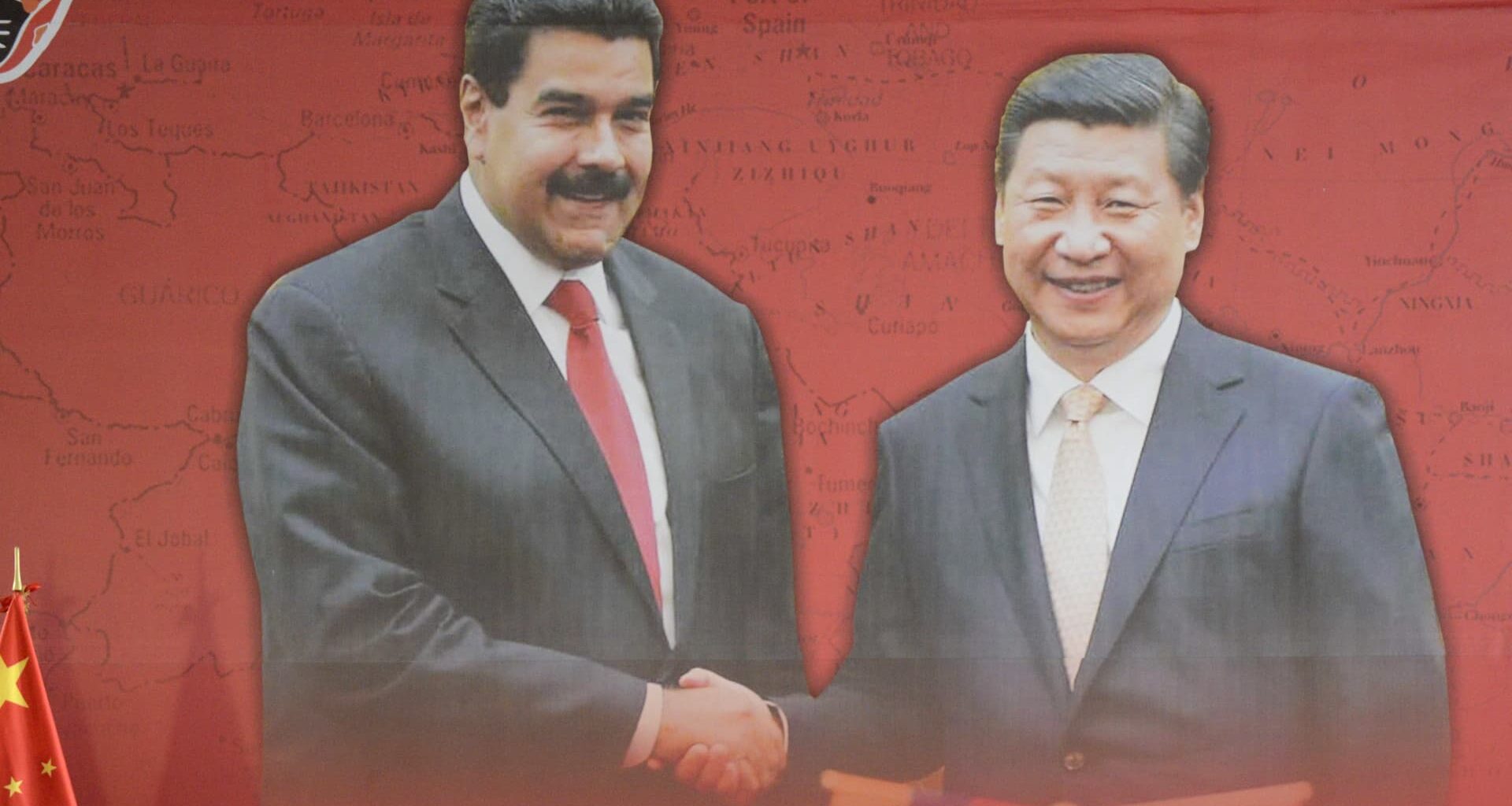

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro (L) and China’s President Xi Jinping wave during a meeting in Miraflores Presidential Palace, in Caracas on July 20, 2014.

Leo Ramirez | Afp | Getty Images

The ancient Greek historian Thucydides once wrote that “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.” On Jan. 3, the United States appeared to echo that maxim when it launched strikes on Venezuela and, in a lightning raid, arrested President Nicolás Maduro and his wife.

