In 2026, the world is no longer defined only by military strength, economic size, or diplomatic reach, News.Az reports.

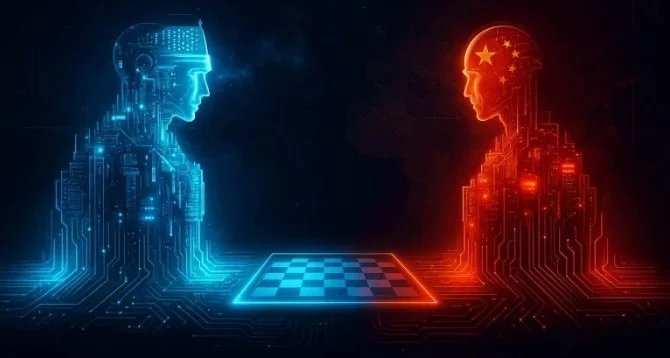

A new axis of competition has emerged — one shaped by artificial intelligence, the chips that power it, and the data pipelines that keep it alive. Governments speak less about arms races and more about algorithmic races. Power is increasingly measured not in barrels of oil or numbers of tanks, but in compute capacity, access to advanced semiconductors, and the ability to train the world’s most capable AI systems.

This escalation is now widely referred to as the “AI cold war.” It is not a conventional conflict and it is not fought directly on physical battlegrounds. Instead, it is unfolding inside data centers, semiconductor factories, research institutions, regulatory bodies, and cyberspace. Nations are investing heavily in AI as a strategic asset — one that underpins economic growth, surveillance, cyber-defense, social management, scientific research, and military planning. At the same time, fears of dependency, espionage, and digital coercion have accelerated the race.

Yet while the metaphor echoes the geopolitical tensions of the 20th century, the dynamics of 2026 are different. This competition is deeply intertwined with global supply chains, private technology giants, and the speed of innovation. The result is a fragile, interdependent environment in which the same technology that drives human progress can simultaneously amplify divisions and risk.

Chips as the new oil of the global system

At the heart of the AI cold war is hardware. No advanced AI system exists without high-performance chips capable of conducting enormous volumes of parallel calculations. These chips — whether GPUs, AI accelerators, or custom architectures — have become the most strategic commodity in the world.

Manufacturing them requires rare expertise, billion-dollar fabrication plants, and supply chains stretching across multiple continents. Nations that cannot produce or obtain such chips risk falling behind not only in AI, but also in automation, biotech research, climate modeling, cybersecurity, and defense.

By 2026, access to advanced chips is described as a national security priority in many capitals. Export controls, investment restrictions, and production incentives have reshaped the semiconductor market. Governments are not only seeking to secure chip supplies, but also to develop sovereign capability and protect intellectual property.

This has triggered a dual reality. On one hand, national resilience strategies have increased research spending and industrial investment. On the other, fragmentation threatens to slow global collaboration and deepen mistrust. Chip policy is no longer just about economics — it is a defining instrument of statecraft.

Algorithms as strategic infrastructure

If chips are the hardware foundation, algorithms are the operating layer of the new global order. AI models now underpin financial markets, logistics networks, scientific discovery, healthcare diagnostics, and intelligence analysis. Countries that lead in AI research and deployment have structural advantages across multiple domains.

What is new in 2026 is the level of autonomy granted to these systems. Governments and companies increasingly rely on AI not only to process information, but to recommend and sometimes execute decisions. Algorithms curate what citizens see, assess creditworthiness, optimize energy grids, and forecast social unrest. This scale of adoption raises profound questions about power, accountability, and control.

Nations are responding with regulation and governance frameworks. However, the pace of policymaking rarely matches the speed of innovation. The result is a constantly shifting landscape in which legal definitions, ethical boundaries, and security standards are still evolving. Meanwhile, competition ensures that no country wants to fall too far behind.

Data dominance and digital terrain

Every AI system is only as powerful as the data that trains it. Data has therefore become another currency of power. States with large populations, strong digital infrastructure, or major platform companies possess immense data reservoirs. Others seek to compensate through synthetic data, cross-border partnerships, or open-source ecosystems.

Control of data flows is now a central geopolitical issue. Governments are tightening rules around data storage, cross-border transfers, and access by foreign entities. National cybersecurity doctrines increasingly frame data networks as strategic assets comparable to critical infrastructure.

This trend carries both opportunity and risk. Better data governance can strengthen privacy, resilience, and trust. However, hardening digital borders may also fragment the internet, complicate research collaboration, and contribute to economic inefficiencies. The AI cold war is therefore not only about capability — it is about whose values shape the digital order.

Private industry at the center of geopolitical power

Unlike earlier global rivalries, the AI cold war is driven to a large extent by private companies. A small group of leading technology firms — cloud providers, chipmakers, model developers, and platform operators — possess resources that sometimes exceed those of nation-states.

