license for inconsequential changes.

The result of these implementation problems is that every application requires more extensive review by AST, leading to a drawn-out approval process.[44] In one instance, an operator had to wait three years for a launch license.[45] As of 2024, AST has only issued four Part 450 licenses, and two of those took longer than the 180-day shot clock.[46]

Space operators want Congress and the FAA to clarify the rules for Part 450 implementation and to provide AST with additional resources to streamline licensing.[47] AST’s primary approach to aiding applicants is through commercial space advisory circulars (ACs) and a list of previously accepted MOCs.[48] There are currently 28 ACs, of which 22 pertain to Part 450, including subjects such as “Tracking for Launch and Reentry Safety Analysis” and “Applying for FAA Determination of Policy or Payload Review.”[49] However, without a complete set of Part 450 ACs and clearer guidelines for proving novel methods of compliance, the shortcomings of Part 450 implementation will undermine the benefits of performance-based reviews.

Numerous licensees will become noncompliant without a deadline extension, which will halt commercial operations and cause major setbacks for American space innovation.

AST is also aiming to fix Part 450 through the Space Aerospace Rulemaking Committee (SpARC).[50] The SpARC’s goal is to bring together industry and government leaders to change Part 450 and to improve the licensing process. While the SpARC’s findings were originally planned for release in late summer 2025, none have been released as of this writing.

Yet another consequence of the issues with Part 450 is that many operators have yet to transition existing applications from the legacy rules to the new ones.[51] This is problematic because there is a looming deadline of March 10, 2026, for Part 450 compliance for all licensees.[52] This deadline does not provide enough time for all operators to transition existing licenses considering applicants’ current compliance difficulties. Numerous licensees will become noncompliant without a deadline extension, which will halt commercial operations and cause major setbacks for American space innovation.

What the EO Accomplishes

The EO correctly recognizes the need to reform launch and reentry licenses. It highlights the need for Part 450 exemptions for vehicles with a flight termination or automated safety systems, or those that hold a valid FAA airworthiness certificate.[53] These exemptions ensure that applicants are compliant with relevant safety requirements without needing a lengthy, cumbersome, back-and-forth process to do so. This emphasis on efficiency acknowledges that licensing delays pose a threat to American competitiveness.

What Policymakers Should Do

Despite these improvements, the most critical problems with the licensing framework remain. The White House should mandate that AST close the loophole that exempts the pre-application consultation period from the shot clock. The whole regulatory process should fall within the shot clock for the official review timeline to prevent unnecessary slowdowns.

AST must reform Part 450 rules to improve the licensing process. FAA safety and payload reviews should align with other agencies to ensure consistency and prevent duplication. AST should provide greater clarity on the fidelity of analysis requirements to avoid slowdowns from collecting data irrelevant to an application. AST should also adjust the threshold for license modifications to better account for continuing accuracy updates without requiring additional paperwork.

Lawmakers can unleash private innovation and strengthen U.S. leadership in space by tackling the critical roadblocks in the licensing process.

While the FAA claims that reviews will be faster once industry and AST staff become more familiar with the new rules, regulators must make more substantial changes to Part 450 implementation to reduce ambiguity.[54] This change means releasing a full set of Part 450 ACs and streamlining the process for licensing through preapproved means while allowing operators to propose and justify novel compliance if they so choose. AST should give space operators automatic approval for license components that use methods from an AC rather than treating the license like a novel project. The ideal system is regimented enough to make the application process clear and easy to navigate while also having a well-established performance-based review mechanism to allow for innovation.

There is also the problem of the March 2026 compliance deadline, which AST should extend to allow licensees more time to become Part 450 compliant. It would be catastrophic for U.S. space innovation if licensees, which already have complied with more stringent rules, must cease operations until they get FAA approval under the new system.

