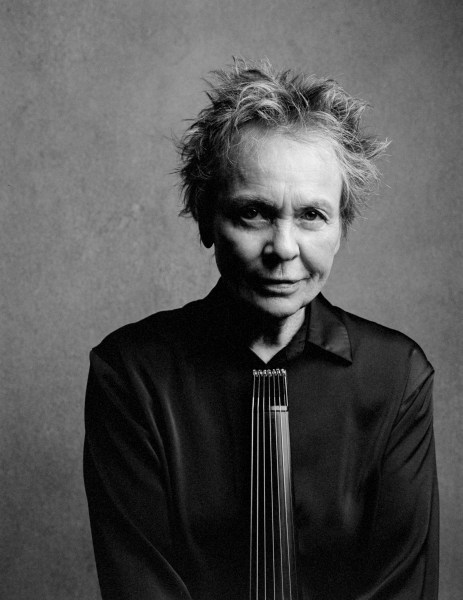

American polymath Laurie Anderson’s travels time in her Reykjavík performances

Reykjavík plays host to a Laurie Anderson residency this week as the revolutionary polymath performs two shows at Steina Vasulka’s retrospective in addition to her standalone Republic Of Love show at Harpa. Her contributions to the Steina exhibition, which has taken over two of the main art museums in town for the last couple of months, come in the form of a sound installation called Lou Reed Drones at the Reykjavik Art Museum and a concert featuring violist Martha Mooke and multi-instrumentalist Eyvind Kang at the National Gallery of Iceland.

The concert is dubbed Three Violas, but Anderson is unlikely to pick up a bow. “They said, ‘Do you want to play her violin?’ and I was like, ‘No, no, no. That would be for me, I don’t know, kind of sacrilege,” Laurie begins.

The refusal is not solely sentimental though as Anderson did recently undergo a shoulder operation due to nerve damage caused by her own “super heavy” custom instrument. “I went to a sports doctor,” she tells me. “All the other people there were like football players and tennis players, and they’re like, ‘What are you here for?’ and I was like, ‘Violin,’” she laughs. “So anyway, I said no to playing the violin.” This is quintessential Anderson disruption. The avant garde auteur’s career is famously un-sum-up-able.

She’s the inventor of a violin that plays magnetic tape; performed a canine-only concert at the Sydney Opera House; became NASA’s first and only artist in residence; and rewrote the Bible in her own voice. Five decades into her career she became a viral sensation on TikTok with “O Superman”, a song that made her an accidental popstar in the early 80s. Laurie Anderson is not linear.

Exploring the edge with Steina

“I’m not a good analyst of what I’m doing. I really try to make a kind of interesting plan, and then not be afraid to just not do it at all,” she admits when discussing Three Violas. In fact, the plan will only be made “the morning of” when Anderson will finally get an opportunity to experience Steina’s exhibition first hand: “Nobody will know until it happens, and even then they may not know,” she says with a wry smile.

“I was a minimalist sculptor at the time. I found meaning in plywood leaning against a wall at a certain angle.”

Anderson’s embrace of the unknown can be traced back to a New York scene of likeminded edge-obsessers that found shelter in The Kitchen back in the early 70s. Founded by Steina and Woody Vasulka, The Kitchen was established in New York City’s Mercer Art Center, an early adopter of the co-working/community spaces we have grown too accustomed to half a century later, but at the time a revolutionary idea.

A mismatch of visionaries in the fields of theatre, music and visual arts took over a couple of floors of the crumbling Grand Central Hotel on Broadway and gave birth to some of the most influential art scenes of the 20th century.

“I was a minimalist sculptor at the time,” Anderson recalls. “I found meaning in plywood leaning against a wall at a certain angle. We had endless discussions about what the ‘edge’ was, and what stepping over the edge would be.”

While Anderson and cohorts searched for the edge, the building did indeed step over it. In the summer of 1973 the Grand Central Hotel collapsed into rubble, taking Mercer Art Center with it. The Kitchen had fortuitously relocated to Soho prior to the building’s disastrous fate and remains a vital venue for progressive arts.

“The Kitchen was so important to so many young artists,” Anderson tells me. “It was the only place we could play. It was a really close-knit community and we never thought we would make a living doing this. It had nothing to do with anything financial at all. We had our spaces, and we had our pickup trucks, and we built things.”

Hunting whales with Skúli Sverrisson

It was through one of her most audacious projects to date — an attempt to make the oceanic sprawl of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick into a techno-opera — that she encountered Icelandic bass virtuoso Skúli Sverrisson for the first time. “He is a band,” Anderson says of Skúli. “He can do so many beautiful, atmospheric things.”

“For me, the biggest freedom has been the freedom to use time in a really different way.”

The pair, who collaborated on Songs and Stories from Moby Dick and later the album Life on a String, where Skúli took the role of musical director, joined forces for the first time in a couple of decades at the Reykjavik Art Museum for Lou Reed Drones. The installation is decidedly louder and more visceral than their previous collaborations and utilises a wall of feedback generated by a collection of Anderson’s life partner’s — and late rock god’s — personal gear. Alongside Skúli, Anderson has recruited Sigur Rós’s Kjartan Sveinsson and local legend Davíð Þór Jónsson to man the controls.

Time travels through Big Science

“I’m more trusting of improv lately,” Laurie reflects. “I sometimes find it super boring to listen to people sleepwalking around looking for notes. But when they find it, it’s fun to hear. I’d rather hear them find it than just hear them repeat the same thing they did last night.”

This newfound trust in the search for “the notes” is what has transformed Republic of Love from a two-hour talk she gave in 2024 at the Free Republic of Vienna Festival on the topic of love and government. It’s an assignment she admits felt “pretty tedious” at times. “I think I’m going to change it almost completely, because it’s just too many words,” she says. “When I’m in an audience, I am lazy. I would rather hear music and read about that stuff later.”

Again, the show is unlikely to rely heavily on Anderson’s virtuosic violin playing as she seems keen to lean on the technology that’s finally caught up with the nonlinearity of her process. “It’s so important to me that, with the equipment I have now, I can go from any point to any point, at any point. You might think that’s terrible, to be afloat with no structure, but you can always put the structure back in. You’re just not obliged to. For me, the biggest freedom has been the freedom to use time in a really different way.”

To achieve that, Anderson is bringing a, “crazy, pretty powerful little bunch of sounds,” she says, pointing to the back of the room to the heap of hi-tech synths and unidentifiable gear resembling a small spaceship. Armed with her time-traveling tools, Anderson plans to revisit some of her past: “We’re resurrecting some older pieces that deal with the themes of government and love. I’m looking at these lines from Big Science that I haven’t sung in 40 years. Lines like, ‘Every man for himself’. What does that really mean now? Even the phrase ‘Big Science’ just has a different ring to it.”

Whatever Anderson is planning, we’re unlikely to find out until it happens, and even then we might not.

Laurie Anderson kicks off her Republic of Love tour at Harpa on Wednesday evening, January 7. A few hours before, Laurie’s Lou Reed Drones is on at Reykjavík Art Museum’s Hafnarhús. Finally, the artist performs Three Violas at the National Gallery on Thursday, January 8, from 20:00-22:30.