Russia today is driven less by triumph than by unease, argues Andres Vosman, until recently Estonia’s top analyst on Russia, in an interview examining the Kremlin’s growing fear of what comes next.

The blunt diagnosis was offered by Vosman, until recently Estonia’s leading Russia analyst at the Foreign Intelligence Service and now ambassador to Israel, in an extensive interview first published in Eesti Ekspress, an Estonian weekly.

According to Vosman, the dominant emotion in Russian society today is not faith, hope or patriotic zeal, but anxiety – a mood confirmed even by Russian bookshop polls. After 15 years of economic stagnation, rising repression and relentless propaganda, many Russians are asking where the promised victory has gone. Public dissent is muted, he says, not because belief is strong but because apathy, self-censorship and “switching off” have become survival strategies. In many respects, Russia has slid back into a late-Soviet condition – though whether it resembles 1937 or 1984 remains an open and ominous question.

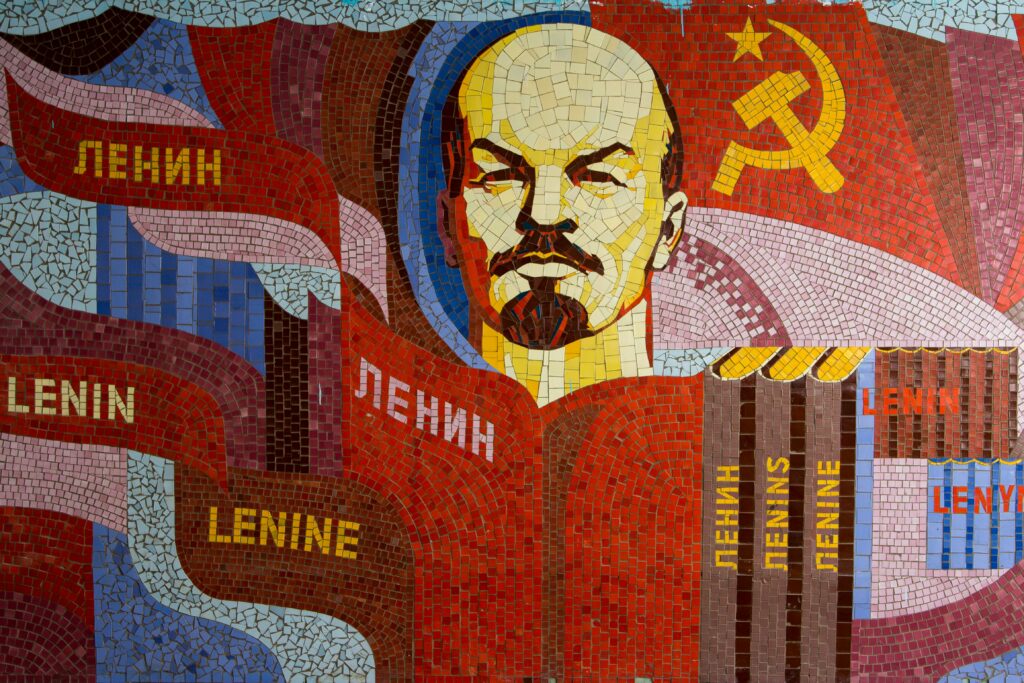

A Soviet-era mural depicting Vladimir Lenin in Kurchatov, Russia. Photo: Unsplash.

A Soviet-era mural depicting Vladimir Lenin in Kurchatov, Russia. Photo: Unsplash.

The Kremlin, Vosman stresses, is acutely aware of this fragility. Far from being detached from public sentiment, Moscow micromanages social moods at the most granular level, fearing loss of control above all. Its greatest concern lies ahead: the return of hundreds of thousands of men from the war – many radicalised, traumatised, armed and expecting rewards. Russia, with its poor healthcare system and limited social capacity, is ill-prepared for the wave of PTSD, alcoholism and unrest that may follow. The end of the war, Vosman predicts, will be deeply destabilising for the regime.