Targeted, comprehensive policy reform remains essential. Space is a strategic industry, meaning it is a highly technical, research-and-development-intensive, dual-use industry in which strong U.S. competitiveness is an economic and national security imperative.[55] As such, it would be detrimental to let regulatory burdens limit American progress. Lawmakers can unleash private innovation and strengthen U.S. leadership in space by tackling the critical roadblocks in the licensing process.

The FCC licenses spectrum that rockets use in communications systems that transmit data and telemetry to Earth and receive commands from ground control during launch. [56] The process for securing a license to use this spectrum previously was quite complex. Launch providers needed to obtain a temporary experimental license for each launch, thereby inundating the FCC’s licensing office and causing long wait times to secure approvals.

In 2024, Congress passed the Launch Communications Act (LCA), recognizing that the growing space industry needed access to additional spectrum.[57] The LCA instructs the FCC to work with the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) to “allocate on a secondary basis such frequencies for commercial space launches and commercial space reentries” in the 2025 to LCA bands of 2110 megahertz (MHz), 2200 to 2290 MHz, and 2360 to 2395 MHz.[58]

Good spectrum policy maximizes the productivity of spectrum, which means efficient management of interference is important.

As instructed, the FCC adopted Part 26 rules, which shifted the licensing model to one where providers get a nonexclusive, nationwide license for 10 years to access the LCA bands, and then coordinate licenses for specific launches via a third-party system.[59] While this new approach is an improvement over the old licensing methodology, there are also new implementation challenges.

The primary LCA bands are 2025 to 2110 MHz and 2200 to 2290 MHz, while the 2360 to 2395 MHz band (upper S-band) is reserved for spectrum deconfliction, meaning whenever there is an issue with using the other two bands.[60] But increasing launch cadences and more operators are causing congestion for getting approval to launch in the lower bands, creating the need to use the upper S-band more frequently. However, the upper S-band is already in use primarily by commercial and military flight test operators, and the Aerospace & Flight Test Radio Coordinating Council (AFTRCC) is the band coordinator.[61]

AFTRCC and SpaceX currently disagree on how to resolve geographic and temporal conflicts for the use of the spectrum. AFTRCC suggests that, under the new rules, areas around a launch site that require spectrum coordination (currently 320 km/200 miles) are too small, and that space operators should provide further necessary information in advance of each launch. The group has asked the FCC to expand the coordination zones and require space operators to submit notifications of planned launches at least 60 days in advance.[62]

SpaceX maintains that the requested changes would prevent the streamlining of launches, which the LCA aims to achieve. Expanding the coordination zones would require spectrum deconfliction with every potentially impacted flight test operator, likely grinding space launches to a halt given the extensive network of aerospace testing sites across the United States. Additionally, any coordination efforts 60 days before a launch would be meaningless. Space launch timing is fickle and changing for myriad reasons, including things as simple as bad weather. Therefore, the details for a specific launch are likely to change multiple times over 60 days. SpaceX submitted a letter to the FCC suggesting a 5- or 10-day window would be ideal because it’s close enough to the launch that the details shouldn’t change significantly, while allowing enough time for spectrum coordination.[63]

What Policy Makers Should Do

The key to good spectrum policy is maximizing the productivity of spectrum, which means efficient interference management is important.[64] However, in this case, the issue is not spectrum scarcity; it is ensuring that operators have enough high-quality, timely information about where other operators are in the band to prevent harmful interference. Maximizing upper S-band spectrum means finding the best spots in the band for operations to occur, as there should not be any great risk of harmful interference.

Maximizing productivity means allowing space launch operators to use the band as needed while also making sure that flight test operations can continue.

To coordinate effectively, AFTRCC must find ways to be more flexible and agile in its coordination of the upper S-band to accommodate space launch needs. The onus should be on AFTRCC to coordinate around test flight operations, as aerospace operations are easier to coordinate than space launches. Rocket launches only take a few minutes, and, given that there have been no instances of harmful interference from space launches in the upper S-band to date, maximizing productivity means allowing space launch operators to use the band as needed while also making sure that flight test operations can continue.

