In the beginning, not all amateur galaxies were winners. Scientists have now found one of the duds that just couldn’t hack it in the wild early days of the universe.

Near the spindly spiral galaxy Messier-94, about 14 million light-years away in space, astronomers have found a small, spherical ghost town. For years, scientists have looked for evidence of such a phantom, proposed by theory. It wasn’t until they pointed NASA‘s Hubble Space Telescope at the cloud that they discovered the first example of a primitive galaxy that never had the gumption to form stars.

Radio telescopes first picked up its faint signal of neutral hydrogen in 2023. Scientists gave it a name, Cloud-9 — and it was indeed the ninth cloud detected around M94 — then wondered what exactly held this thing together.

Before Hubble, researchers could rationalize that the object was merely a tiny dim galaxy whose stars were just too faint to see through the eyes of ground-based telescopes, said Gagandeep Anand, a staff scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

“But with Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys, we’re able to nail down that there’s nothing there,” he said in a statement.

Neutral hydrogen — that’s ordinary hydrogen whose electrons haven’t been stripped away — could not hold Cloud-9 together. The mysterious object, about 4,900 light-years wide, contains about 1 million suns‘ worth of hydrogen — not nearly enough to keep the cloud from scattering.

That means something unseen must provide the weight. The simplest answer, according to the research team, is dark matter, the invisible scaffolding thought to manage nearly all cosmic construction. Their findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Mashable Light Speed

Left:

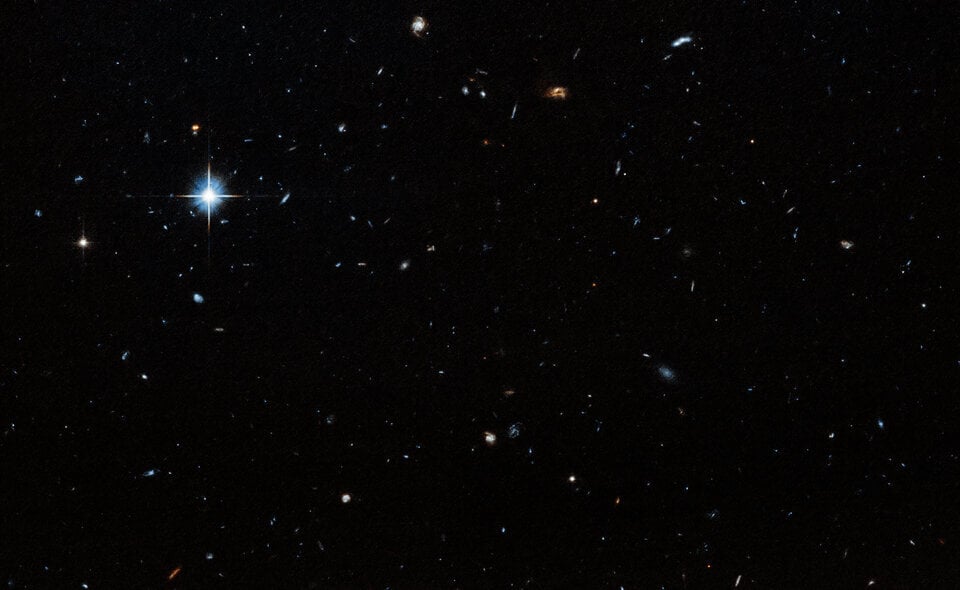

Swipe the slider bar to the left to reveal Cloud-9 amid this blank field of space.

Credit: NASA / ESA / VLA / Gagandeep Anand / Alejandro Benitez-Llambay / Joseph DePasquale

Right:

The Very Large Array telescope detected radio emissions from Cloud-9, indicated here in magenta. The circled area, where scientists found peak radio data, contained no stars. The specks of light in this image come from background galaxies.

Credit: NASA / ESA / VLA / Gagandeep Anand / Alejandro Benitez-Llambay / Joseph DePasquale

Because studies strongly indicate that Cloud-9 is a starless, gas-rich, dark-matter halo, it provides precious insight into the mysterious-yet-pervasive substance in the universe, said Andrew Fox, a co-author affiliated with the European Space Agency.

“This cloud is a window into the dark universe,” Fox said in a statement. “We know from theory that most of the mass in the universe is expected to be dark matter, but it’s difficult to detect this dark material because it doesn’t emit light.”

Scientists have theorized that dark matter clumps exist in staggering numbers, far more than the galaxies we see. Only clumps that exceed a certain threshold in mass should hold onto gas and ignite stars. Below it, gravity loses its tug-of-war with heat and radiation, and star formation can’t occur.

Based on this prediction, many galaxy failures — gassy spheres devoid of stars — should exist. Astronomers have hunted for proof for years. Most candidates reveal themselves, sooner or later, as ordinary gas clouds in the Milky Way or as faint galaxies hiding their stars.

This Tweet is currently unavailable. It might be loading or has been removed.

But Cloud-9 is different. Its gas moves serenely through space. It shows no sign of spinning into a disk, which usually means stars are around. Its mass places it close to that theoretical boundary where a galaxy should either eke out — or not form at all.

The team did not stop at Hubble. They ran many computer simulations, planting fictitious galaxies of varying sizes into the data to test whether the observatory could have detected them. If Cloud-9 contained even a paucity of stars, the telescope would have seen it, according to the study.

No glittering swarm. No smear of light. Researchers calculated that Cloud-9’s dark matter must be equal to about 5 billion suns in mass. It appears to stand at the very precipice of galaxyhood, said Alejandro Benitez-Llambay, the study’s principal investigator.

“In science, we usually learn more from the failures than from the successes,” said Benitez-Llambay, a scientist at Milano-Bicocca University in Italy, in a statement. “In this case, seeing no stars is what proves the theory right.”