Key Points and Summary – Nuclear-powered submarines offer extraordinary endurance, but when refueling finally arrives, it is a painstaking industrial event—not a simple “fill-up.”

-The boat must be placed in dry dock, powered down under strict radiation controls, and opened up so specialists can access a reactor buried behind heavy shielding.

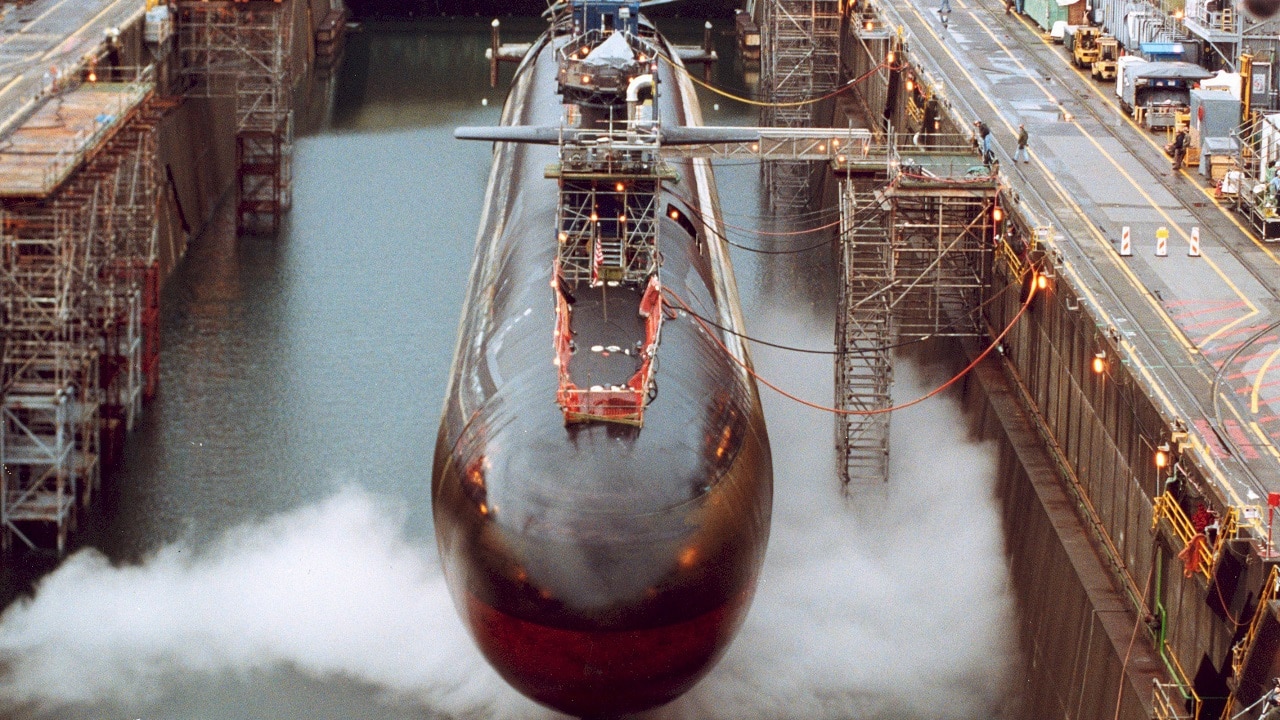

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Wash. (Aug. 14, 2003) — USS Ohio (SSGN 726) is in dry dock undergoing a conversion from a Ballistic Missile Submarine (SSBN) to a Guided Missile Submarine (SSGN) designation. Ohio has been out of service since Oct. 29, 2002 for conversion to SSGN at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Four Ohio-class strategic missile submarines, USS Ohio (SSBN 726), USS Michigan (SSBN 727) USS Florida (SSBN 728), and USS Georgia (SSBN 729) have been selected for transformation into a new platform, designated SSGN. The SSGNs will have the capability to support and launch up to 154 Tomahawk missiles, a significant increase in capacity compared to other platforms. The 22 missile tubes also will provide the capability to carry other payloads, such as unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and Special Forces equipment. This new platform will also have the capability to carry and support more than 66 Navy SEALs (Sea, Air and Land) and insert them clandestinely into potential conflict areas. U.S. Navy file photo. (RELEASED)

Image of US Navy Attack Submarine in dry dock.

-Crews remove and log large sections of equipment, cables, and hardware before the core is even reachable.