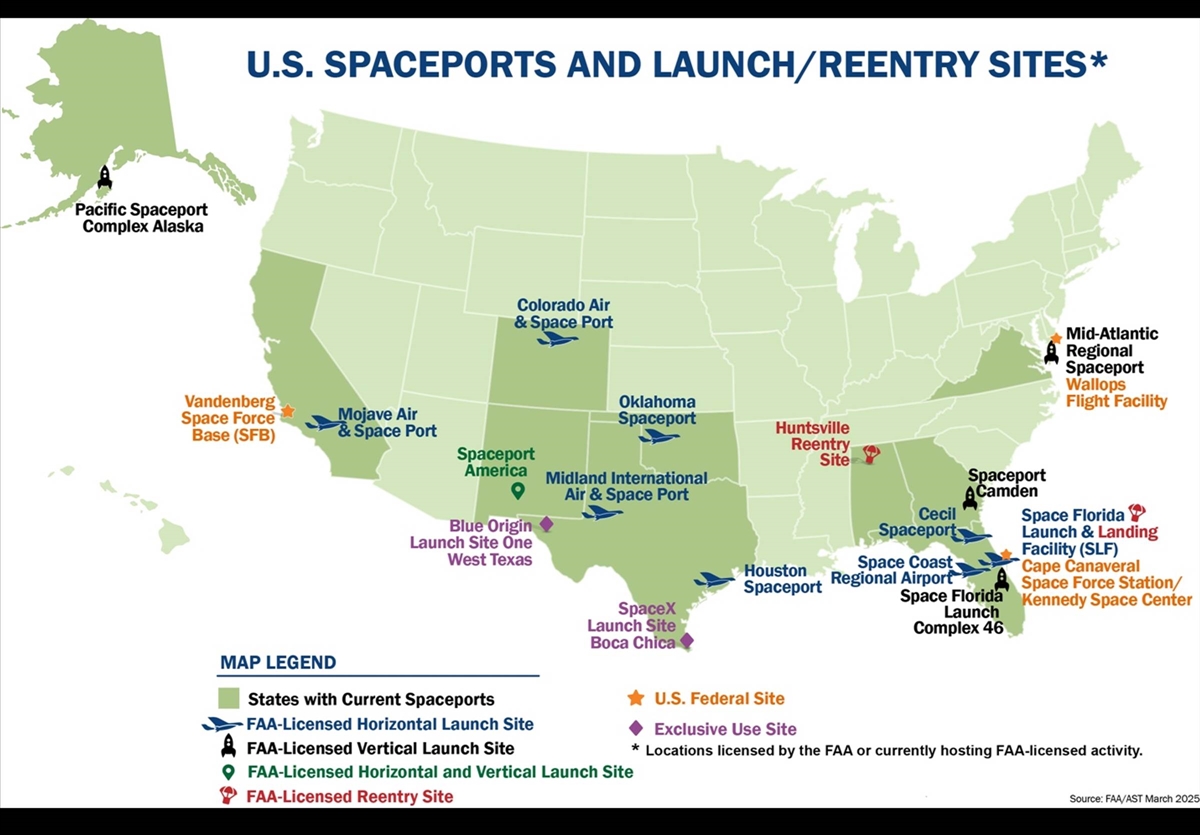

The United States hosts 16 launch sites, 2 reentry sites, and 3 federal launch ranges.[65] The three federal ranges include the Mid-Atlantic range in Virginia, which hosts the NASA Wallops Flight Facility; the Eastern range in Florida, which hosts the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and NASA’s Kennedy Space Center; and the Western range in California, which hosts the Vandenberg Space Force base. All three ranges support commercial and government launches, and the Eastern and Western ranges are the busiest spaceports in the country.[66] Beyond the federal ranges, there are 12 privately-owned FAA-licensed commercial spaceports and 2 exclusive-use facilities, one owned by SpaceX and the other by Blue Origin.

