The UK’s car- and London-centric transport policy undermines accessibility. It is pushing millions into effective poverty and entrenching transport emissions through forced car ownership. Will Edmonds argues that prioritising public transport, and equalising accessibility, would break Britain’s reliance on the car

UK society is addicted to the car. In 2023, 66% of journeys to work were by car, compared with 10% by rail and 7% by bus. In 2024, the transport sector contributed the highest proportion of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, at 30%. Decarbonisation efforts have resulted in a sharp fall in emissions from construction and energy supply. Emissions from private petrol vehicles, meanwhile, have only increased.

The UK’s transport system is unjust. At the individual level, car use isn’t a choice for many, but the consequence of a system that renders them reliant on cars to function. This leaves millions in effective poverty because they have no choice but to own a car. At a societal level, the impacts of accidents, noise and congestion fall predominantly on the poor.

I believe that a transport investment approach rooted in equality of opportunity can help solve our interrelated crises of climate and inequality. In particular, the government should reprioritise transport funding away from roads and trains towards buses and trams. An ambitious Labour government might consider tolls on major roads.

Outside London, you need a car to live a dignified life

Transport is important in enabling access to the things we need − jobs, shops, healthcare and education, among others. This concept of accessibility, defined broadly as the opportunity for people to access things, may be impacted by a journey’s time, cost, reliability and safety, for example. Greater accessibility to key needs brings improved employment, educational attainment and mental health. Equalising accessibility thus appears an important goal for a just society that seeks equality of opportunity.

Transport is an important pillar of equality of opportunity, by enabling access to things we need, including jobs, shops, healthcare and education

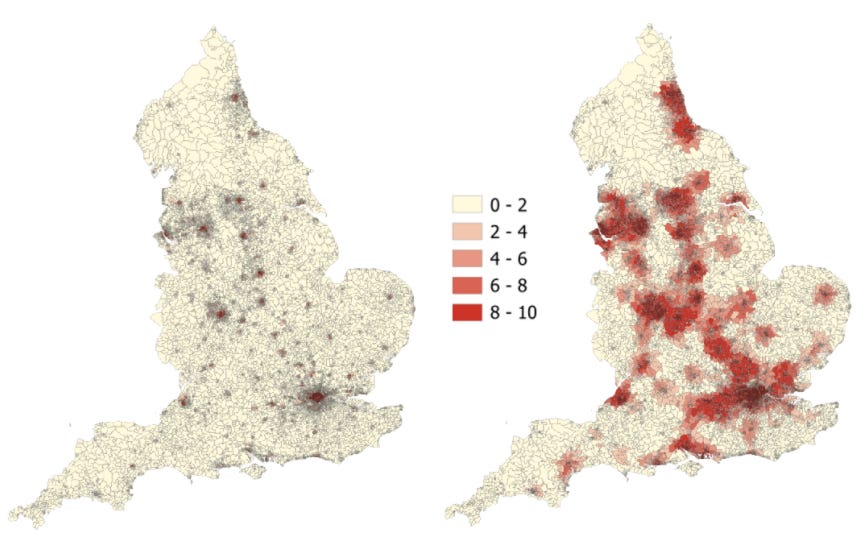

The maps below compare accessibility to employment opportunities across England, by public transport (left) and by car (right), using public data from the Department for Transport (DfT). Outside of the large cities, public transport is not sufficient to access work. In contrast, accessibility by car is far better. If you compared accessibility to groceries, GPs and primary schools, you’d find the same story.

This means that many in rural areas need cars to live a dignified life, at considerable cost, pushing millions into effective poverty.

Number of employment centres accessible by 30-minute journey by public transport (left) and car (right), 2017

UK transport policy entrenches inequality in accessibility

The UK’s transport policy approach, headed by the DfT, is apolitical. Based on a review of international transport policy approaches, Karel Martens’ excellent book argues that the DfT’s approach has predominantly focused on easing bottlenecks in an existing system. Investment has therefore been prioritised in large, congested systems such as roads, London’s railways, and the London Underground. Areas with little transport demand, meanwhile, are left by the wayside. Martens identifies similar approaches across other countries.

This approach may sound reasonable at first glance. But many in the UK don’t choose to forego journeys; they are unable to make them. Put simply: if there is no bus in Oldham, or if the bus is unreliable or expensive, people drive. The ‘bottleneck’, therefore, appears in roads, not public transport. This has led to investment in roads at the expense of public transport.

Many across the country don’t choose to forego journeys; they are simply unable to make them due to a lack of public transport

This bottleneck approach to transport policy therefore maintains the status quo in the UK. It has developed an entrenched car culture and a London-centric transport system. Although opportunity to travel is greatest in London, we continue to invest the most in London transport (£1,313 per capita, versus £693 nationally). We also invested £26.7bn in rail in 2024/25, the user base of which is predominantly richer and London-based. In contrast, buses and other local transport saw £4.7bn of investment, even though buses are the most commonly used mode of public transport, and are disproportionately used by disadvantaged groups.

Affordable, fast and safe public transport

The UK is increasingly implementing policies that promote an accessibility-based approach to transport policy. The Bus Services Act 2017 enabled regional mayors to regulate private bus services, setting schedules and routes to meet local needs rather than maximise profit. The Bus Services Act 2025 expands local powers to protect socially important routes and schedules. Another Bus Bill would secure regular bus services for all towns of over 10,000 people. The DfT’s new Connectivity Tool assesses national accessibility, demonstrating an interest in accessibility-based policy analysis. These are important measures to improve local public transport services, whose impacts will largely benefit the disadvantaged.

A focus on accessibility might re-prioritise investment from road and rail to buses, and away from London to the rest of the UK

What might this shift to an accessibility-centred policy mean for transport outcomes? The UK might re-prioritise investment from road and rail to local transport projects, and away from London to the rest of the UK. It may de-prioritise large, expensive projects such as HS2 (the UK’s ongoing high-speed rail project, costing £80bn) a third runway at Heathrow Airport (£49bn); and the capital envelope for major road expansions (£14.2bn since 2020). These funds could easily have been used to prevent the 50% rise in the National Bus Fare Cap, which increased the cost of single bus journeys from £2 to £3 (£350m); to extend bus fare concessions to targeted groups such as under-18s (in London, this costs £170m); or to expand bus schedules nationwide to allow people to travel home safely at all times of the day.

If the government wanted to avoid cancelling projects, it could raise money through road charging. Major road tolls were once commonplace in the UK but now, only one major road, the M6, is tolled. In contrast, 76% of France’s major roads are tolled, generating €11.6bn a year in revenue.

Riding towards transport equality

The UK’s entrenched car culture holds it back from a more socially and climate just transport system. A transport policy approach devised to address bottlenecks maintains this status quo, holding millions in effective poverty.

With a focus on accessibility, public transport could become the default mode of travel for most. Cars and vans would act as a necessary, but secondary, travel option. Millions in the UK could be lifted out of effective poverty, as car ownership becomes a choice rather than a need.

This way, we may begin to finally drive – no, ride – towards a more equal, climate friendly UK.