For over half a century, more than 150 plant specimens lay forgotten and tucked away inside a wooden cabinet in a Żabbar school library.

But now the scientific collection of pressed and dried plants, known as a herbarium, has been restored and recognised as a unique collection of mid-20th-century botanical knowledge.

The herbarium was painstakingly put together by students and teachers of St Margaret College (Primary B) between 1951 and 1952.

Details of the herbarium were provided in a recent scientific paper, ‘Flora Melitensis: A Natural History Gem from the Village of Żabbar, Malta’, by brothers and researchers Arnold and Jeffrey Sciberras. The paper was published this month in the Bulletin of the National Museum of Natural History, Malta.

“Coming across this herbarium was, for us, a window into the past, allowing me to study what existed in that area and understand what was happening there in the 1950s, since now most of the area is built,” Arnold Sciberras told Times of Malta.

The custom-built wooden cabinet, engraved with ‘Flora Melitensis’ in classical lettering, housed around 150 plant specimens mounted in 14 double-sided frames.

Coming across this herbarium was, for us, a window into the past

Not only a botanical archive, the herbarium also provides an important historical record of what is believed to be one of the island’s earliest documented attempts to integrate environmental education in Maltese schools.

Discovered inside school library

The collection was discovered in 2013 by the school headmaster at the time, Charlot Cassar, who was reorganising the school library when he came across the wooden cabinet.

He informed the Sciberras brothers of the discovery and they immediately began an intensive restoration process.

After decades of neglect, the herbarium was in a fragile state due to pest infestation and deteriorating materials. Thin plastic coverings, once intended for preservation, had decayed. The Sciberras brothers restored 72 specimens and replaced 40 others, sourcing replacements from wild and cultivated stock.

As a pest consultant, Arnold Sciberras said he felt it was “his duty” to conserve the cabinet because of its historical value and ensure it was pest-free for future generations.

“The most challenging part was conserving most of the deteriorated specimens and gathering the necessary data to understand what had occurred.”

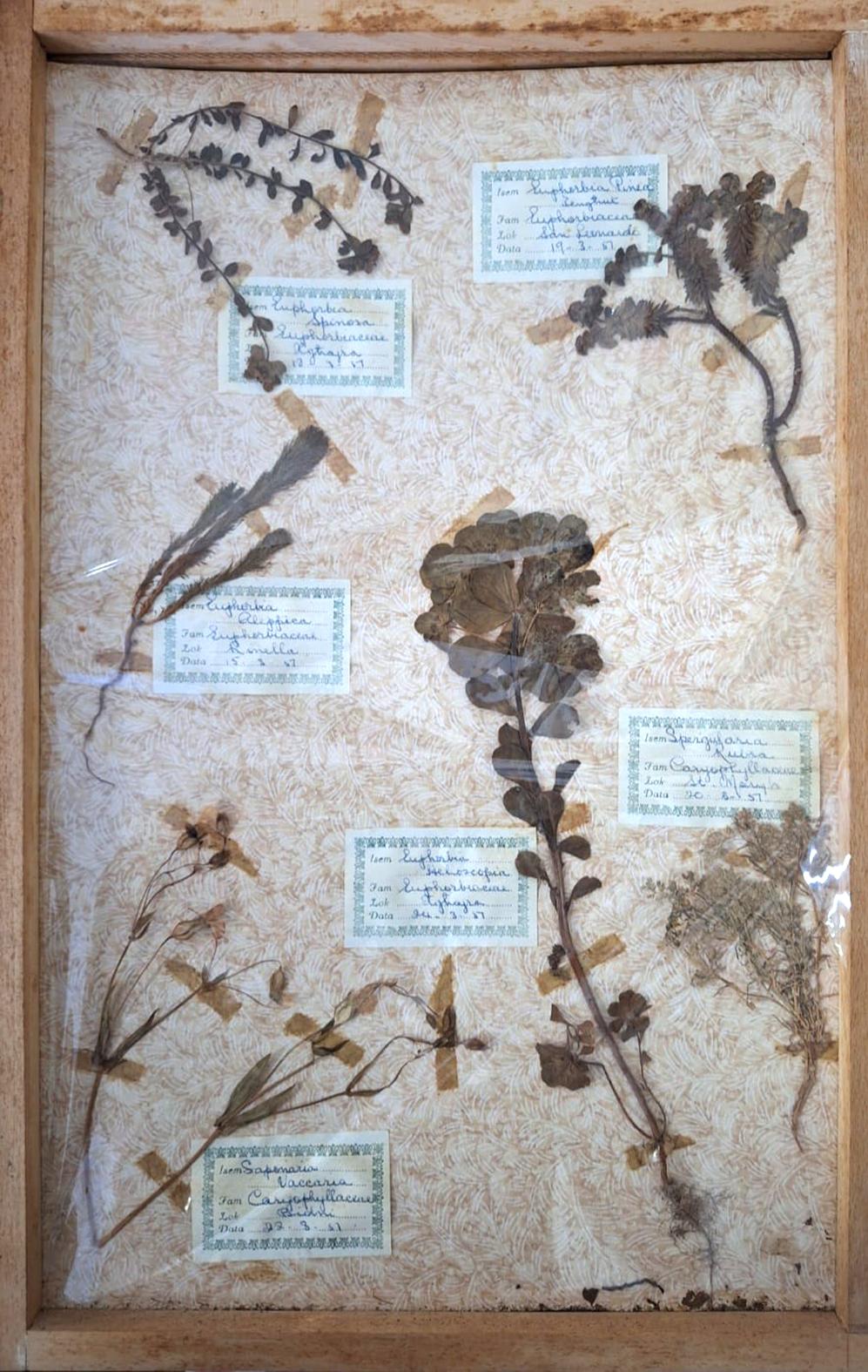

Example of the plant specimens framed in the herbarium cabinet.