Figure 3: FAA/AST map of U.S. spaceports, March 2025[67]

Coordinating launch schedules involves many parties, leading to strained operational capacity at federal ranges and bottlenecks that limit the productive use of spaceports.

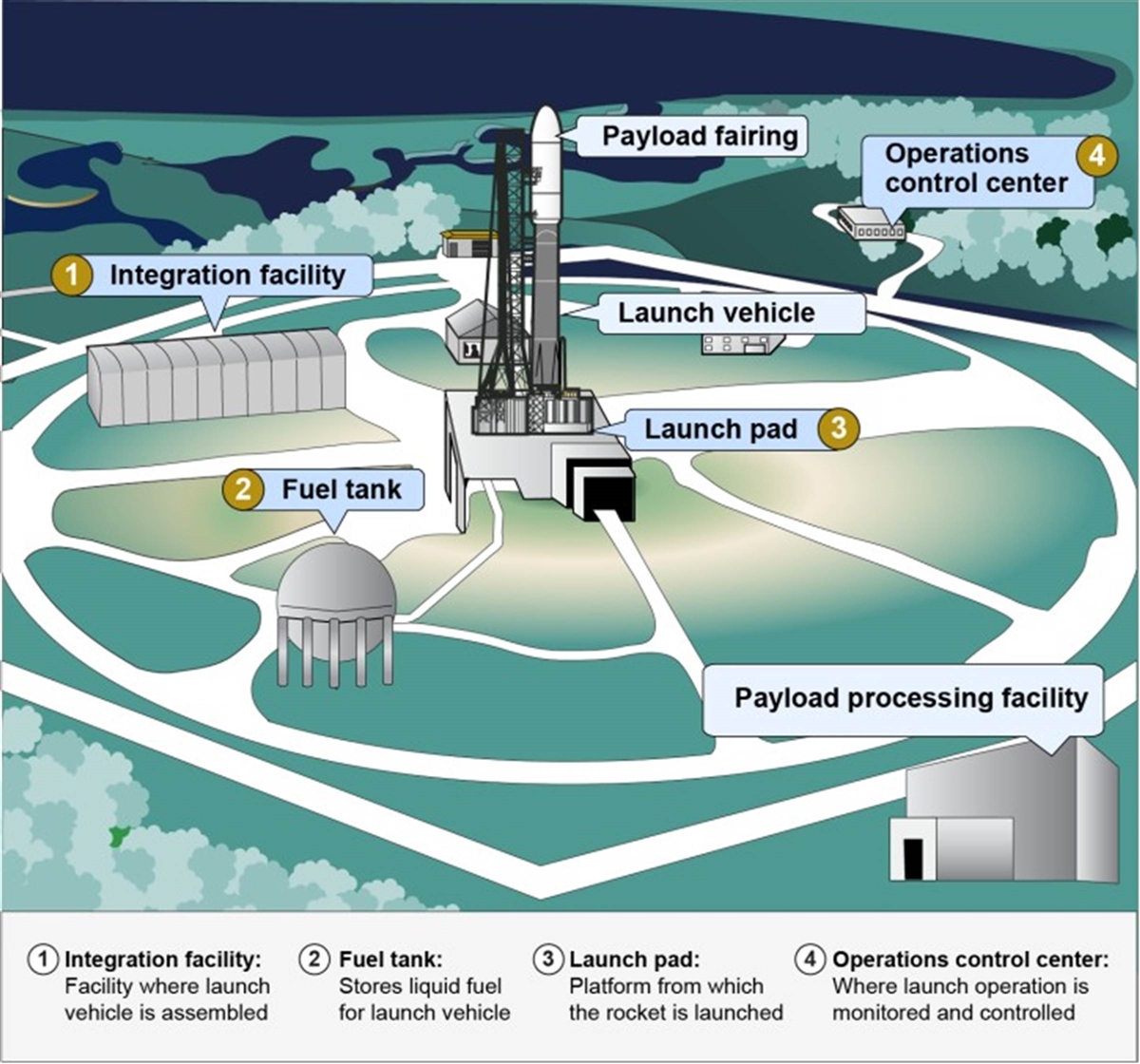

Each launch site contains multiple complexes with launch pads, fueling stations, integration facilities for rocket assembly, control centers for monitoring operations, and payload processing facilities for preparing satellites for flight.[68] The specific infrastructure components vary widely across spaceports, with some capable of handling superheavy-lift vehicles and others only able to handle smaller rockets. Owning and operating a spaceport also requires obtaining an FAA license.

Figure 4: Government Accountability Office presentation of a launch site[69]

Virtually all aspects of Cold War spaceports need improvement.

Increasing Use of Federal Ranges Is Causing Operational Bottlenecks

The scale of U.S. launches has grown exponentially in recent years, with larger rockets, more explosive rocket fuel, and an increased launch cadence. At the federal ranges, launch coordination involves launch providers, satellite operators, federal agencies, and the military. Coordinating launch schedules involves many parties, leading to strained operational capacity at federal ranges and bottlenecks that limit the productive use of spaceports.

Figure 5: Launches from U.S. federal ranges[70]

Part of this problem is a lack of geographic diversity of spaceports. The federal ranges in California and Florida are the optimal launch points because of the specific orbits that commercial and military operators want to reach. But this fact means that federal ranges are in high demand and, without more spaceports in other locations, bottlenecks could become much worse.

Another scheduling conflict at the ranges comes from nonlaunch activities. Many different military activities take place at these ranges, and in some instances, the range managers provide insufficient clarity on how they resolve scheduling conflicts, and will suspend launches without providing a clear explanation as to what happened.

The primary barriers to upgrading and expanding spaceports are funding for infrastructure and personnel.

