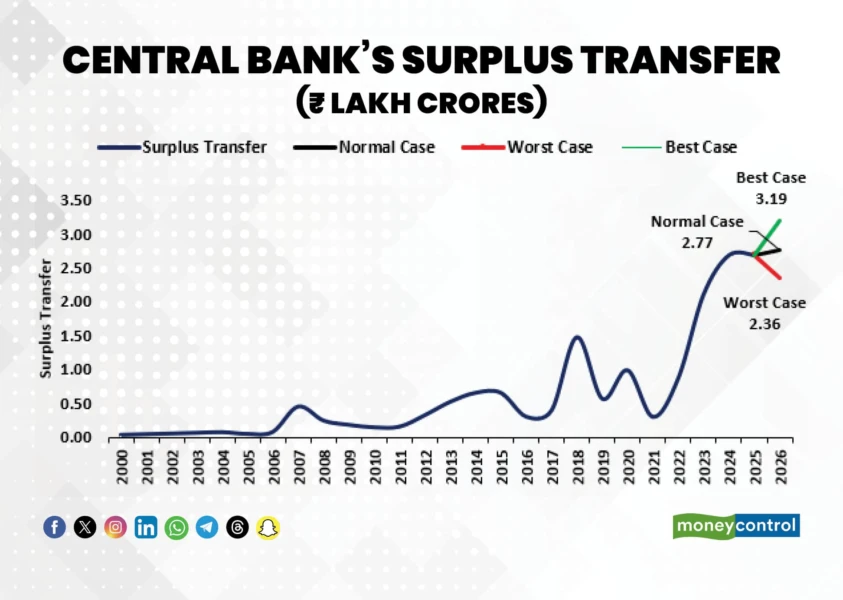

India’s budget has quietly become accustomed to an unlikely supporter: the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). Over the past two years, the central bank’s dividend payments to the government have surged to unprecedented levels – from roughly ₹87,000 crores in FY23 to over ₹2.1 lakh crore in FY24, and then about ₹2.7 lakh crore in FY25. These transfers have become a silent tool for managing fiscal policy. The additional funds have helped keep India’s fiscal situation stable, reducing the budget deficit by nearly 0.2% of GDP last year. However, these windfalls are more the result of exceptional market conditions than steady fundamentals. As global conditions shift, how extensive a cheque will the RBI issue for FY26—and can Delhi rely on these transfers?

RBI’s Surplus: A Result of Exceptional Market Conditions

The central bank’s balance sheet now generates unexpected revenue. In FY25, a combination of factors created a “perfect storm” that boosted the RBI’s profits. Rising US interest rates suddenly made the central bank’s extensive foreign-bond holdings profitable — overseas interest income increased nearly 30% compared to the previous year. Domestically, very high interest rates (with the repo rate at 6.5%) meant the RBI earned substantial income from lending to banks. The most dramatic factor was FX intervention: amid a hefty current-account deficit and capital outflows, the RBI sold approximately $400 billion to stabilise the rupee. Each dollar sold was worth more rupees than when bought, resulting in a significant forex gain. Operating costs remained almost unchanged, so nearly all of these extraordinary gains contributed directly to the bottom line. The outcome was a record surplus, leaving roughly ₹2.7 lakh crore available for transfer to the government.

Why Payouts Have Soared

Recent years of high dividends are due to conditions that may not happen again—first, oil. Until recently, high global oil prices increased India’s import costs and inflation, which hurt the rupee. Now, oil prices have dropped significantly (even after some OPEC cuts), helping India’s current account and reducing inflation. A lower oil bill means the rupee is less likely to fall.

Second, the dollar. The US Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate hikes made the dollar very strong for much of FY25, weakening the rupee. The RBI intervened heavily, locking in profits when the rupee later slipped. But the Fed seems closer to pausing—or even cutting—rates in 2025. A weaker dollar ahead would likely strengthen the rupee. That’s good news for the economy, but not for central bank earnings: a strong rupee means fewer rupees when dollars are sold and also results in lower interest on new dollar deposits. In short, the tailwinds for RBI’s profits could fade.

Third, volatility. Global turmoil, such as geopolitical conflicts, tariff skirmishes, or unexpected shocks, can actually boost RBI profits by triggering capital flows into and out of India. In short, the external environment is becoming less extreme. Meanwhile, on RBI’s own balance sheet, there has been a strategic shift: its gold holdings have increased to nearly 10% of reserves. Gold is a safe buffer against risk, but it does not generate interest income. As gold’s share rises, the yield on RBI’s total assets declines. All these developments suggest a likely slowdown in RBI’s earnings growth for FY26.