Example of the plant specimens framed in the herbarium cabinet.The frames were cleaned and freeze-dried to eradicate any other pests in the specimens, labels and the frames. The cabinet was fumigated and thoroughly cleaned.

He explained how many of the plant specimens are still found locally, such as the small nettle (ħurrieq żgħir or urtica urens) and the Maltese star-thistle (centaurea melitensis).

The herbarium was part of the school’s project. Photographs showed students pressing and mounting plants on the display and also constructing the cabinet.

The school’s records revealed that the time the collection was created coincided with the tenure of the late headmaster Dominic Muscat. Further records highlighted how he undertook one of the school’s earliest initiatives to promote environmental conservation among students.

Documents showed Muscat offered different incentives to motivate student participation, including the opportunity for students to finish the school year earlier and the chance to win prizes for contributing to environmental conservation.

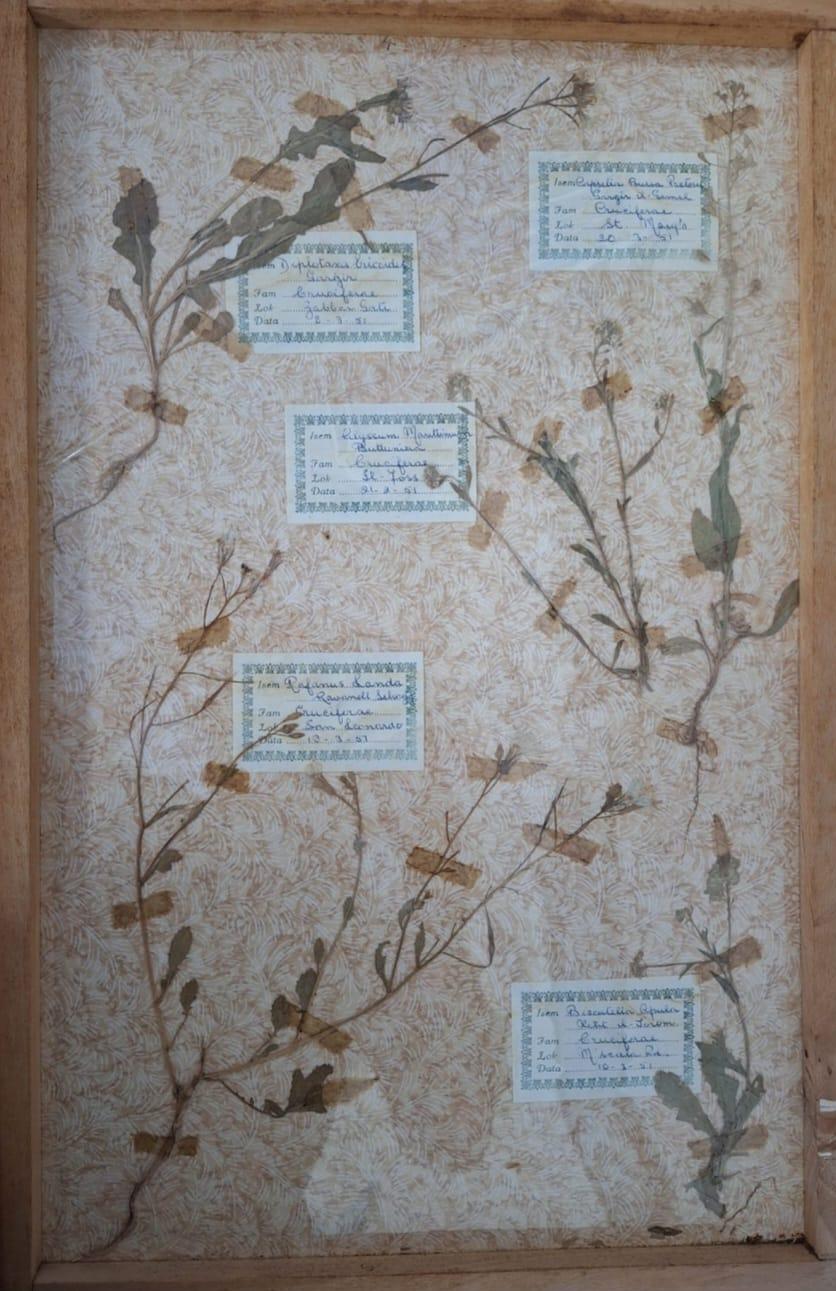

Another example of plant specimens found in the herbarium.

Another example of plant specimens found in the herbarium.Muscat drafted the cabinet design, drawing inspiration from the postal service display system. Paul Borg, in charge of the school workshop, built the cabinet and Joe Barbara, the science teacher, collected, displayed and labelled the flora.

Arnold Sciberras was lucky enough to interview one teacher, Carmelo Bonavia, in August 2013, months before he died.

Bonavia was the school’s history teacher during the time of the collection and explained how, at the time, environmental education was still in its infancy and its promotion was limited only to the efforts of the late naturalist, Anthony Valletta.

Bonavia said the school was the first government primary school in Malta to promote natural studies and also the first to have rooms dedicated to geology and natural history.

As the authors kept themselves busy researching and documenting the findings of the herbarium, the school’s current headmaster, Nicholas Agius, decided to donate the collection to them to further their research.

Once their study was completed in November, Flora Melitensis was donated to the National Museum of Natural History of Malta, in Mdina.

The herbarium is scheduled to undergo further treatment by Heritage Malta professionals before being added to the national collection.