Two reports provided to FAA in recent years highlight the need to better utilize spaceports. In 2020, a group called the Global Spaceport Alliance prepared a report for AST that outlines a national spaceport development plan.[71] Later that same year, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report encouraging the FAA to “examine a range of potential options to support space transportation infrastructure.”[72]

In 2022, the FAA launched the National Spaceport Interagency Working Group (NSIWG), comprising the FAA, NASA, DOS, DOC, and DOD, to develop a National Spaceport Strategy “to leverage the full network of domestic spaceports to the benefit of the space transportation industry and the nation as a whole,” among other coordination and standardization efforts.[73] However, there is no strategy yet, and coordination issues at federal ranges persist.

A Lack of Funding Means Current Spaceports Cannot Support the Growing Industry

Virtually all aspects of Cold War spaceports need improvement. To enable more frequent launch cadences and superheavy-lift rockets, federal facilities need upgraded wastewater treatment facilities, better roads for transporting rockets to launch pads, and enhanced payload processing centers.[74] Additionally, moving command centers to a safe distance away from the launch pads is necessary with the increased explosiveness of new liquid oxygen and liquid methane-based fuels.[75]

The primary barriers to upgrading and expanding spaceports are funding for infrastructure and personnel. Space Force plans to spend $1.4 billion from 2024 through 2028 as part of its Spaceports of the Future project, but it will not be enough to keep pace with commercial space innovation and launch needs.[76] Space Force does collect fees from commercial operators that use federal ranges, but GAO found in a recent audit that Space Force does not effectively document direct costs.[77] This lack of accounting means the government is likely undercharging for the use of its ranges, and better documentation of direct costs is necessary to raise the funds for the required infrastructure upgrades.

The dual-use nature of the federal ranges makes improving existing infrastructure and building new spaceports imperative for economic and national security.