-After fuel replacement, the submarine is rebuilt, resealed, tested, and typically modernized with new systems—often turning refueling into a broader overhaul.

-The result is a long downtime that directly impacts fleet readiness, even for a navy with a large submarine inventory.

Why Do Nuclear-Powered Submarines Take So Bloody Long to Refuel?

Besides stealth, one of the great advantages of nuclear-powered submarines over their diesel-powered counterparts is their extended endurance.

However, nothing is perfect, or as Professor Emeritus Dr. Peter Gordon was fond of telling his macroeconomics students at the University of Southern California, “There are no solutions, only trade-offs.” Accordingly, the trade-off of the nuclear subs’ extended endurance is that when the time finally does come to refuel, it takes seemingly forever to do so.

Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

A major source of inspiration for this article is a December 29 piece in Interesting Engineering by Ameya Paleja, who starts his article with a catchy sentence even civilian motorists with no prior military experience will find relatable: “If you are a bit disappointed by how long it takes to recharge your electric vehicle, then the refuelling time of a nuclear submarine could bring you to your wits’ end.”

But why does refueling a nuclear sub take such a long time?

As Ameya explains in layman’s terms, “The nuclear reactor isn’t like an internal combustion engine. Fill the tank with fuel, and you are ready to go. Even on land, refuelling a nuclear reactor can take a few weeks. But for a nuclear-powered submarine, the operation is even more difficult.”

Initial Steps

-For starters, the sub has to be removed completely from the water and placed in a dry dock. It must then be powered down inside a radiation-shielded facility, because of the highly enriched uranium fuel that fuels it.

Ohio-class SSGN Submarine. Image Credit: US Navy.

STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA, Wash. (Aug. 12, 2012) The Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine USS Nebraska (SSBN 739) prepares to conduct a personnel transfer as it returns to its homeport of Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor, Wash. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. Ed Early/Released)

Ohio-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine. Image Credit: US Navy

-The reactor is ensconced behind thick radiation shielding deep inside the hull. To access the reactor, significant portions of the shielding must be removed, a job that can be done only by a team of experts specializing in radiation safety, weapons systems, nuclear engineering, and naval architecture.

This makes the process both costly and time-consuming.

Most of the components are also stripped out. Every single panel, cable, and bolt removed is logged, tracked, and inspected.

Next Steps

Only once all these tasks are completed and the reactor core has been made accessible can the work crews finally get around to the actual act of refueling. Once the fuel is replaced, the team must reinstall the components and reseal the vessel for underwater operations.

In addition, this time is used to replace crew members and restock supplies.

From there, the subs go through an overhaul to ensure that they have the most up-to-date technologies (U.S, Navy submariners definitely do not want their boats to lag behind the Russian and Chinese navies’ subs in that regard). This overhaul is even more time-consuming than the refueling procedure, as the new system needs to be assessed and tested, and the vessel’s integrity fully verified, before it is put back in service.

A case in point is the USS Louisiana (SSBN-743), which underwent a major overhaul that lasted 40 months before the vessel was finally seaworthy again in 2023.

Surface Warship Analogy: RCOH

The lengthy refueling of nuclear submarines is somewhat reminiscent of a rigamarole Navy’s largest and most powerful surface warships must go through. Every 25 years, nuclear-powered aircraft carriers undergo a procedure called Refueling Complex Overhaul (RCOH). It involves cutting a massive hole in the supercarriers’ hulls and replacing everything from catapult systems to water purifiers.

Effect on Fleet Readiness

Fortunately, there are far more nuclear subs in the U.S. Navy fleet than there are nuclear carriers; 68 vs. 11. At any given time, one-third of the CVNs are undergoing RCOH maintenance while one-third are preparing for deployment, which means that only three to four are typically out to sea.

Assuming, for argument’s sake, that the SSNs/SSBNs/SSGNs were on that same “rule of thirds” rotation, that would still leave 22 of these deadly submersibles ready to do battle.

About the Author: Christian D. Orr, Defense Expert

Christian D. Orr is a Senior Defense Editor. He is a former Air Force Security Forces officer, Federal law enforcement officer, and private military contractor (with assignments worked in Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kosovo, Japan, Germany, and the Pentagon). Chris holds a B.A. in International Relations from the University of Southern California (USC) and an M.A. in Intelligence Studies (concentration in Terrorism Studies) from American Military University (AMU). He is also the author of the newly published book “Five Decades of a Fabulous Firearm: Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Beretta 92 Pistol Series.”