These companies design the models, control the compute, manage the data centers, and operate the platforms that deploy AI at scale. Their strategic decisions influence economic competitiveness, information ecosystems, military innovation, and even democratic processes.

Governments are increasingly aware of this dynamic. Some collaborate with industry through formal partnerships, procurement programs, and strategic investment. Others expand regulatory oversight and nationalization strategies to retain leverage. Regardless of approach, the frontier of AI power in 2026 sits at the intersection of public policy and private capability.

Cyber power and algorithmic security

The AI cold war has also reshaped cybersecurity. Advanced AI tools enhance both offense and defense. Nations deploy machine-learning systems to detect threats, analyze network activity, and automate response. At the same time, attackers leverage AI to generate sophisticated campaigns, probe vulnerabilities, and mimic human behavior at scale.

Critical infrastructure — such as power grids, pipelines, satellites, and financial networks — is increasingly AI-enabled. That brings efficiency gains but also systemic risk. A failure, manipulation, or adversarial attack on an algorithmic system can cascade through entire societies.

As a result, algorithmic security has become a strategic discipline. It encompasses model robustness, data integrity, supply-chain assurance, and resilience planning. The line between traditional cybersecurity and AI governance continues to blur.

Military modernization and autonomous systems

Defense establishments across the world are integrating AI into intelligence analysis, logistics planning, surveillance systems, and autonomous platforms. The goal is not only battlefield advantage, but also speed — the ability to process and act on information faster than an adversary.

This creates ethical and strategic dilemmas. Autonomous systems challenge long-standing norms of command responsibility and proportionality. AI-driven escalation risks misinterpretation or unintended consequences. Military planners must balance innovation with caution, transparency, and international law.

By 2026, arms-control debate increasingly includes algorithmic behavior, training data bias, and the predictability of autonomous systems. The technology itself is advancing faster than the governance frameworks that might constrain it.

Regulation, trust, and global governance

The AI cold war is not solely about competition. It is also about governance — how the international community sets standards, codifies ethics, and manages shared risk. Multilateral institutions, regional unions, and coalitions of like-minded states are now deeply engaged in AI policy discussions.

Key questions dominate the debate. Who is accountable when AI fails? How do governments ensure transparency without exposing sensitive intellectual property? What legal rights should citizens hold over their digital identities? How can societies balance innovation with safety? And crucially, what constitutes responsible AI in the context of national security?

Different regions have adopted distinct models. Some prioritize civil-rights protections, others focus on industrial competitiveness or social management. These diverging philosophies shape the broader AI cold war dynamic — determining the rules under which algorithms are developed, deployed, and audited.

Economic implications and inequality of capability

AI is now a fundamental pillar of economic growth. The countries that deploy it most effectively may benefit from higher productivity, technological leadership, and innovation-driven industries. Those that lag risk structural disadvantage.

This uneven distribution of capability threatens to widen global inequality. Nations without access to advanced chips, capital investment, or research ecosystems may be limited to downstream usage rather than innovation leadership. That has knock-on effects for employment, education, and sovereignty.

In response, some governments are investing aggressively in digital infrastructure, STEM education, and technology ecosystems. Others pursue partnerships, sovereign technology funds, or participation in open-source communities. The global AI economy in 2026 reflects both intense competition and a shared recognition that the technology is now foundational.

Ethics, society, and the human dimension

Beyond strategy and economics, the AI cold war raises deeper societal questions. As AI systems permeate daily life, citizens confront issues of privacy, consent, fairness, and algorithmic influence. Public trust becomes a crucial variable — one that can either accelerate adoption or trigger resistance.

Education systems are under pressure to adapt. Workforces must evolve as automation changes job structures. Legal systems grapple with liability in cases involving autonomous systems. Cultural debates intensify over the appropriate boundaries of machine influence.

In this context, technology is not neutral. The way societies design and govern AI reflects their values — and shapes future generations. The AI cold war is therefore not only about who leads in technology, but also about what that leadership represents.

The path ahead: competition and coexistence

As 2026 unfolds, two realities coexist. The first is that AI competition is unavoidable. Nations will continue to invest, innovate, and secure strategic advantage. Algorithms and chips will remain central tools of power.

The second reality is that coordination is essential. Challenges such as climate change, health crises, and global financial stability require collaboration. So do standards for safety, transparency, and ethics. The world must therefore navigate a paradox: managing competition while preventing fragmentation and instability.

The AI cold war is not a binary conflict with a clear victor. It is an evolving landscape in which power is distributed among states, companies, and institutions. It is reshaping global relations, economic structures, and social norms. Its outcomes will influence how societies live, work, govern, and define progress.

In the end, the real question may not be who leads in AI, but how leadership is exercised — responsibly, transparently, and for the collective benefit. The choices made in 2026 will echo far beyond this year, setting the trajectory for the digital age and determining whether technology becomes a tool of empowerment or division.