Spaceports also lack sufficient numbers of qualified personnel, leading to costly bottlenecks. Space Force notes that there are staffing shortages in payload processing facilities at both the Eastern and Western ranges, leading to long wait times for commercial and government operators.[78] A lack of technical expertise also slows down such actions, as on-site safety reviews and grounds control operations. There needs to be a greater number of qualified staff members at the federal ranges to accommodate commercial and government missions now and in the future.

Infrastructure upgrades are critical not just for boosting the space industry but also for ensuring that the United States can keep pace with other countries’ space-based military capabilities.[79] The dual-use nature of the federal ranges makes improving existing infrastructure and building new spaceports imperative for economic and national security.

What the EO Accomplishes

The EO instructs agencies to align “review processes for spaceport development across agencies” and eliminate duplicative reviews.[80] This effort is good because it will allow relevant agencies to coordinate launches across all available spaceports to maximize launch capabilities. It also emphasizes the importance of finding ways to expedite the construction of new spaceports, which will help ease operational constraints.

What Policy Makers Should Do

Improving coordination at federal ranges is critical for commercial and military success. Congress should mandate that the NSIWG engage with private space operators more proactively to help create the National Spaceport Strategy. Additionally, military and federal operators should engage with private companies at the federal ranges more frequently to streamline day-to-day operational coordination.

Congress should help fund spaceport infrastructure improvements by authorizing federal agencies that manage the ranges to collect fees from commercial launch providers that reflect the total costs to the government. Those fees should pay for necessary infrastructure improvements, which would benefit all operators who use the federal ranges. Congress should also establish additional funding programs, such as Spaceports of the Future, to promote more rapid deployment and upgrades of this critical infrastructure.

Without more physical and human capital, spaceports will remain bottlenecked and inefficient, regardless of regulatory streamlining.

Finally, the president, through the Office of Personnel Management, should provide AST, Space Force, and NASA with the necessary resources and authority (including special hiring authority wherever necessary) to expand the number of personnel needed to efficiently process applications and conduct launch site operations. Without more physical and human capital, spaceports will remain bottlenecked and inefficient, regardless of regulatory streamlining.

Numerous environmental laws govern the space industry at multiple points in the licensing ecosystem, including for launch operations, spaceport development, and the use of federal ranges. The most cumbersome environmental law is NEPA, which multiple regulators implement when providing licenses for space operators.[81]

A Brief History of NEPA

NEPA has become the most significant hindrance to infrastructure development in the United States. If a federally licensed activity qualifies as a major federal action (MFA), it triggers a NEPA review.[82] NEPA itself is not a regulation; it’s a legal framework that licensing agencies use for preparing documents, including environmental assessments and environmental impact statements, showing that a licensed activity is compliant with environmental regulations such as the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, etc.

The main problem with NEPA is its use as a litigation tool.[83] The combination of an EO by President Carter in 1977, which gave the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) binding authority over regulatory agencies, with the 1980 Equal Access to Justice Act making it incredibly easy to sue federal agencies for suspected NEPA violations, and plaintiffs not having to pay the government back for legal fees if they lose the suit has resulted in an incredibly high number of NEPA lawsuits in which the licensing agency almost always wins, but the legal process massively delays the licensed.[84] Companies frequently abandon projects due to delays and skyrocketing legal costs.[85] The litigation incentives also drive agencies to take a long time to write litigation-proof rules that are likely far more prescriptive than necessary.

There has been some progress in reducing the negative impact of NEPA on infrastructure projects. The 2023 Fiscal Responsibility Act instructed agencies to adopt more categorical exclusions (CEs), streamline the review process, and provide further clarification on what qualifies as an MFA.[86] President Trump’s EO 14154 “Unleashing American Energy” instructs the CEQ to issue guidance on NEPA implementation and potentially rescind CEQ’s NEPA oversight.[87] CEQ then issued an interim final rulemaking confirming that it removed its regulatory authority and instructed agencies to create their own NEPA implementation methods.[88] Now agencies are establishing their own NEPA implementation approaches.[89] Congress is also pushing to improve the NEPA process through legislation such as the Standardizing Permitting and Expediting Economic Development (SPEED) Act.[90]