The couple was flown to New York to face drug and terrorism charges, drawing sharp criticism from foreign governments about the legality of the attack. The operation also reignited debate over whether Washington is reviving a world where might makes right.

David Roche of Quantum Strategy told CNBC the operation could weaken U.S. arguments against similar actions by rivals.

“If Donald Trump can walk into a country and take it over… then why is Putin wrong about Ukraine, and why is China not entitled to take over Taiwan?” Roche said.

The U.S. has asserted what it calls a “Trump Corollary” in its recently released National Security Strategy, reviving the Monroe Doctrine of the 1820s, where the U.S. had a sphere of influence over the so-called “Western Hemisphere.”

A sphere of influence refers to a region where a powerful country seeks to dominate political, military or economic decisions without formally annexing territory.

The concept echoes the Roosevelt Corollary, which historically justified U.S. intervention in Latin America.

A statement from United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said that he was “deeply concerned that the rules of international law have not been respected,” calling the developments in Venezuela a “dangerous precedent.”

Roche warned the action could create unintended consequences. “On one hand, you’ve created a series of threats, and on the other, you’ve created a series of permissions to every dictatorial, autocratic regime, who wants to act to take over territory which is not currently within its ambit.”

In Asia, attention has turned to whether China could be emboldened to increase pressure on Taiwan, which Beijing considers part of its territory.

China staged live-fire drills around Taiwan in December, framing them as a warning against foreign interference.

In his New Year’s address, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared Taiwan’s unification “unstoppable,” echoing U.S. intelligence assessments that Beijing could attempt to seize the island by force within this decade.

Ryan Hass, a former U.S. diplomat and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, cautioned against drawing direct parallels.

“There will be an impulse among foreign policy analysts to draw analogies to Taiwan and to warn about Trump setting a precedent Beijing could use against Taiwan. I would caution against that impulse,” he wrote on X.

Russian President Vladimir Putin (C), Chinese President Xi Jinping (R), Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro (L) and other leaders lay flowers on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier during Victory Day celebrations on May 9, 2015 in Moscow, Russia.

Sasha Mordovets | Getty Images News | Getty Images

Hass said China has avoided direct military action against Taiwan, not out of deference for international law or norms, but has instead relied on a strategy of coercion short of violence.

“Beijing will be more focused on protecting its interests, condemning US actions, and sharpening the contrast with the US in the international system than it will be on drawing inspiration from today’s events to alter its approach on Taiwan,” Hass wrote.

China’s foreign ministry, in a statement after the strike, said it was “deeply shocked by and strongly condemns the U.S.’s blatant use of force against a sovereign state and action against its president.”

Beijing called the strike a “hegemonic act” and called on Washington to “stop violating other countries’ sovereignty and security.”

“The Trump administration, more so than any American administration in recent memory, is comfortable with great powers like China and Russia having a sphere of influence,” said Marko Papic, chief strategist of macro-geopolitical at BCA Research.

However, it does not mean that Washington is okay with these countries expanding their orbits, he added.

Moreover, there does not seem to be an “abandonment” of Taiwan by the Trump administration, Papic told CNBC’s “Squawk Box Asia“, pointing to the $11 billion arms sale that was announced by Taiwan in December.

The U.S. does not have a mutual defense treaty with Taiwan, but the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act commits Washington to providing weapons necessary for Taiwan’s self-defense.

Evan Feigenbaum of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace argued the U.S. would likely pursue its own sphere of influence while denying one to China.

“The United States is NOT going to ‘consent’ to a Chinese sphere of influence in Asia,” Feigenbaum wrote on X. “Instead, I suspect it will attempt to insist on an American sphere of influence in its own Hemisphere while trying to deny one to China in Asia.”

“Let’s not pretend the U.S. is consistent and that contradiction and hypocrisy in U.S. foreign policy aren’t a thing,” he added in a separate post.

BCA Research’s Papic said that time was on China’s side, and added it did not have to immediately act on Taiwan, while the U.S. is likely to focus on its “Western Hemisphere.”

“Why risk getting the entire Western world to unite against [China] by effectively trying to militarily reunify with Taiwan in January of 2026? Why risk it when time is likely on China’s side over the next 10 years, as the U.S. continues to focus on the near abroad, and less so on the entire world.”

— CNBC’s Chery Kang, Martin Soong and Amitoj Singh contributed to this report.