Last Updated on January 5, 2026

The last remaining uranium mill in the United States is located in White Mesa, Utah. The White Mesa Uranium Mill, owned and operated by Energy Fuels, processes uranium-bearing materials into yellowcake, a key component of nuclear reactor fuel.

Mill tailings are the liquid radioactive byproduct of this process, and carry a serious environmental impact. This liquid is stored on-site in massive impoundments carved into the desert landscape.

They are carved into land sacred to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is one of three tribes within the larger Ute Nation that inhabit the Four Corners region of the Southwest. It has communities in Colorado and in White Mesa, Utah. The Tribe counts approximately 2,100 enrolled members, about 250 of whom live in White Mesa. As a sovereign Nation, the Tribe is self-governed and works to protect its homelands, history, and culture.

For two decades, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has actively resisted the operations of the White Mesa Uranium Mill that is contaminating ancestral lands with radioactive waste and jeopardizing its future. They have protested mill operations by building coalitions, organizing spiritual walks and peaceful protests, and educating social sectors through social media.

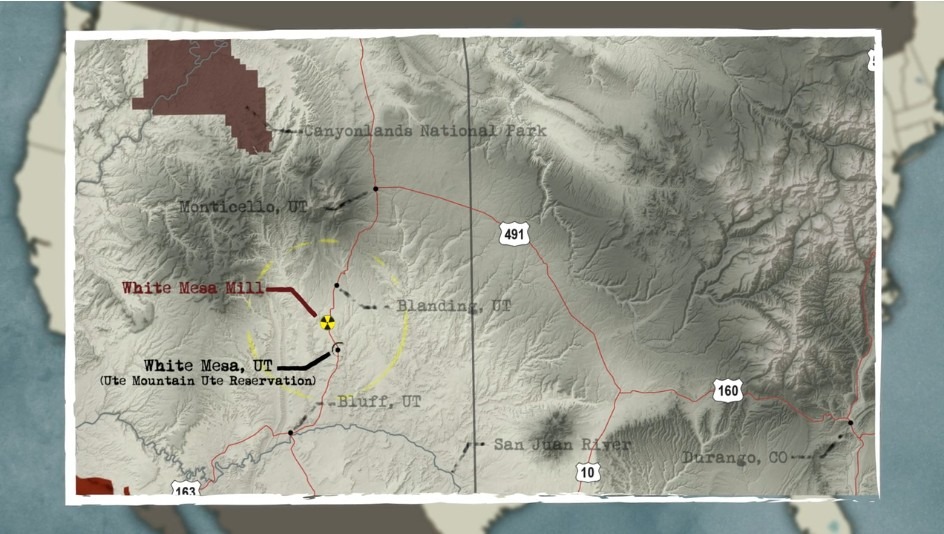

Map from the film, Half Life: The Story of America’s Last Uranium Mill

The White Mesa Concerned Community, along with a coalition of organizations, recently called on Utah’s Governor Spencer Cox, “to assume responsibility and take action to establish long-term, safe, and equitable solutions for radioactive waste disposal.” The Tribe has fought over multiple generations, but state agencies and corporate actors continue to ignore their voices.

Each October, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe organizes an annual spiritual walk through the homelands to the gates of the White Mesa Uranium Mill, with elders, youth, and families praying, singing, and making offerings along the route. At the front of the walk, tribal members hold a sign that reads “No Uranium. Protect Sacred Land.”

Ofelia Rivas of the Tohono O’odham Nation said: “Every step that you take on this Mother Earth is a sacred step… Every inch of this Mother Earth, this Turtle Island, has remains of our ancestors… The prayer walk is a solidarity walk”.

The White Mesa Mill is one of many nuclear operations that destroy land to the point of no return. Historically, Indigenous lands have been treated as sacrifice zones. This pattern is known as “nuclear colonialism” — a system in which Indigenous lands are targeted for uranium mining, milling, and nuclear waste disposal. Rooted in settler colonial politics, nuclear colonialism works to eliminate Native peoples in order to appropriate their lands.

Environmental contamination that makes land unlivable reveals the systematic structure of nuclear colonialism. This system undermines Native governance while making Native lands expendable. High amounts of uranium waste make Indigenous lands uninhabitable while sustaining state and corporate interests tied to the U.S. military–industrial complex. The harm caused by nuclear extraction is therefore the result of a political system that concentrates power with the state and industry while sacrificing Indigenous land and peoples.

White Mesa’s Endless Nuclear Life

When it first opened in 1980, the mill was proposed to the community as a fifteen-year facility. Now, there’s no end in sight. Its long-term operation has devastated the surrounding environment. Thema Whiskers, a Ute Mountain Ute Tribe elder, speaks of how the land once was. “Up that way it used to be nice and green, and [in] springtime, I used to get native tea. And we used to have a lot of prairie dogs, and we used to have rabbits, too. There’s nothing now. It’s all gone.” The loss Whiskers describes is the consequence of radioactive waste storage.

Radioactive waste will remain on Ute lands indefinitely.

All nuclear operations in the United States are federally monitored by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). Yet, local states can choose to opt in as an Agreement State to gain primary authority to “license and inspect byproduct, source, or special nuclear materials used or possessed within its borders.” This reduces federal oversight, placing authority in the hands of state agencies more malleable to industry interests by creating regulatory gaps. This regulatory structure enables nuclear colonialism by allowing industries to operate on Indigenous land without accountability.

White Mesa’s facility was designed to mill local uranium ore, but Energy Fuels soon discovered regulatory loopholes that allowed it to use the site as a radioactive dumping ground. The mill began importing radioactive uranium-bearing waste from nuclear facilities across the country, as well as from sites in Japan and Estonia.

