On the edge of ancient Jerusalem, at a quiet monastic ruin mostly lost to time, archaeologists uncovered a puzzling grave. The tomb, tucked inside a Byzantine-era crypt, contained the remains of a person tightly bound in iron. Chains wrapped around the neck. Others linked the arms, waist, and legs. There were no offerings. No inscriptions. Just rusted metal and brittle bone.

The site had once been part of a monastery. That much was clear. What wasn’t clear, at least at first, was the story behind the skeleton. Monastic ascetics in the Byzantine world are known to have used physical restraints as a form of spiritual discipline, so the burial didn’t seem out of place. It fit a pattern.

But it also didn’t.

After nearly a decade, new scientific tests revealed something no one had expected. The person in chains wasn’t male, as originally assumed. She was female. And that single detail has begun to shift how archaeologists think about gender, devotion, and extreme religious practice in early Christianity.

A Rare Case of Female Religious Self-Restraint

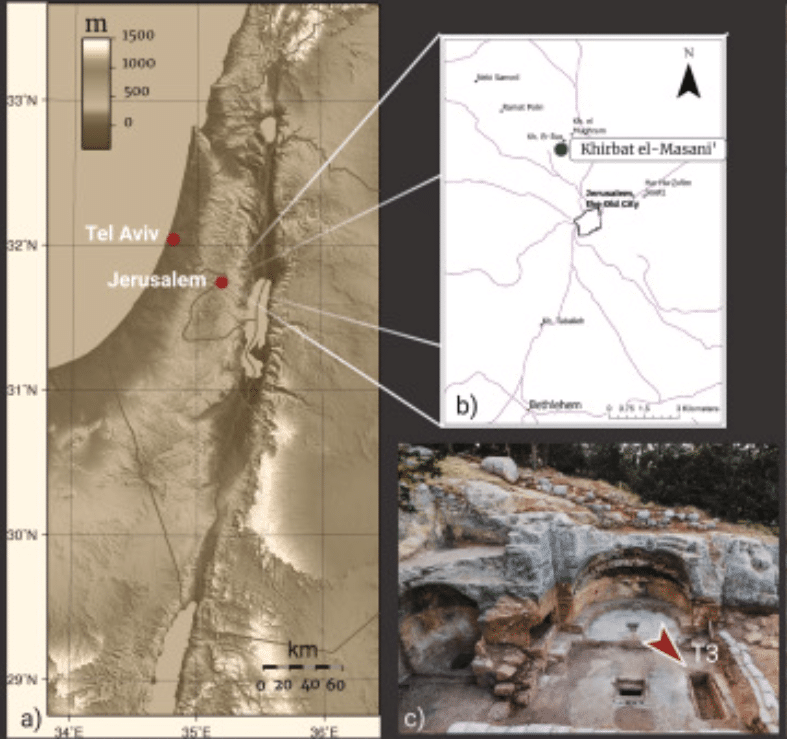

The remains were found in 2017 at Khirbat el-Masani, a ruined monastic compound located around three kilometres northwest of Jerusalem’s Old City. Excavations at the site, led by the Israel Antiquities Authority, revealed several crypts containing men, women, and children—likely members of a Byzantine religious community from the 5th or 6th century CE.

One grave stood apart. Inside, a body had been interred wearing iron chains, not as punishment but as part of a chosen lifestyle. The bones were fragile, partially degraded, and at the time, researchers identified the individual as male. The assumption rested on context. Asceticism that involved self-binding or chain-wearing had been historically associated with male monks and hermits.

That assumption didn’t hold.

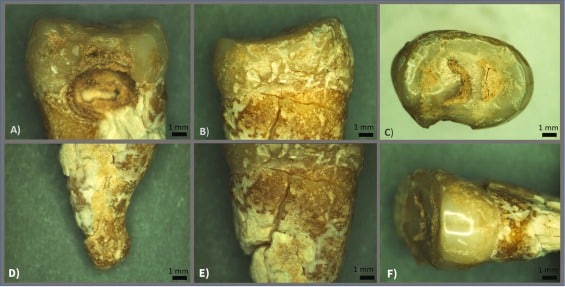

In a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science conducted a peptide-based analysis of the skeleton’s tooth enamel. The test detected the presence of AMELX, a protein encoded on the X chromosome, and no trace of AMELY, which is found on the Y chromosome. This confirmed the biological sex as female.

“It’s much rarer to find accounts of women using chains in the same way,” said archaeologist Elisabetta Boaretto, co-author of the study, in comments reported by Live Science.

The individual was estimated to be between 30 and 60 years old at death. No evidence of trauma was observed, and the distribution of chains suggested they were worn during life, not applied after death.

Context and Contradictions in Historical Records

Historical references to female ascetics exist throughout Late Antiquity. Texts describe women, particularly those from noble backgrounds, who gave up social and economic status to pursue lives of religious devotion. These women often practised celibacy and isolation, but documentation of extreme physical practices, like the use of chains, is limited and fragmentary.

Male ascetics who wore chains, on the other hand, appear more frequently in the historical and religious literature of the period. They often lived in desert cells or secluded monasteries, using physical restrictions to detach from worldly distractions. The use of iron restraints was symbolic of self-denial and a rejection of bodily comfort.

In this case, the burial of a woman with such restraints complicates that narrative. The grave, situated within a monastic compound and arranged with apparent ritual care, may indicate that her commitment to ascetic practice was respected by the community. The chains might not only reflect her personal discipline but also serve as markers of identity in death.

Boaretto explained the spiritual logic of such restraints, noting that by limiting their movements, ascetics aimed to “create space for their minds and hearts to turn solely to God,” as cited in the original Live Science article.

Interpreting Belief Through Bone and Metal

The findings have broader implications for bioarchaeology, a field that increasingly uses molecular techniques to re-examine long-held assumptions. Conventional skeletal analysis often struggles to determine sex when bones are poorly preserved. In such cases, enamel peptide testing provides a more accurate alternative, especially for fragmentary remains from ancient contexts.

The researchers were careful to emphasise that their findings relate only to biological sex, not to gender identity or social roles, which cannot be inferred from protein data alone. Still, the presence of a woman in this burial context, wearing physical restraints once thought to be exclusive to men, raises new questions about the visibility and agency of women in early Christian religious life.

This case may not be isolated. Other burials with ambiguous or untested remains could reveal similar patterns if subjected to advanced analysis. The use of chains, once considered a marker of male asceticism, may have been more widespread, but misclassified due to assumptions in older scholarship.