The FCC is reevaluating its NEPA implementation.[91] Part of the consideration is whether to create an overarching rule for CEs or create a list of individual CEs specific to particular MFAs.[92] The new NEPA rules exclude activities “entirely outside the jurisdiction of the United States” from qualifying as an MFA, and the FCC suggests that it will exclude space-based activities since any environmental effects will be outside the United States.[93]

The FAA has issued Order 1050.1G to establish its new NEPA implementation and does not currently have CEs for rocket launches.[94] The FAA also issues licenses for private spaceport development, including at the federal ranges. This means that if a private launch provider leases a launch pad and wants to do even simple developments, such as building a new fence, it may require a NEPA review. However, environmental assessments for both rockets and spaceports often result in findings of no significant impact (FONSIs), meaning there is no need for an environmental impact statement for that project.[95]

In addition to NEPA, the coastal locations of the federal ranges mean they are also under the jurisdiction of the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA).[96]A recent dispute between SpaceX and the California Coastal Commission (CCC) illustrates the complex regulatory dynamics spaceport operators and users face. The CCC appealed SpaceX’s plan to increase its launch cadence at the Vandenberg Space Force base from 36 to 100 launches per year, arguing that the company does not provide sufficient information showing that the increase won’t harm nearby coastal ecosystems, per CZMA requirements.[97]

Ensuring the correct implementation of laws is worthwhile, especially if improper enforcement is harming innovation.

Under the current process, the secretary of Commerce has the authority to resolve disputes, such as this one, that involve alleged violations of the CZMA.[98] Since the first coastal management program was approved, there have been 50 secretarial appeals, of which the secretary has overridden 17 and agreed with the appellant in the other 33.[99] In this case, however, the Air Force intervened instead, classifying some SpaceX launches as national security activities to exempt them from CZMA rules.[100]

What the EO Accomplishes

The EO instructs DOT to find CEs in NEPA for launch and reentry licenses, and all relevant agencies to do so for spaceport development.[101] This is good because it will make it easier to build new spaceports without getting caught up in unnecessary NEPA review. The EO also directs DOC, DOW, NASA, and DOT to evaluate CZMA compliance to ensure that states are not illegally blocking the development of spaceports. [102] Ensuring the correct implementation of laws is worthwhile, especially if improper enforcement is harming innovation.

What Policy Makers Should Do

Congress should also amend NEPA to reduce slowdowns to growth in the space industry.[103] Legislation should do the following:

▪ Expand the range of agency actions that are exempt from NEPA requirements.

▪ Reduce the need for new scientific and technical research for NEPA reviews.

▪ Limit the scope of review to environmental impacts that the proposed action causes directly.

▪ Limit the scenarios where agencies require extensions to develop environmental impact statements and environmental assessments.

▪ Require agencies to amend an overturned document within a set amount of time.

▪ Reduce the statute of limitations for the length of time someone can bring a NEPA suit against the licensing agency following a project’s approval.

▪ Set clear judicial guidelines for when a court should overturn an agency decision.

▪ Set timelines for judicial actions.

▪ Limit who can file a lawsuit to only parties directly impacted by licensed actions or those who participate in the public comment period for a licensed project.

Congress and federal agencies need to lead additional reforms that bolster the space industry.

As for the agencies licensing space activities, if an FAA license applicant conducts an environmental assessment that leads to a FONSI, the FAA should categorize the actions under the license as a CE for future applications. This approach will prevent duplicative review efforts on regular launch activities.

Additionally, the FCC should maintain its exclusion of space-based activities from the definition of an MFA under the new NEPA rules, since any environmental impacts will happen outside the jurisdiction of the United States.