The Utah Department of Environmental Quality amended its policies in 2020, stating that “The licensee may not dispose of any material on site that is not ‘byproduct material’.” So, if the mill extracts some last bit of uranium from imported waste, it can legally dispose of it.

The White Mesa Uranium Mill is increasingly operating as a low-level radioactive waste disposal site, despite its legal classification as a mill.

“The White Mesa Mill is behaving as if it’s a low-level radioactive waste dump, and it should be regulated like one,” says Tim Peterson, a director at the Grand Canyon Trust. The decision to move operations without consulting Indigenous nations is an instance in which colonial powers manipulate Indigenous communities to appropriate their lands.

This nuclear waste will contaminate the Ute Mountain Ute land for centuries.

So much for a fifteen-year facility.

The Mill’s Odorless Killing

The mill operates just five miles from the edge of the Ute Mountain Ute territory, affecting tribal families. Journalist Jessica Douglas reports that community members have noticed their water is becoming more acidic and the air has a strong sulfur smell. One Tribe member says, “A lot of our younger members now have asthma,” adding, “we’re losing a lot of elders due to health issues.”

The impoundments (engineered containment ponds) of radioactive waste carry dangerous environmental and health risks as they seep into underground aquifers. The presence of sulfuric acid makes groundwater more acidic. The pH level of the sulfuric acid byproduct in mill tailings ranges from 1.2 to 2.0, significantly more acidic than the pH level of standard drinking water, which typically ranges from 6.5 to 8.5.

Acidic drinking water poses a serious risk to humans, as well as to the animals and plants that inhabit the land. Metals in the water cause dental issues, nausea, and organ damage. They kill fish, harm animals, and damage soil.

Although the pH of the water in the White Mesa community hasn’t yet fallen outside the range recommended by the EPA, the tribal council has voiced concerns about its water’s future. They worry about contaminating ancestral land where generations were and will continue to be raised. “We always speak of our unborn children… they’re the ones we’re looking out for,” says council member Malcolm Lehi during a protest.

Uranium Globally

White Mesa is not alone. Uranium milling harms communities worldwide.

Radon gas is naturally produced as uranium breaks down in soil. The inhalation of this gas is harmful to humans and causes lung cancer. Yet, its odorless and colorless properties make it a silent killer.

Uranium milling in Kazakhstan has exposed communities to radon for far longer than the mill at White Mesa. The country accounts for over 40% of the world’s uranium production. In Stepnogorsk, approximately 70,000 people are exposed to radon through the air. Of the 132 homes inspected, 32 contained a radon concentration higher than 200 Bq/m3. In the United States, 150 Bq/m3 is considered dangerous to human health. Locals grow fruits and feed animals on the affected land, threatening an additional 30,000 people. Their lived experiences are a glimpse into the future for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.

Across the United States, thousands of uranium mines sit abandoned, 500 of which are on the Navajo Nation alone. Although abandoned, the mines continue to release radioactive contaminants, including radon gas, into the air and water. This poses a significant health hazard to surrounding communities.

During the Cold War, the U.S. government mined Navajo lands for uranium, fueling nuclear operations. The Navajo people were offered economic opportunities, but the consequences were not explained. The mines where Navajo workers were employed had inadequate ventilation, limited protective gear, and miners were not informed of the risks. The harm spread beyond the mines as homes were constructed using unknowingly contaminated uranium materials. Families relied on water sources that flowed with radon.

Decades later, the consequences remain. The Navajo Nation has named the harm in its own words. “Cancers, miscarriages, and mysterious illnesses have plagued our community for decades.” Economic prosperity often serves as a front for the devastation of lands that accompanies nuclear operations.

This manipulation technique, used by governments on Indigenous nations, makes the short-term benefits seem appealing while hiding long-term harm. “The only job that was really available in our area were the mines” says Larry King, a member of the Navajo Nation and former mine worker.

Today, the Navajo Nation continues to fight for justice. In 2024, more than 70 Navajo citizens traveled to the U.S. Capitol to demand accountability through the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which provides limited compensation to some individuals harmed by uranium mining. But financial reimbursement cannot solely compensate decades of preventable illness and death. Real justice lies in the cleanup of contaminated lands and the restoration of Indigenous sovereignty over health, water, and territory.

This is the pattern of nuclear colonialism. From the Navajo Nation to the Black Hills and Grand Canyon, systematic nuclear operations continue to undermine Indigenous lifeways.

Green Nuclear Settler Colonialism?

The nuclear energy sector presents itself as a greener option, yet the White Mesa Uranium Mill proves there is nothing green in nuclear settler colonialism. The Utah Department of Environmental Quality is quick to change regulations for corporate profit. The wider community looks away because the impact falls on Indigenous communities. Soon, even national parks may become sites of nuclear operations.

On November 14th 2025, the U.S. added uranium to its list of critical minerals, meaning federal support for uranium production will increase. The fight will become more challenging. Federal lawmakers recently moved to expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, but compensation alone doesn’t stop the contamination of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.

Without confronting nuclear colonialism, policies will continue to produce harm.

Manuel Heart, chairman of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, spoke at the Southwestern Water Conservation District Press Conference. “We should all have access to clean water, and we need to be able to not just say it, but put it into action. We need to include them [sovereign tribes] in legislation and advocate for one another.”

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe recognizes the devastation already caused, but is focusing on the consequences yet to come, advocating for the generations that will someday inherit all this nuclear waste.

This article is a part of Hotspots, a journalistic collaboration between IC, Professor Manuela Picq and her students at Amherst College.