Scenarios for FY26 Dividend

Looking ahead to FY26, the RBI’s surplus could come in a range depending on how these trends play out. Broadly speaking:

1) Windfall: Suppose global rates remain high or even increase, the Fed keeps monetary policy tight, and India’s current account stays in deficit. In such a scenario, the rupee would stay under pressure, prompting higher market intervention. Additionally, steady domestic interest spreads could keep RBI income very high. If, furthermore, the RBI chose to operate with only the minimum risk buffer, say by holding its contingency reserves at the low end (around 5.5–6% of its balance sheet), the government’s dividend could rise to roughly ₹3.1–3.3 lakh crore. This outcome is ambitious and akin to turning today’s global headwinds into tailwinds for the RBI profits.

2) Baseline: The Fed is expected to start rate cuts by late 2025, oil prices stay relatively stable, and the rupee gradually gains strength. The RBI’s interventions are less aggressive than last year. Domestic interest rates may also decline as inflation cools, potentially lowering the RBI’s lending income. Under these conditions, the surplus will remain significant but closer to last year’s level. A dividend of around ₹2.6–2.8 lakh crore is expected. This is roughly in line with FY25, perhaps slightly lower, indicating that only part of the boom continues.

3) Reversion: If global markets stabilise faster than expected, US rates decline sharply, the dollar weakens significantly, and India shifts to a trade or current-account surplus—the rupee could strengthen. Oil prices might also rise again (due to new OPEC cuts or conflicts), which could feed into inflation. In that scenario, the RBI would likely not need to intervene in forex markets, and its rupee holdings would earn less on foreign assets. Combined with potentially lower domestic rates, the RBI’s profits could decrease considerably. Quantitatively, the FY26 dividend could fall below ₹2.4 lakh crore, possibly into the ₹2.0–2.2 lakh crore range in an extreme case. That would be a return to the mean of the last two years.

Based on our forecast using a polynomial fit of RBI’s income, expenses, and balance sheet size, applied in conjunction with the Jalan Committee’s surplus transfer formula, we estimate the FY26 dividend could range from ₹2.36 lakh crore in a pessimistic scenario to ₹3.19 lakh crore in an optimistic one, with a base case projection of ₹2.77 lakh crore. The model’s R-squared, ranging between 93% and 99%, indicates a strong historical fit and lends confidence to these scenario-based estimates.

Fiscal Implications and Budget Planning

Last year’s RBI payout accounted for 0.2% of GDP, more than expected, adding over ₹50,000 crores to ease the deficit. If similar surprises happen in FY26, it could give India more fiscal space to spend or borrow. Conversely, if RBI transfers fall, the government would need to raise nearly ₹10,000 crores for every 0.04% of GDP shortfall, roughly ₹80,000–₹1,00,000 crore for a deficit increase of ₹50,000 crores.

It’s wise to view RBI dividends as one-off gains from unique conditions, not a given flow. Relying on them routinely is like budgeting with out-of-cycle gains. While high dividends can temporarily ease borrowing or support growth through increased capital or infrastructure spending, the uncertain global rate environment, geopolitical shifts, and a weaker RBI revenue outlook suggest it’s risky to count on last year’s record again.

Planning for the Unknown

The RBI’s surplus has become a powerful yet unpredictable financial cushion. In FY25, it offered vital support, but only under conditions that might not persist—such as falling oil prices, a strong dollar, and aggressive global rate hikes. When these factors change direction, the surplus transfer would decline in FY26.

Given this uncertainty, fiscal planners should adopt a prudent approach, budgeting for a conservative dividend estimate and treating any upside as opportunistic capital. Rather than committing surplus funds to recurring subsidies or routine expenditure, these windfalls should be directed toward assets that appreciate over time and deliver long-term returns. This could include expanding logistics infrastructure, co-investing in strategic semiconductor or battery manufacturing, modernising railway corridors, or supporting skill development programmes. Channelling one-off gains into such productivity-enhancing sectors not only strengthens the growth engine but also reduces the economy’s future reliance on unpredictable revenue streams.

Ultimately, while the RBI’s support has been invaluable, it must remain a supplementary tool. Windfalls may be fleeting, but if invested wisely, their impact can be enduring.

(V Shunmugam is Partner, MCQube and Yatharth Sharma is Emerging Scholar in Finance, National Institute of Securities Markets.)

Views are personal, and do not represent the stance of this publication.