The United States is in a critical moment for the future of the space economy. Commercial space capabilities are rapidly advancing around the world, and the United States finds itself in a stiff, competitive fight, especially with China. Comprehensive permitting reform and strategic industrial policies are necessary to win this fight. The Trump EO 14335 represents an important first step toward modernizing regulation. However, Congress and federal agencies need to lead additional reforms that bolster the space industry so the United States can maintain global space leadership and secure long-term economic, strategic, and national security benefits.

About the Author

Ellis Scherer is a policy analyst at ITIF covering broadband, spectrum, and space policy. He previously interned with NTIA and worked as a cybersecurity consultant. He holds a master’s degree in terrorism and homeland security policy from American University and a bachelor’s degree in politics and history from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

[7]. Georgi and Surfield, “New and Revised Statistics for the U.S. Space Economy, 2012-2023.”

[13]. “Satellite With Starlink,” T-Mobile, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.t-mobile.com/coverage/satellite-phone-service; “Starlink In-flight Wi-Fi,” Hawaiian Airlines, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www2.hawaiianairlines.com/our-services/in-flight-services/in-flight-wifi; Jericho Casper, “Satellite, Direct-to-Cell Connectivity a Lifeline During LA Wildfires,” Broadband Breakfast, January 13, 2025, https://broadbandbreakfast.com/satellite-direct-to-cell-connectivity-a-lifeline-during-la-wildfires/.

[18]. Hajkova, “Satellite Imagery for Emergency Management.”

[28]. Jared Keller, “The US Navy Is Going All In on Starlink,” Wired, September 30, 2024, https://www.wired.com/story/us-navy-starlink-sea2/; Sandra Erwin, “Starlink’s rise in the defense market forces industry to adapt,” Space News, April 8, 2025, https://spacenews.com/starlink-pushes-rivals-to-rethink-military-comms/.

[29]. Justin T. DeLeon and Frederick Elvington, “Leveraging Imagery Collection At The Tactical Level,” U.S. Army, March 7, 2025, https://mipb.ikn.army.mil/issues/jan-jun-2025/leveraging-imagery-collection/; “Military Communications & Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT),” Space Systems Command, accessed December 11, 20205, https://www.ssc.spaceforce.mil/Portals/3/Documents/Fact%20Sheets/SSC%20MilComm%20-%20PNT%20Fact_Sheet_symposium.pdf.

[41]. “Getting Started with Licensing,” FAA.

[49]. “Commercial Space Advisory Circulars,” FAA.

[53]. “Enabling Competition in the Commercial Space Industry,” White House.

[54]. Lindbergh, “Commercial Space Launch and Reentry Regulations: Overview and Select Issues.”

[62]. Kara R. Curtis, “Petition For Reconsideration Of The Aerospace and Flight Test Radio Coordinating Council, Inc. In the Matter of Allocation of Spectrum for Non-Federal Space Launch Operations (ET Docket No. 13-115),” AFTRCC, June 2, 2025, https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/document/10603700328965/1.

[67]. “U.S. Spaceports Map,” FAA.

[68]. “National Security Space Launch: Increased Commercial Use of Ranges Underscores Need for Improved Cost Recovery,” GAO.

[74]. “National Security Space Launch: Increased Commercial Use of Ranges Underscores Need for Improved Cost Recovery,” GAO.

[79]. Pollpeter, Barret, and Herlevi, 2025.

[80]. “Enabling Competition in the Commercial Space Industry,” White House.

[91]. “Notice of Proposed Rulemaking In the Matter of Modernizing the Commission’s National Environmental Policy Act Rules (WT Docket No. 25-217) and CTIA Petition for Rulemaking on the Commission’s National Environmental Policy Act Rules (RM-12003), FCC, August 14, 2025, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-25-47A1.pdf.

[100]. Kan, “California Again Rejects Starlink Launch Increase, But It Might Not Matter.”

[101]. “Enabling Competition in the Commercial Space Industry,” White House.