Nor does he believe that peace – or partial sanctions relief – would fundamentally improve Russia’s prospects. Any post-war euphoria would be short-lived. Economically, Russia is drifting towards dependency on China, reduced to a supplier of oil, gas and raw materials, with little capacity for innovation in a global economy increasingly shaped by AI, advanced technologies and scientific cooperation. Financial reserves are running low, oil price forecasts are unhelpful, and the long-term trajectory points downwards.

Not in Moscow’s strategic interest to destabilise the Baltic Sea

For Estonia and the Baltic region, Vosman offers a message of guarded reassurance. A conventional Russian military attack is unlikely in the near term, he argues. Moscow is tied down in Ukraine, takes NATO’s Article 5 seriously, and currently lacks intent to target the Baltics, which do not belong to Putin’s conception of “core Russia”. The real danger lies elsewhere: miscalculation, improvisation by overzealous subordinates, and hybrid actions that push boundaries without triggering full-scale war.

A security camera photo of Russian soldiers stuck in an elevator in Kherson, Ukraine, in 2022.

A security camera photo of Russian soldiers stuck in an elevator in Kherson, Ukraine, in 2022.

That same logic, Vosman says, applies to recent incidents involving damaged undersea cables in the Baltic Sea, including between Estonia and Finland. While suspicions of Russian intelligence involvement are understandable, he argues that it is not in Moscow’s strategic interest to destabilise the Baltic Sea, which is vital for Russian exports and links to Kaliningrad. Each incident fuels calls for tighter controls on the shadow fleet, expanded NATO missions and additional sanctions – “a mess Russia does not need”.

His assessment is that most cases are better explained by a convergence of risk factors: heavier Russia-bound shipping traffic, poorly maintained vessels, low professionalism among crews, expanding underwater infrastructure and heightened public scrutiny. Still, he cautions that “bardakk” – Russian disorder – means accidents and miscoordination cannot be ruled out, especially as long as the shadow fleet operates largely unchecked.

Confidence is a strategic asset

He is openly critical of alarmist claims that Russia is on the verge of attacking the Baltics. Such statements, he suggests, often conflate intent with capability, serve domestic political agendas, or are amplified by a media appetite for dramatic headlines. Intelligence assessments in Tallinn, Vosman says, broadly align with those of Estonia’s most capable partners.

On Ukraine, Vosman is sceptical of diplomatic breakthroughs. Vladimir Putin has not abandoned his core objective: restoring control over Ukraine as part of what he sees as Russia’s historical destiny alongside Belarus. Any agreement that leaves Ukraine weakened or partially occupied would amount to a pause, not peace. Yet there is a stark counterpoint: after years of war, Putin’s ultimate goal is no closer than it was in 2022.

US President Donald Trump welcomes Russian President Vladimir Putin to Joint Base Elmendorf–Richardson in Anchorage, Alaska, on 15 August 2025. The summit ended without agreement, as Trump implied that Ukraine should cede territory to end the war. Photo by Benjamin Applebaum / public domain.

US President Donald Trump welcomes Russian President Vladimir Putin to Joint Base Elmendorf–Richardson in Anchorage, Alaska, on 15 August 2025. The summit ended without agreement, as Trump implied that Ukraine should cede territory to end the war. Photo by Benjamin Applebaum / public domain.

Vosman also rejects the idea that NATO is on the verge of collapse or that the United States is preparing to abandon Europe. While Washington’s attention may wander, he argues that neither Congress nor any US president – including Donald Trump – would want to go down in history as the leader who rendered Article 5 meaningless. For all Europe’s anxieties and internal discord, sustained support for Ukraine has proven more resilient than many expected.

Estonia’s anxiety, he says, is understandable – but confidence is a strategic asset. “You have to believe in yourself, in your friends, and be ready to act,” Vosman concludes. Russia’s greatest strength may be intimidation, but its greatest weakness is fear – and the Kremlin knows it.